A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

In late January, Louisiana suspended its participation in a multi-state voter-roll-matching program known as ERIC, one week after rightwing conspiracy site Gateway Pundit baselessly accused ERIC of being “a left-wing voter registration drive disguised as voter roll clean up.” But if you ask Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin’s office, staff will tell you the decision had “nothing to do with” Gateway Pundit. What did the secretary base his decision on? The staff won’t say.

“We’re not having that dialogue,” said spokesman John Tobler, who said “numerous” experts had expressed concerns over “election stuff.” Who? “I am not at liberty to disclose that,” he said. What concerns? “We’re trying to get to the bottom of a major source of questions within the service provider” about “how the data moves and how it functions within their space,” said Tobler. What does that mean? Tobler won’t say, but he wants everyone to know “it’s not based on a conspiracy theory.”

In broad strokes, the Gateway Pundit story on ERIC — the Electronic Registration Information Center — asserts falsely that the organization is a front for lefty voter fraud funded by George Soros. That’s easily disproved. ERIC serves and is funded and overseen by its 30 member states, and employs a staff of three people. Those members are not “mostly blue states” as Gateway suggests, but a nearly even split. Soros has never given ERIC any funding.

Ardoin made the call unilaterally to suspend participation in ERIC on Jan. 27, saying in a press release the decision was made “amid concerns raised by citizens, government watchdog organizations and media reports.” The only media report was Gateway Pundit’s article. Tobler wouldn’t say who the watchdog organizations were, and I have seen no other public concerns expressed from watchdog groups about ERIC’s security or funding.

Ardoin had all of the tools at his disposal to fact check the Gateway Pundit article and the resulting stream of misinformed public complaints. ERIC’s bylaws say specifically that no non-member states are given access to the data, and also address how the organization is funded. Ardoin, I assume, has read the bylaws: The state enrolled in ERIC in 2014, while Ardoin was serving as first assistant secretary of state. And even if he hasn’t, Louisiana’s current commissioner of elections, Sherri Hadskey, serves on ERIC’s board, and her predecessor served as ERIC’s chair.

The day Ardoin sent out his press release, he’d had a 75-minute phone call with Shane Hamlin, ERIC’s executive director, aimed at addressing his concerns. Hamlin called it a “good discussion,” and said Ardoin asked questions about how the program manages personal voter data and its cybersecurity protocols, as well as the requirements of ERIC membership. Hamlin answered his questions, and Ardoin asked a few more about data security after the phone call. “We’re working through those now,” said Hamlin.

Tobler, the spokesman, wouldn’t tell me anything more about the questions, or whether Ardoin was satisfied by the answers he’d received so far. He ended our interview before we could go over how Louisiana planned to continue cleaning its voter roll in the same way as ERIC has allowed, and he did not respond to follow up emails. Since 2014, the program has sent updates to Louisiana to report:

- 16,330 deceased voters

- 54,600 voters who moved to another state

- 543,450 voters who moved within the state

- 4,260 in-state duplicate voter registrations

Given the volume of that valuable information, Ardoin’s decision to stop receiving it is striking. As NPR pointed out in its excellent coverage of Louisiana’s decision: “The far right is now running a disinformation campaign against one of the best tools that states have to detect and prevent voter fraud.” When states suspend their participation, it doesn’t just negatively impact their ability to clean their own voter rolls; it makes ERIC less effective for everyone. ERIC’s strength is in the sheer amount of data being shared among states, and removing Louisiana’s portion of that data makes it difficult to, for example, alert Texas if a registered voter in the Lone Star state moves to Louisiana and registers there. Or for other states to let Louisiana know if one of its voters has moved elsewhere and should be removed.

To counter the far-right misinformation, we’ll devote part of our newsletter over the next few weeks to providing the facts about ERIC and explaining the important role ERIC has had, as 30 states have widely acknowledged, in securing elections. We know the way to keep a lie about ERIC from spreading is to be first in educating voters with the truth so they know the lie when they see it. We encourage you to share this newsletter with people who express concerns about ERIC, and let us know if it helps.

In the meantime, if you’re a state or local elections administrator, we want to hear what you think about ERIC. Take this survey, and tell us about your experiences with the program and what impact it’s had on the state of your voter rolls.

Back Then

Most states did not have statewide voter rolls at all until after the passage of the Help America Vote Act of 2002, which required states to develop computerized and centralized lists. Many states had previously kept individual local lists rather than one statewide list and painstakingly (or, more often, poorly) coordinated between counties to clean them. HAVA also came with requirements to keep these lists up to date, and ERIC is used by its member states to adhere to this provision of the law.

In Other Voting News

- Thirty-three Democratic senators are calling for $5 billion in election security funding in Biden’s upcoming fiscal year 2023 budget proposal. This is half of what election administrators were all but promised last year, and an ask for money to be included in a future budget is hardly cash in hand.

- A new Politico Playbook poll shows that about half of Republicans are ready to move on from Trump’s claims of fraud in 2020, though that varies widely by how the question is phrased.

- Georgia Public Broadcasting is out with another edition of Battleground: Ballot Box — their invaluable podcast on elections and election policy — and it’s a helpful explainer on the importance of county voting boards.

- A new bill would breathe at least a small amount of air back into the lungs of a law in New Jersey requiring a paper trail for all voting machines. The requirement was supposed to go into effect in January 2009 but, like many things in elections, was never funded and, thus, never enforced. The bill proposed by two Democrats would require counties to replaces paperless machines with paper backed machines as they age out.

- Jim Condos, the Vermont secretary of state, has announced that he will retire after more than a decade in the job. He talked about his decision on WAMC.

- More evidence as to how heated state races are about to be: Liberal super-PAC American Bridge 21st Century will spend $10 million as part of its “Bridge to Democracy” program aimed at state races for positions with particular influence over elections, like secretaries of states, attorneys general, and county clerks.

And finally: The midterms are underway, y’all. At least they are in Texas, the first state in the nation this year to hold its primary. Here’s the most interesting news of the week:

- The week started with a lot of worry over returned mail-in ballots, rejected for the same reason all those applications were returned: They are missing identification numbers now required by state law, or the numbers are wrong.

- Hundreds of Republican voters followed the lieutenant governor campaign’s mailed instructions to send their ballot applications to the secretary of state, which has no ability to process them, instead of their county election office, which does. The SOS will now have to forward the mail on, delaying those applications by several days. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick says he encouraged this route because he thinks his voters don’t trust Democratic county officials.

- The Texas Tribune has a deeply-reported piece on the worry some Texans with disabilities are feeling over the limited level of assistance they can receive at the polls under the state’s ambiguous new law.

- KXAN in Austin is keeping track of turnout.

Infographic of the Week

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

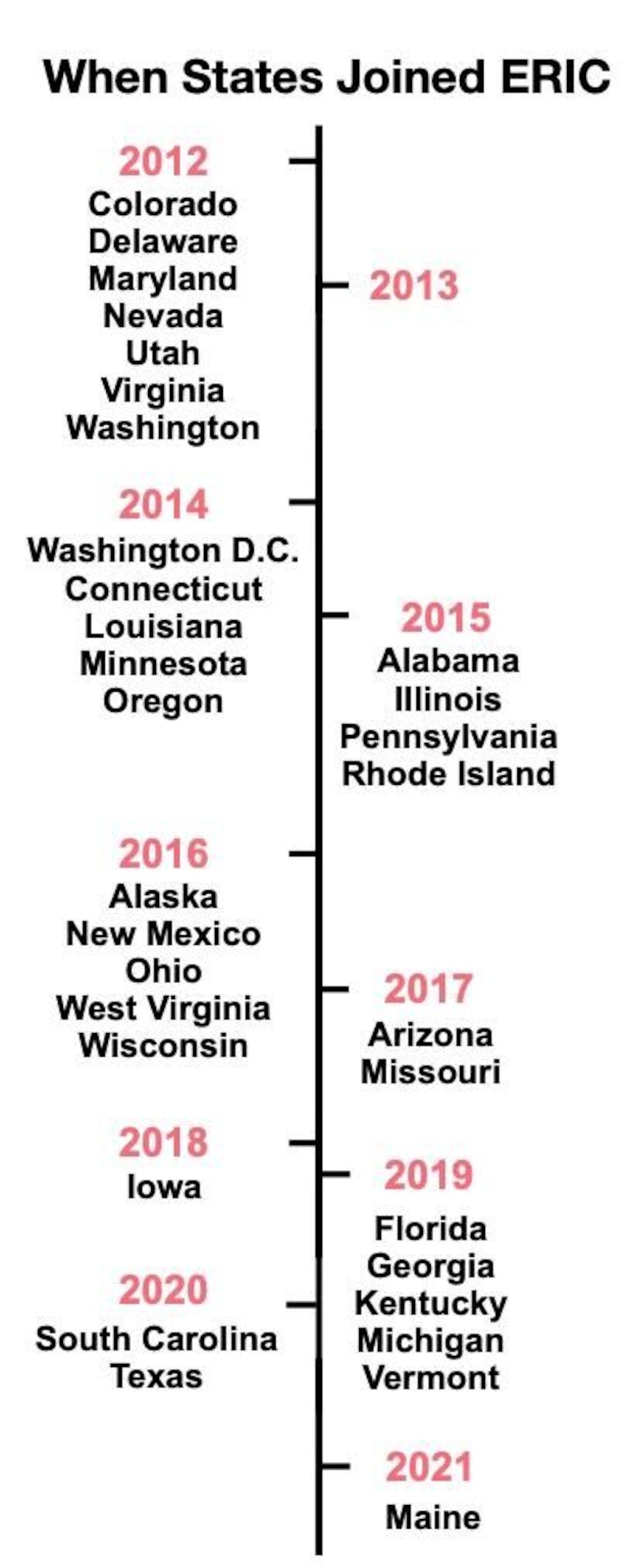

This year-by-year timeline I created shows the pace at which ERIC’s member states joined the program, and the mix of states that joined each year.