A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

Let’s talk about rejection. Specifically, absentee ballot application rejections in Texas. We hate to say We told you so to the legislature, but we did warn that this problem would come up.

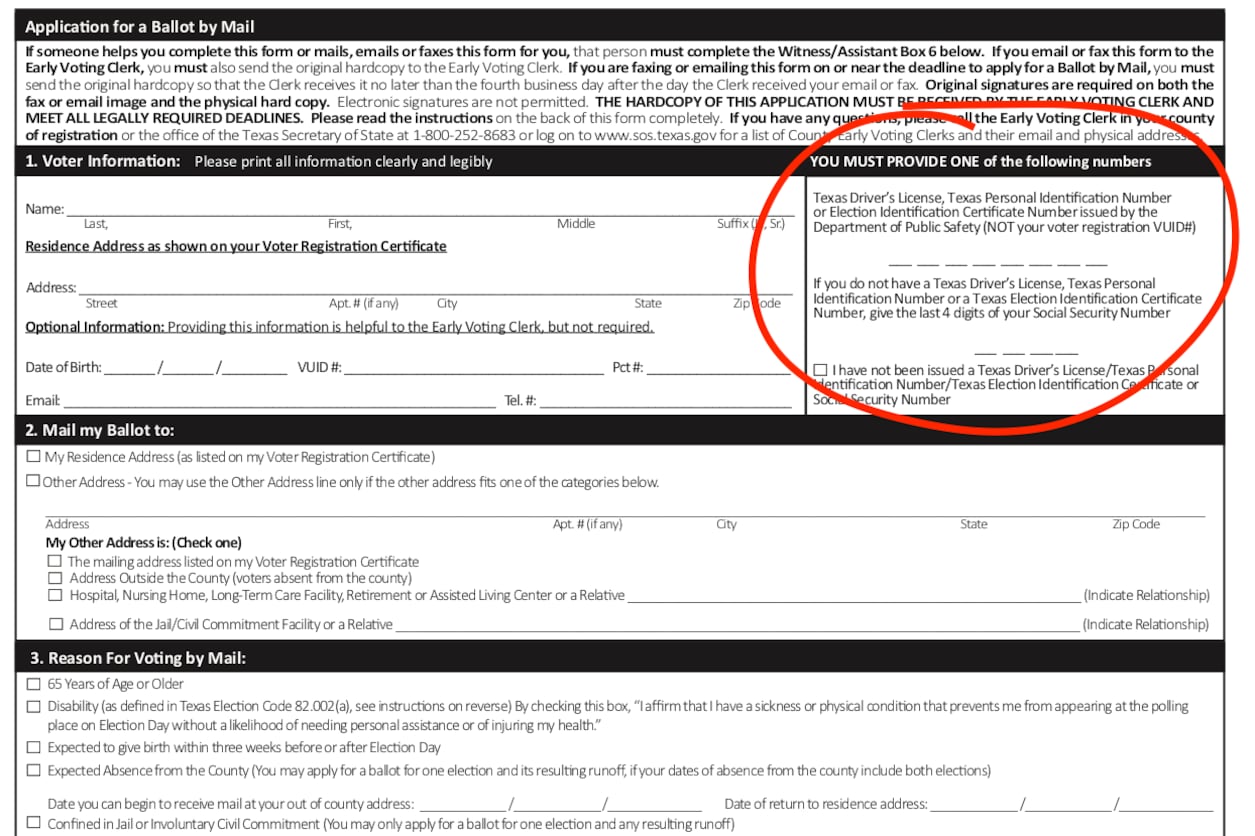

When Texas passed its long, winding voting bill in its second special session last year, it changed the way absentee ballot applications work. Now, voters must provide either their driver’s license number or partial Social Security number (federal law does not allow states to ask for both), and the law requires that number to be checked against the number on file with the voter registration office. There are a number of problems here that — without effective technology and appropriate voter education — will trip folks up:

- If the forms are ineffectively designed, or voters aren’t appropriately notified, they could leave these numbers off altogether.

- Hundreds of thousands of voters are missing their Social Security number or their driver’s license number in the voter registration system. If they were to write the incorrect number on their application, they’d be rejected for a mismatch even though they are the same person. When we reported on the problem last summer, the total number of voters missing one or the other was 1.9 million, though the secretary of state’s office has since been attempting to bring that total down by filling in the missing data.

- The state and counties offered inconsistent guidance on what to do if applicants submitted an old form for an absentee ballot. Many counties that received applications printed before the new law had to reject these applications, because the old form doesn’t require or provide a space for the voter’s ID number. (Here’s the new form.)

- The state’s cure process for all of these problems is confusing.

You might assume that after the regular legislative session and multiple special sessions, the bill would have had enough baking time that lawmakers would have solved these obvious problems. They did not — even after these problems were raised by county clerks and our reporting. And so over the last several weeks, large counties across Texas have reported rejecting hundreds of absentee ballot applications due to the above reasons. This, I repeat, was avoidable.

According to numbers reported this week by the Wall Street Journal, Harris County has rejected 35 percent of all absentee ballot applications due to the new rule. Travis County rejected 27 percent, and Bexar County rejected 28 percent, with clerks in both counties attributing a large percentage of the rejections to confusion over the new law. It is difficult to be more specific given current figures. These rejections could have affected voters who wrote the wrong number on accident, who have an incorrect number listed in their registration record, who are among the voters missing one of the numbers in their registration file, or who didn’t provide a number.

Just as in 2016 when the state enacted its voter ID law, the counties and the secretary of state’s office are in disagreement over whose responsibility such preparations were — and voters have been stuck paying the price. No real solutions have so far emerged, but Travis County and the SOS office are taking slaps at each other on Twitter, which I guess is entertaining but not really helpful to voters.

Any time a law changes and officials don’t dedicate enough time and resources for appropriate preparations, voters will be the ones left holding the bag. The law was written by legislators with poor understanding of the mechanics of voter registration and without consulting elections administrators about the potential consequences. With only a few short months after the law went into effect — a period punctuated by the holiday season — the state and counties simply did not have the capacity to divine meaning from the confusing legislation and make appropriate changes.

Imagine, alternatively, this entire application process taking place online, as it does in 18 states. In this ideal world, the form is secure and won’t let you submit your information unless the application includes your ID number, which even a modestly sophisticated system could verify. If it doesn’t match, the system could tell you, allowing you to instantly address errors. In theory, this would reduce rejections to nearly zero. Even though Texas has an online portal (albeit a confusing one) for curing ballot rejections and application rejections, you are still barred from submitting the actual application online. It’s a barrier that makes little sense, and it’s one that’s been erected by legislators who don’t understand the mechanics of the system they claim to protect.

Given the intense focus on changing voting laws across the country, this is a show I’m sure we’ll see reruns of. Texas, however, gets a bit of a reprieve. Its legislature won’t reconvene until next year.

Back Then

Voter registrations weren’t really even a thing until the 1800s, when a wave of anxiety about voting by transient people swept the country and when legislatures began to enact residency requirements. These came with clerks who maintained a centralized roster and often had unilateral authority to remove people from the rolls. Massachusetts created its registration system in 1801, South Carolina instituted one only for the city of Columbia in 1819, and a smattering of other states and localities followed. Still, most states did not have any such system until the middle of the century, when the Whig Party gained power and anti-immigrant sentiment took hold.

In Other Voting News

- Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski is among the moderates calling for compromise on voting rights legislation after Democrats’ most recent failure this week to advance their bills. “I think that we need to do everything that we possibly can to avoid further polarizing voting rights and election reforms,” she said. “It may be just too late, but I think we have to try.” One option for such a compromise was presented this week by the Bipartisan Policy Center, Issue One, Unite America, the R Street, and the American Enterprise Institute in their joint report, “Prioritizing Achievable Federal Election Reform.” Rather than demand specific reforms through statute, they recommend issuing grants to states across a set of policy areas to encourage election advancements.

- Beep ... beep ... beep. What’s that noise? It’s the sound of Joe Biden backing up on comments he made in a press conference this week. He said future elections “could easily be …illegitimate” if the Democrats’ favored voting bills do not pass. Press secretary Jen Psaki said on Twitter and at a press conference that Biden was referring instead to the prospect of states following through on former President Donald Trump’s demands to subvert the election.

- Republicans in at least three states are proposing what amount to voter fraud police, even though instances of voter fraud are, and have always been, minuscule. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s plan would include 20 officers spread out across the state. Arizona State Sen. Wendy Rogers has submitted legislation for a “bureau of elections” inside of the governor’s office with a range of investigative powers, and Georgia gubernatorial candidate David Perdue wants a dedicated state police unit.

- Meanwhile in Georgia, the prosecutor in Fulton County has requested a special grand jury to assist in her investigation of Donald Trump’s infamous phone call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger last January. The prosecutor, District Attorney Fani Willis, told the judge in a letter that multiple witnesses have declined to cooperate without a subpoena.

- The state of Idaho is demanding that MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell take down false information on his website claiming there was voter fraud in the state. The secretary of state and attorney general issued Lindell a cease and desist letter demanding the information be removed, and requested $6,000 for the state’s costs of disproving his false claims.

- A bill that would continue absentee ballot availability for individuals at risk of COVID-19 advanced in the New York Assembly this week. “It is unconscionable to force New Yorkers to choose between their health and their vote,” said Assemblyman Jeff Dinowitz, sponsor of the bill.

- A man who encouraged his social media followers to “prepare for war” after the 2020 election will now be an election judge in Hudson, Wisconsin. The man, John Kraft, was forced to step down as chair of the local St. Croix County Republican Party after his comments on Facebook last year. A city council member who raised objections to Kraft serving in the role formally apologized for her objection after being threatened with censure.

In Case You Missed It

This week I participated in a panel discussion with Margaret Sullivan of the Washington Post and Barton Gellman of The Atlantic, led by UCI law professor Rick Hasen. The discussion will be posted on the Fair Elections and Free Speech Center’s website in the coming days. It was a fantastic discussion (thanks, Rick!) and, if you can believe it, we all agreed on a few things: Journalists cover elections best when they focus on local stories of demonstrable impact to voters. Journalists should be more aggressively reporting on issues of democracy and election integrity, and can do that only if they more deeply understand election systems. And, things aren’t looking great when it comes to voter confidence. The media can help. We’re excited to do all of those things at Votebeat, and hope you’ll help us spread the news that we have five (5!) jobs listed on our site.