A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

The Supreme Court decided last week that Alabama can conduct its 2022 congressional elections under a map that a lower federal court ruled was racially gerrymandered. The justices, in a 5–4 decision, allowed the map to be applied to this year’s midterms, determining that it was too close to the election to force changes to the map.

That’s not a very satisfying argument for the plaintiffs. In oral arguments, both Democrats and Republicans acknowledged that the plan was rushed given the delay in the release of population numbers from the Census Bureau. Alabama sued to get the data released sooner but ultimately wasn’t successful, pushing the finalization of the maps to the last possible moment allowed by the state’s Constitution. The governor signed off on the maps in late November after six days of consideration by the legislature, and the plaintiffs sued the very next day. Still, five of the Supreme Court’s conservatives ruled that the lower court’s decision on Jan. 24 would have forced changes to the map too close to the state’s primary, which is scheduled for late May.

The upshot of this is clear: If the Supreme Court has determined that the challengers cannot bring their case the day following the approval of the maps, then it is impossible to give any relief to minority populations who are discriminated against in redistricting. It would have been functionally impossible for the plaintiffs to bring the case sooner, meaning the Alabama legislature is being given a free pass on what the facts show is blatant discrimination. The lower court’s unanimous panel of three judges (two of whom were appointed by President Donald Trump) ruled that the maps unlawfully discriminated against Black voters by drawing only one majority-Black district, when there should have been two or, at minimum, a second district with a large number of Black voters. And that justification is not hard to see: While Census numbers clearly indicated that the minority population of the state rose while the white population of the state dropped, the number of minority opportunity districts (totaling one out of seven — despite a quarter of the state’s population being Black) was unchanged from the previous map passed after the 2010 Census.

The 7th District, encompassing the area around Birmingham and most of the state’s western Black Belt, holds the vast majority of the state’s Black voters. Plaintiffs argued that the map made it near impossible for Black voters to meaningfully participate if they live outside the district. Per the Montgomery Advertiser, the plaintiffs advocate the creation of “a 7th congressional district that would be 47% white and 45% Black, and a 6th congressional district that would be 51% white and 41% Black.”

The Supreme Court’s order last week was not a ruling on the merits of the case. The decision does not say that the map does not discriminate against Black voters, but instead puts the lower court’s decision to overturn the map on hold until the matter can be fully argued before SCOTUS. But, given the passage of time before those arguments can commence, the legislature’s map will be in effect during the midterms.

The decision was made as part of the court’s “shadow docket” — decisions made by the court without oral argument and largely without explanation by the justices. Still, Justice Brett Kavanaugh chose to explain his reasoning. “In short, the Purcell principle requires that we stay the District Court’s injunction with respect to the 2022 elections,” he wrote. “The Court has recognized that ‘practical considerations sometimes require courts to allow elections to proceed despite pending legal challenges.’ So it is here. If the District Court’s judgment is eventually affirmed after appellate review, the injunction can take effect for congressional elections that occur after 2022.”

Essentially: The shadow docket is being used to give the legislature a get-out-of-jail-free card for the first year of an election cycle. The year reflects a perfect storm of delay, making the Purcell Doctrine even less useful. Under the Trump administration, the pandemic-triggered census data delays exacerbated previous delays caused by the administration’s unprecedented intervention in the survey, forcing a lag in the delivery of results to state legislatures by several months. This compressed an already quite speedy timeline: The Alabama legislature passed the maps after a few days of deliberation, and they were signed by the governor almost immediately. The plaintiffs sued the very next day, and the conservative justices have still said it was too late. It’s difficult to see how any challenges to maps could be successful with this set of justices, regardless of how plain the damage. Now consider that Alabama is far from the only state facing a contested map.

“It’s impossible not to conclude that what we see at work is not some neutral principle guiding the Supreme Court’s intervention but simply whether a majority likes or doesn’t like what a lower court has done,” writes Linda Greenhouse in the New York Times. “The election is months away — plenty of time for the legislature to comply with the decision.”

We saw states move far more nimbly in 2020 to respond to challenges brought by the pandemic. States, it’s worth noting, clearly have the ability to delay elections in order to accommodate these necessary shifts. They did it in 2020, and certainly could do so again this year given enough political appetite and judicial enforcement. Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court just last week put a hold on the state’s election calendar to accommodate redistricting issues. If state legislatures and state executives refuse to take these steps, the courts can force them to.

This is an inauspicious start to voting rights litigation in 2022, and is likely to impact the rest of the court’s decisions on redistricting. “Five members of the court appear to be valuing an alleged administrative burden on states to redraw district lines that comply with federal law more than they value minority voting rights,” writes Loyola law professor Jessica Levinson of MSNBC. “This could give every state one free pass at a voting rights violation, as long as they wait long enough to impose them.”

Back Then

In the late 1860s, after the passage of the Reconstruction Act, conservatives in Alabama sent a letter to Congress decrying the possibility that Blacks and impoverished whites would band together, and denouncing the enfranchisement of “negroes.” They wrote that Black voters were “in the main,” ignorant of the principles of free government and “disinclined to work, credulous yet suspicious, dishonest, untruthful, incapable of self-restraint, and easily impelled…into folly and crime.” In the early 1900s, Alabama caught on to the wave of other states re-popularizing the notion that voting was only for some, not all. In 1901, in ratifying the state’s sixth Constitution, the state’s legislature altered the preamble to reflect that suffrage was a “privilege,” not a right. The previous Constitution had banned both property and education requirements as qualifications to the ballot.

In Other Voting News

- Miles Parks is out with a fulsome explainer on the bizarre new right-wing obsession with the Electronic Registration and Information Center — a nonprofit data matching service that helps states clean their voter rolls. While you’d assume Republicans would be all about keeping voter rolls clean, there is a new movement spurred by misinformation to pressure states to abandon the most widely praised, commonly used tool for doing just that. Read about it here.

- The U.S House approved a major overhaul of the United States Postal Service, approving the measure 342–92. Its companion bill in the Senate has bipartisan support and is expected to pass as well. Most notably, it removes a mandate that the USPS cover healthcare costs decades in advance, which has sent the carrier into a financial tailspin since its passage in 2006.

- One of the final counties in Texas to use paperless voting machines has opted to replace them ahead of the 2022 November midterm. Jefferson County leaders technically have until 2026 to make the move, given a vote by last year’s state legislature, but have decided to move forward with purchasing the machines this year. Peoria County, Illinois, has made a similar move. Hidalgo County in South Texas is retrofitting its machines.

- Are ballot drop boxes legal in Wisconsin or not? It depends on which election is in question. The Wisconsin Supreme Court last week affirmed a lower court’s ban on ballot drop boxes for the April 5 judicial elections. The court had previously ordered, however, that the boxes may be used in this month’s local primaries. The court will decide the fate of drop boxes when it hears arguments in the case later this year.

- Massachusetts’ top election administrator has criticized the governor’s new budget for “dramatically” underfunding elections. Secretary of State William Galvin has asked the legislature to include millions more dollars so that the state can hire staff to implement new maps and educate voters about dramatic voter reforms and statewide elections this year.

- Two American Indian tribes have sued the state of North Dakota over its new legislative maps, alleging that they dilute the voting power of their tribal members. The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and the Spirit Lake Tribe have filed suit against North Dakota Secretary of State Al Jaeger, alleging violations of the Voting Rights Act.

- Tina Peters is at it again in Colorado, where she was arrested Tuesday after refusing to comply with a search warrant. The Mesa County Clerk is already under investigation for allegedly making unauthorized copies of and distributing secure election information. The warrant was for Peters’ iPad, as she was being investigated for allegedly filming a Monday court proceeding related to the case. Meanwhile, the state has adopted temporary new election security rules in reaction to allegedly mishandled data in county election offices.

- Here’s a weird story from the Washington Post on a strange voter fraud conspiracy out of Otero County, New Mexico.

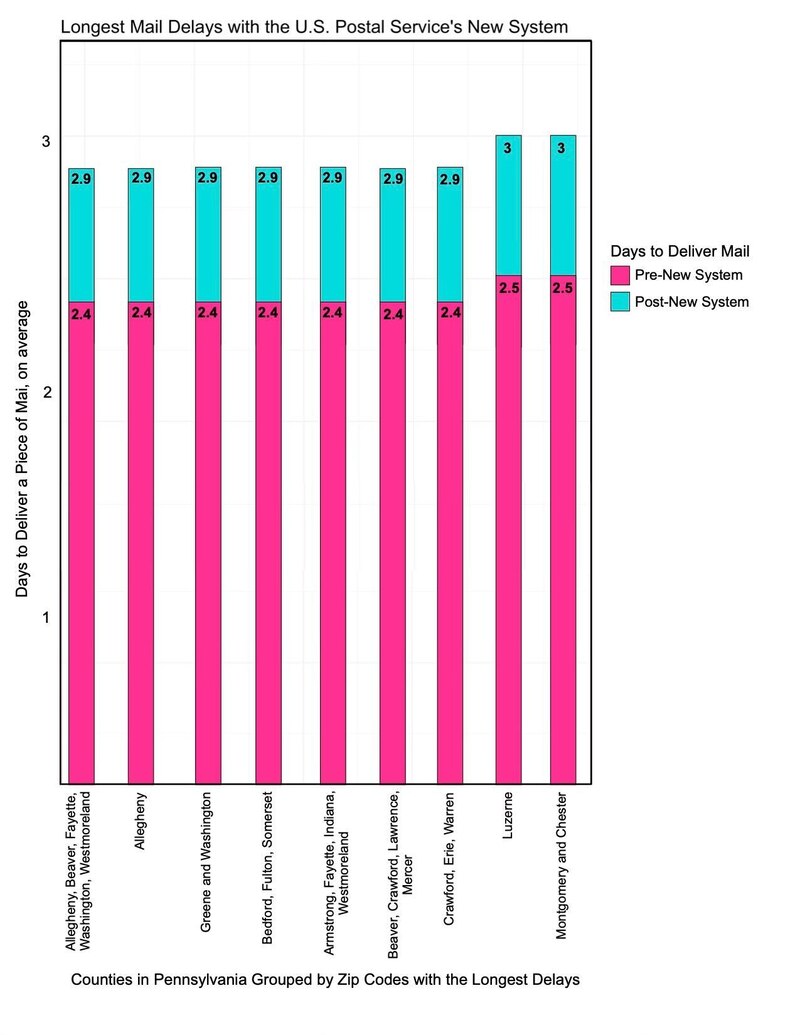

Infographic of the Week

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

It turns out that I need an original copy of my birth certificate to show to UPenn for this fellowship, but I didn’t know that when I left my home in South Florida. So, I asked my mom to mail me a copy. After nine days, it still hasn’t arrived. It struck me that I’m not the only person struggling with mail delays — and the consequences for the election are far greater than my delay in completing on-boarding paperwork. So, this week’s infographic: Mail delays in Pennsylvania, which could make the state’s redistricting process an even bigger headache.

In October, USPS implemented a new system that was supposed to cut costs and create more consistency in transportation schedules. But, it led to mail delays across the country instead. Below is a graph detailing the Zip codes with the longest mail delays in Pennsylvania, indicating how long it took to deliver a piece of mail, on average, before and after the new system. Montgomery and Chester counties, for example, have been experiencing some of the longest delays (mail previously took an average of 2.5 days to reach these counties and is now taking 3 days). While the longest increase in average delivery time was only half a day, the new system may cause longer delays if millions of ballots are mailed out across the state at the last minute.