A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

We’re back to exploring the truth about the Electronic Registration Information Center and explaining the important role ERIC has in securing elections. First we looked at why Louisiana seems to have suspended its participation in the voter-roll-matching program, then we took stock of the value other states — red and blue — have found in the program without harboring any similar suspicions.

Now I want to lay out the implications when states remove themselves from ERIC. In summary: It hurts the state itself, but it also hurts every other state in the program — especially the neighbors of the state in question.

Let’s first talk about data. ERIC is, to put it simply, a program that matches one state’s data with another state’s data to see if the same person is on two voter rolls, has moved across state lines, might be dead, or has undergone a number of other changes. In Louisiana alone since 2014, ERIC has identified 54,600 people who have moved out of state and 16,300 deceased voters. When you have more data to match against, you get more matches, so these numbers go up. This, folks, is just how it goes. It’s math. Thus, the reverse is also true: When there is less data, you get fewer matches and the program is not as robust. Makes sense, right?

When you have more data, you get more matches, so the number of flagged voters goes up. It’s math.

So, sure, Louisiana’s voter-roll accuracy is suffering the most from its (hopefully temporary) hiatus from this program, but everyone else is also a little bit worse off for not being able to match their voter roll against that state’s. Texas, the only ERIC member state that borders Louisiana, suffers more than every other state, because we have long known that while in-state moving is the most likely reason for a person’s voter registration to be inaccurate, the next most common reason is picking up and putting down in a bordering state. If any of the folks who commute from East Texas to Shreveport, Louisiana, decide to move to be closer to work, neither state will be aware of that change. Texas and Louisiana are also constantly trading residents because of the intensifying hurricanes on the Gulf Coast, and Louisiana’s withdrawal removes a key way both states would make those adjustments. As many as 250,000 people relocated to the Houston area from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, for example.

Louisiana is the very first state to ever step away from ERIC, and we’ve demonstrated that the decision appears to have been based on conspiracy and rumor. While that’s bad for the citizens of Louisiana, elections officials in every other member state are decidedly not thrilled about this. So far, no other state has contacted ERIC with similar concerns, but they have expressed their frustration about Louisiana’s pullout.

Shane Hamlin, the executive director of ERIC, says that while the way the matches are done will not improve or worsen because of the addition or subtraction of any given state, “the more states that are in, the more cross state movers we can identify.” This has been a huge selling point for the program, and specifically helps ERIC recruit states whose border neighbors are members. “It improves ERIC’s value,” he said.

If you’re a state or local elections administrator, we want to hear what you think about ERIC. Take this survey, and tell us about your experiences with the program and what impact it’s had on the health of your voter rolls. We’ll keep covering this.

Back Then

As urbanization took hold in the late 1700s, lots of voters who were once eligible to vote by virtue of being farmers or property holders suddenly found themselves no longer eligible after giving up their agrarian lifestyle and moving to the cities, where they rented homes or apartments, for better quality of life or higher wages. In Northern Louisiana, as parishes were formally established in the early 1800s — such as Bossier and Caddo — white males found themselves newly disenfranchised at high rates. (We don’t know exactly how high, though, because number keeping back then wasn’t exactly awesome.) White men in North Carolina and Virginia saw similar disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, in the North the popularity of farming was increasing. But in places like New York, where farmers purchased land through installment mortgages, there was not the reverse effect. New York did not consider a voter to be eligible unless all mortgage installments had been successfully paid.

In Other Voting News

- The Brennan Center is out with a new survey that shows that one in five election administrators are considering leaving their jobs before 2024 — a terrifying thing to read but probably not that surprising. With voters screaming at election administrators over conspiracy theories and sending threatening messages to their offices, and with legislatures considering laws that require extensive time and effort from election officials, one can imagine the exasperation of continuing in this work.

- Making it harder is the lack of concern federal lawmakers show for our crumbling election infrastructure. In the gigantic budget approved last week, Congress apportioned only $75 million in election funding to be shared among all states. That averages to $1.5 million per state. For a comparison, a single county in Nevada recently budgeted $1.3 million just for printing and temporary staff for the midterm elections.

- A bang-up analysis by the Associated Press has found that Texas flagged 27,000 mail ballots for rejection in its recent primary — a rate that far surpasses past elections — largely due to the state’s new election law. What part, largely? The part we told you about last summer.

- Republicans in the Arizona Senate passed several new provisions to the state’s election code, but one Republican senator appears to be integral to mitigating the most severe proposals. “I’m a firm no — if it’s bad policy I’m not horse trading,” Sen. Paul Boyer told the Associated Press after being the determinative vote in defeating three Republican-backed bills.

- The Pennsylvania Supreme Court heard arguments over the state’s vote by mail law, Act 77, which was initially passed in a bipartisan manner in 2019 and hailed as a leap forward for voters. Eleven Republicans who voted for the law are now arguing against it in court, claiming that the state Constitution doesn’t actually give them the power to make such a change to mail-in voting.

- The Tina Peters drama continues in Colorado. The Mesa County clerk was indicted on seven felony charges and three misdemeanors. Her deputy, Belinda Knisley, was indicted on six counts. All counts are related to election tampering and official misconduct.

- Reporting by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel shows that Michael Gableman — the former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice who was leading a $676 million investigation into the state’s 2020 election on behalf of Republicans — wasn’t doing as much as Republicans implied. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos said earlier this year that he had served more than 100 subpoenas — he hadn’t. Copies of only 86 subpoenas were provided to the legislature, and almost all subpoenas that were written to out-of-state entities were never served, including one meant for the Center for Tech and Civic Life and another meant for the Vote at Home Institute.

- The Connecticut legislature’s Government Administration and Election Committee recommended extending modifications to the state’s absentee voting laws that were made to accommodate pandemic voting, allowing all voters to cast a ballot by mail, not just those suffering from illness.

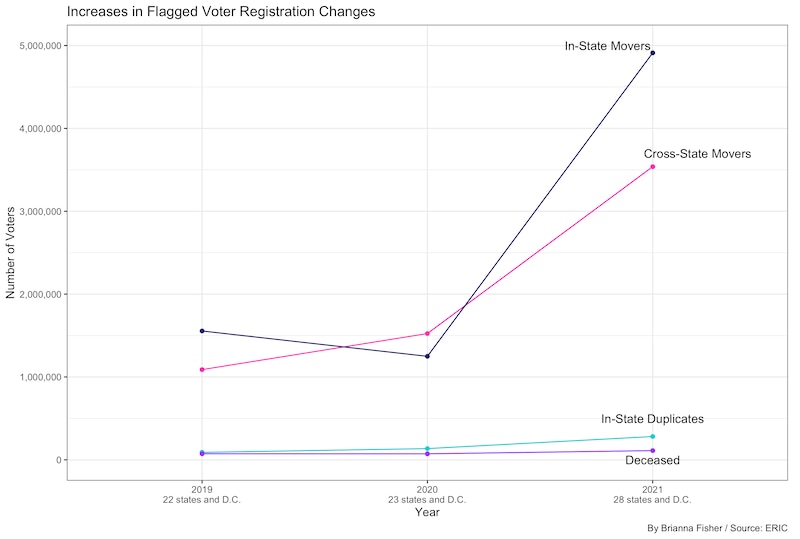

Infographic of the Week

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

Hi everyone. This week, I want to take a look specifically at in-state voter movement identified by ERIC. While states have their own methods for identifying these voters — online voter registration, for example, has hugely improved states’ ability to find them— this is the most common type of record flagged by ERIC and accounts for most of the data provided to states.

You’ll see a massive jump in the number of in-state movers from 2020 to 2021. There are a few possible reasons. Texas and Florida — both gigantic states — joined just before that period, making the total number of voters whose registrations are examined in ERIC shoot up significantly. There are about 30 million registered voters across both states. Florida’s high number of flagged records, however, is a bit surprising given that the state implemented online voter registration in 2017, which generally results in voters more proactively reporting address changes. (This is the lowest lift for voters to update their address, which means they actually tend to do it, and also means that states tend to have more robust movement data than states that don’t have online voter registration.) Also, people just moved a lot in 2020 as the pandemic upended lives all over. Mass, unpredictable changes like this demonstrate the need for robust voter-roll matching. While ERIC isn’t capable of figuring out why someone moved or why they are on two rolls, it can simply highlight the fact of it for states and counties to handle as state law requires.