A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

We’re bringing our series about the Electronic Registration Information Center to a close. Recall that this all started because of a conspiracy theory in far-right media baselessly alleging that ERIC was a liberal voter-fraud plot. The truth, as we’ve shown, is that ERIC works to prevent fraud and does so better when more states participate. Another rebuttal to this conspiracy theory is that ERIC provides no advantage to Democrats, just as it provides no advantage to Republicans. ERIC simply benefits elections — for both parties. Given that the right is concerned about election security and the left is concerned about fairness in voting access, the attraction of ERIC is that it achieves both.

A recap of what the program is: a standardized voter-roll-matching service that gives all states the same type information in the exact same way, all aimed at removing ineligible voters from the rolls and ensuring that voters who should be on the rolls are registered at the correct address.

I’ll highlight something Justin Levitt, the White House’s senior voting rights policy adviser, said when I joined him on the Civics 101 podcast this week: “You’ll generally find that where you can have increased security without the tradeoff for access or other things that we like, that there is pretty uniform support for having that security,” he said.

ERIC is one of those things — a best practice that most election officials, regardless of political leanings, are enthusiastic about and supportive of, which is why it was so surprising when Louisiana suspended its participation.

Conservative secretaries of state have hailed ERIC as a way to keep voter rolls clean and free of bloat that can (and only very occasionally does) lead to fraud or mistakenly cast ballots. This can lead to a lot of nail-biting when it comes to local races with tight margins. ERIC also clears dead people from the rolls (though votes cast by dead people are incredibly rare), and prevents people from casting ballots in two states (this doesn’t happen very much either).

The left says it’s worried about disenfranchisement caused by aggressive and targeted voter roll maintenance. That’s not an unfounded concern — Texas, for example, attempted in 2019 to remove thousands of people who Attorney General Ken Paxton claimed were non-citizens from the roll, though most turned out to be legally registered. And a list maintenance process Ohio attempted to do in 2019 using its own data revealed a mess of improperly flagged voters — fortunately before any were removed. ERIC helps here, too.

“Removal of records from the list isn’t inherently bad or good,” said David Becker, the director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, who helped create ERIC when he worked at Pew. “Removing records of those who are no longer eligible to vote in the state or have moved is good. Removing records of people who are eligible is bad. ERIC helps make sure that only the appropriate registrations are removed.”

ERIC’s standardized roll-checking ensures that member states are largely doing this maintenance in the same way. Texas receives a report from ERIC based on the same standards that Washington state and Oregon do, making it harder for Texas officials, like Paxton or the growing number of Republicans advocating extreme positions, to call for aggressive list maintenance activity that could, truly, hurt voters as it has done in the past.

The kind of roll maintenance ERIC does also allows states and counties to appropriately allocate resources. If the voter roll is an accurate reflection of where voters should be registered given their address, a county can deploy its limited resources appropriately. Neighborhoods aren’t static, and not all polling locations will require the same amount of resources year over year. It is good for everyone that polling locations are appropriately staffed and equipped with enough ballots and machines to get the job done.

For all of these reasons, federal law requires that every state do list maintenance, and also requires that they do so in a “uniform and non-discriminatory” way. So if you are going to follow the law without removing people unnecessarily, ERIC is your best option. “States and counties are required to remove ineligible voters, but that’s good for the accuracy of the election and it’s good for voters,” said Shane Hamlin, ERIC’s executive director.

As we discussed last week, ERIC’s most commonly reported data point is folks who have moved and who have not updated the elections office with their new address. And who does that? I barely even do that. It’s not your first priority when you move. When I finally did send a letter to the New York City Board of Elections in 2019 to have my name removed, they apparently ignored it, because I get phone calls meant for registered New York voters three years later. No surprise: New York isn’t a member of ERIC.

Becker says that states without ERIC “put all of the burden on the voter to keep a state’s records up to date, and voters don’t do this because they don’t think about voting between elections.” But voters almost certainly will update their drivers license when they move, and ERIC has that data, allowing states to send mail to the new address reminding the voter to update their registration. This ability to proactively serve voters ensures that individuals don’t show up at the wrong polling location or have to resort to casting a provisional ballot — something all activists (and really everyone) should support.

Our four newsletters devoted to ERIC may seem like a lot for a single issue in election administration. But as I said when we started this journey, debates like this rely on a common understanding of the truth. And the truth, folks, is that ERIC is among the most significant advancements in fair, nondiscriminatory election administration in this country. We shouldn’t allow the debate to be swayed by bad-faith arguments made by conspiracy theorists and grifters.

Back Then

In 1879 Republicans in San Francisco designed and passed the “Act to regulate the registration of voters, and to secure the purity of elections in the city and county of San Francisco.” That language sounds surprisingly familiar, doesn’t it? It was primarily aimed at undercutting the up and coming Workingmen’s Party, and removed elections from the purview of the elected board of supervisors and instead assigned them to a board of commissioners made up of the city’s mayor and four county officials who were appointed. It also created a registrar of voters who was to be appointed by the governor, and had the ability to remove voters from the roll if they were suspected of fraudulent registration. It also required that voters register in their individual precinct by ending citywide and countywide registration. No precinct could include more than 300 voters. Anyone who moved out of their immediate neighborhood was required to re-register.

In Other Voting News

- A stunning analysis of the Texas primary by the Associated Press shows that nearly 23,000 ballots were rejected across the state during the recent primary, largely as a result of the new ID requirements passed by the legislature last summer. This amounts to roughly 13 percent of all mailed ballots cast.

- The U.S. House Oversight Committee has announced an investigation into a partisan review of the 2020 election in New Mexico. The Republican-led probe in Otero County called for canvassers to go door-to-door to check voter registrations, which the committee has said may amount to voter intimidation.

- Kansas lawmakers are considering felony-level penalties for election workers who mishandle ballots, based almost entirely on one Republican’s concern that ballots went missing in a single county in Kansas back in 2010. Democrats say the move is unnecessary and that Kansas’s elections are secure.

- Michigan lawmakers are also considering a slew of restrictive bills, but these are likely to be vetoed by the state’s governor.

- Washington Secretary of State Steve Hobbs has requested an increase in funding in this year’s budget to accommodate updating election infrastructure and shoring up cybersecurity standards across the state.

- Fox News has countersued Smartmatic, alleging that the voting machine company inflated its estimate of $2.7 billion in losses resulting from Fox News’s consistent misinformation campaign. Fox’s key evidence is a report by a University of Chicago business professor who indicates Smartmatic’s losses are merely in the millions, not billions.

Infographic of the Week

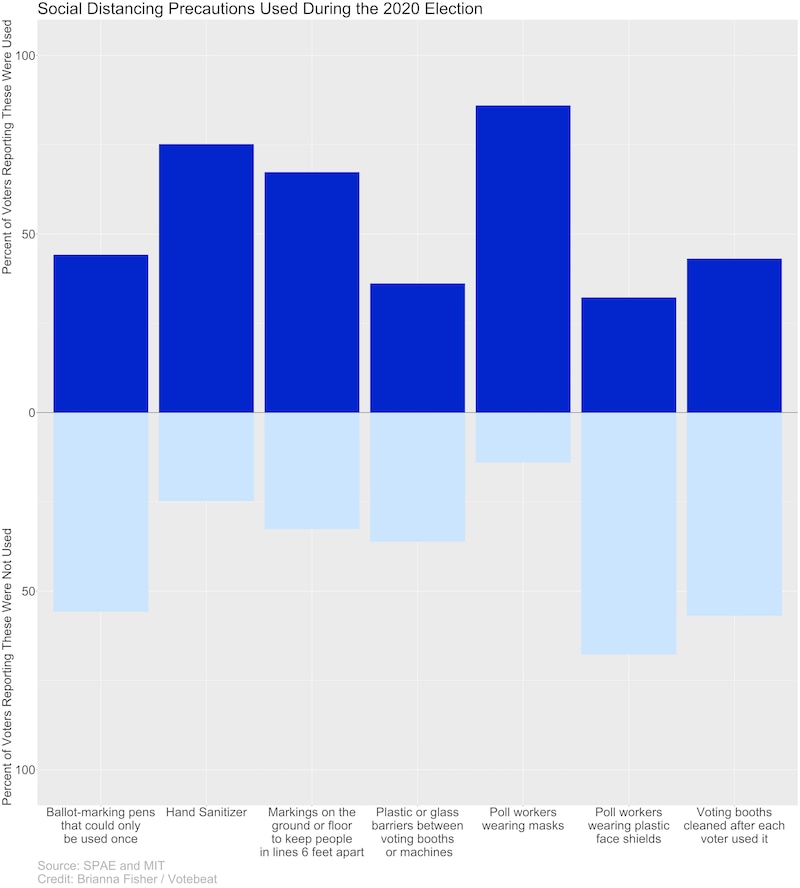

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

This week I’ve taken a look at the precautions polling locations chose to use during the 2020 election to accommodate voters during the pandemic, compiled in MIT’s Survey of the Performance of American Elections. While poll workers in most places used masks, hand sanitizer, and markings on the floor to space out voters, only a minority of voters saw polling locations using, for example, barriers between voters.