A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

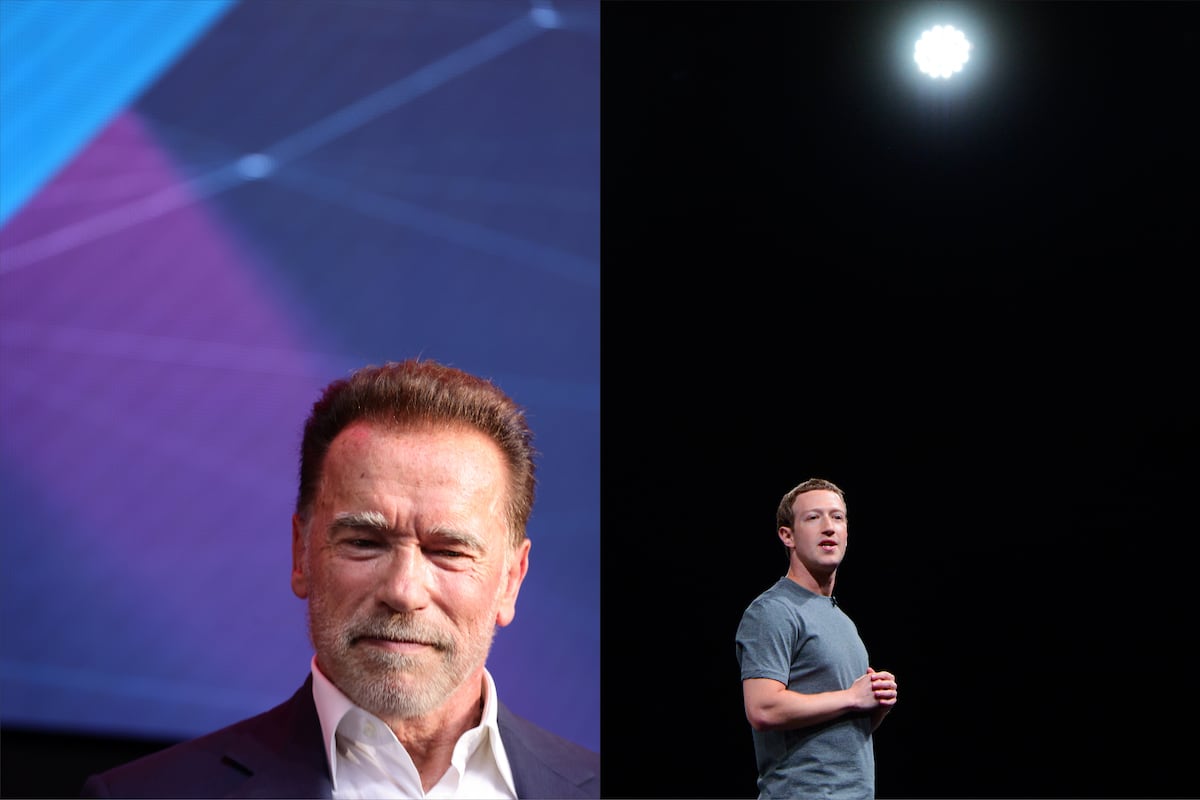

In our last newsletter, we discussed the fervor around banning private grants to election administrators — all centered around grants primarily administered by the Center for Tech and Civic Life and funded by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, in 2020. Today, let’s discuss how one-sided, unfounded, and myopic the conspiracy truly is.

As we already explained, there is a reasonable argument to be made in favor of banning these types of donations. It would be less than ideal if rich people were able to use their money to dictate how elections are administered. Even the organizations that dispersed Zuckerberg’s money have repeatedly said that, really, they’d prefer a predictable federal funding stream. In fact, Zuckerberg’s already said the grants were a one-time donation meant to address crisis needs during the pandemic and he won’t be continuing them.

None of that seems to matter. Trump and his allies have begun to cite these grants to explain his loss, and these grants have thus become a target in a way that isn’t borne out by the facts.

Let’s take, for example, the new movie from the nonprofit Citizens United, which is headed by Trump ally David Bossie. It’s called “Rigged: The Zuckerberg Funded Plot to Defeat Donald Trump.” It centers on the claim that Zuckerberg’s 2020 election spending was meant to boost Democrats’ prospects. The movie says Zuckerberg spent nearly $400 million on “voter operation efforts, particularly in the battleground states of Wisconsin, Arizona, and Georgia.”

But as has repeatedly been reported, the amounts that went to each county were essentially determined by the counties themselves. Every county that applied got funding, and they got the full amounts they asked for. The effort was not targeted at any state, nor was it tailored for any particular voting strategy. Zuckerberg, via a spokesman, has previously said the couple did not participate in determining which jurisdictions should get the grants. It was an infusion of funds, spent at the discretion of the local election officials.

But there was, in fact, a funding campaign that was targeted and did ask counties to spend it in a specific way. The donor: movie star and former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican and very-popular-man-of-the-internet. Unlike Zuckerberg’s $400 million, Schwarzenegger’s money — which came in at just under $2.5 million — was doled out in response to years of progressive advocacy around polling closures affecting communities of color. He distributed the money only in states that, because of a history of racial discrimination in voting, were formerly required under the Voting Rights Act to seek permission from the Department of Justice for polling place reductions and voting changes. The Supreme Court struck down that requirement in a 2013 decision, Shelby County v. Holder, prompting an outcry. Schwarzenegger said he was spurred by reports of poll closures, and his grants were explicitly earmarked for costs related to in-person polling locations.

“Most people call closing polls voter suppression. Some say it is ‘budgetary.’ What if I made it easy & solved the budgetary issue? How much would it cost to reopen polling places?” he tweeted in September 2020. Three days later, he announced he’d invited nearly 6,000 counties to apply for grants and promised responses “within a week” of applications being submitted. He made good on his pledge, distributing money to counties in Georgia, Texas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Arizona, Virginia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

So here’s a funding stream that does all of the things Republicans have decried: target specific states in an attempt to have elections administered in the way a rich person wants them to be. For Arnold, that meant paying to expand in-person voting in the middle of a pandemic. Cameron County, Texas, for example, got $250,000 to open two additional voting “supercenters.” They applied on a Friday, and received word they’d get the money the following Monday. The county also got money from CTCL, and the so-called “Zuck Bucks” were not nearly as specific. Those grants were used by counties around the country to shore up almost every aspect of voting, from poll worker pay to new scanners and tabulators. There were no limitations or restrictions.

Still, Zuckerberg’s grant program — not Schwarzenegger’s — led to multiple lawsuits, and is being cited by name as states ban private donations in the future. Surry County, North Carolina, was a rare exception. There, election administrators applied and were approved for more than $63,000 before county officials backtracked and refused to accept the Schwarzenegger funds. They also rejected a smaller grant that had been approved by CTCL. Let me know if there are others like this.

Christian Grose, a political science professor at the University of Southern California who leads the USC Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy, which administered the grants, said there are probably a lot of reasons that their grants did not attract the same level of ire. “Well, the ‘Schwarzenegger’ name is different from ‘Zuckerberg,’” he said. “I think that’s part of it.”

And unlike CTCL, the institute is associated with a university, which administered the grants.

“If they did start criticizing and pulling the layers back, what they’d find is students working and learning and election administrators speaking to classes,” he said.

But, of course, there are a few more things: Certainly, Schwarzenegger gave less money to fewer counties. He’s a Republican. Unlike Zuckerberg, he doesn’t run a social media network that conservatives have alleged for years is biased against them. He distributed money specifically for in-person voting, which has drawn less Republican criticism. And maybe, state lawmakers just don’t want to take on the Terminator. Pick your poison.

But really, Grose is just as puzzled about the aggressive stance against Zuck Bucks as anyone. “It’s not like the goals were different [than CTCL’s], but I do think his image and his name make it harder to attack the grants,” he said. “Gov. Schwarzenegger has established himself, in the last several years, as a post-partisan person that works with everyone.”

So, will he … be back?

Unclear. Grose said the institute plans to work with election officials to help them become better advocates for funding, but future grants haven’t yet been discussed.

If the efforts to shut down private funding were being made in good faith, Schwarzenegger should, minimally, be mentioned alongside Zuckerberg — but he hasn’t been. And here’s what that tells us: This is not a serious policy debate about the potential implications of election funding by the wealthy, even though it should be.

Election administrators: Talk to us about these grants. Did you use the 2020 private grant funds to buy equipment new state laws no longer allow you to use? Are new restrictions on private grants causing unanticipated problems or prompting new creative solutions? Please email us at tips@votebeat.org and tell us about it. Votebeat would love to hear from you.

Back Then

Throughout American history the power and privilege of the rich have been a central source of concern in elections. But most of the time, American politicians were worried that the rich might have less influence than they should — not the other way around. This was the justification for property and wealth requirements for the franchise. In New York state in 1821, James Kent — chancellor of New York, the head of the New York Court of Chancery, which was the highest court in the state until 1847 — argued that such requirements were necessary in order to protect “against the caprice of the motley assemblage of paupers, emigrants, journeymen manufacturers, and those undefinable classes of inhabitants which a state and city like ours is calculated to invite. This is not a fancied alarm. Universal suffrage jeopardizes property, and puts it into the power of the poor and the profligate to control the affluent.”

In Other Voting News

- Run for Something, a Democratic group, is beginning to recruit candidates to run for local election administration positions in 35 states. The program, which will run for three years, aims to train 5,000 people.

- The New York Times is out with a piece on the wedge Trump is driving in Michigan, between loyalists who continue to repeat his false claims about the 2020 elections and Republicans who “are eager to move on.”

- South Carolina offered what appeared to be a shining ray of bipartisan agreement when the state Senate unanimously approved early voting in the state. The state House had passed the measure earlier this year. But AP reports the House and governor are now accusing the Senate of a power grab for giving itself the power to confirm gubernatorial appointees to the state elections board, and the legislation may die as a result.

- Georgia Public Broadcasting’s Stephen Fowler has a new episode of his excellent podcast series “Battleground: Ballot Box.” This time: How election officials banded together to prevent even more election changes in Georgia from passing. It’s worth your time.

- Kim Crockett, a leading Republican candidate for secretary of state in Minnesota is fundraising off of her claims that “socialist” secretary of state candidates shouldn’t be elected because they will have the power to count votes. Except that — oops — the secretary of state is in charge of no such thing.

- Not all polling closures are bad! Exhibit A: Dallas County. The county will shut down around 40 lightly frequented polling places to solve staffing shortages and long lines at more heavily used polling locations. Dallas allows you to vote at any polling location in the county, meaning that staff and resources can be redistributed where they make the most sense.

- Republicans in the Louisiana House appear to be against even studying the possibility that disabled voters might need additional accommodations, like curbside voting. A bill that would have gathered a group of experts to study the issue faced heavy pushback this week, with Republicans advocating that disabled voters simply get help from non-disabled people instead of being provided accommodations.

- Controversial conservative activist Dr. Steven Hotze and co-defendant Mark Anthony Aguirre have been indicted in Houston for “unlawful restraint, a third-degree felony, and aggravated assault, a second-degree felony.” Hotze had hired Aguirre, a former police captain, to investigate ballot fraud. Mistakenly believing a repairman was carrying hundreds of fraudulent ballots in his truck in October 2020, Aguirre ran the man off the road and held him at gunpoint. There were no ballots in the truck, which contained only air conditioning parts and tools.

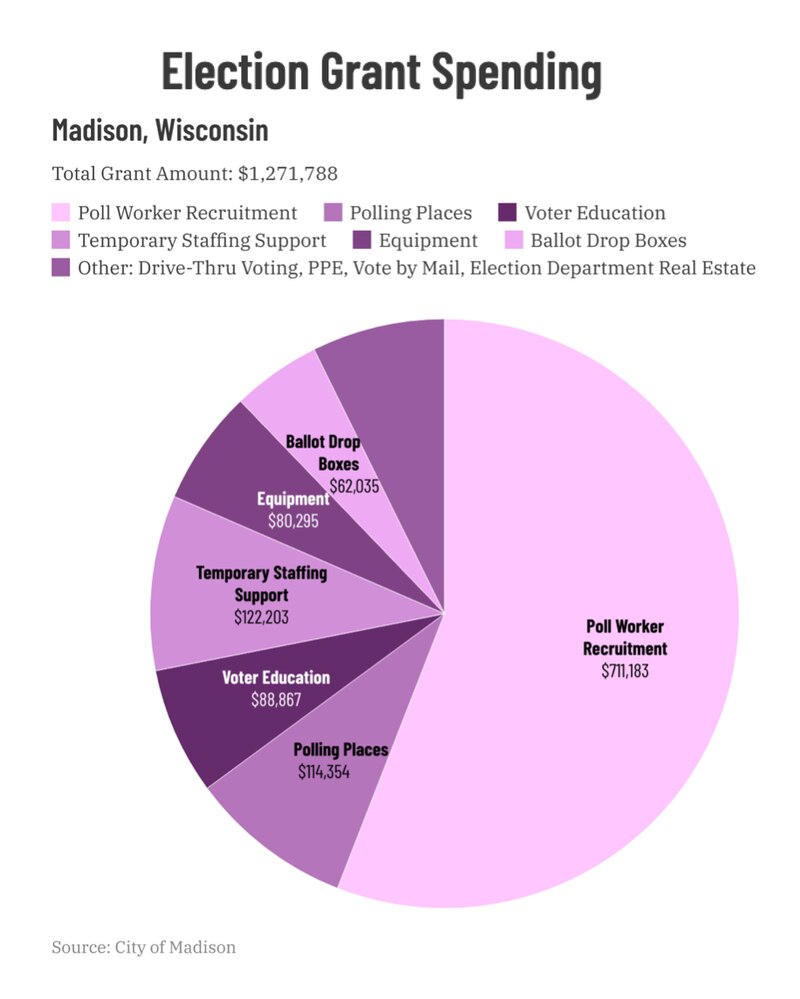

Infographic of the Week

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

As you read in this newsletter recently, Zuckerberg-grant-related conspiracies are gripping Wisconsin. So, this week I decided to illustrate how Madison, Wisconsin, used its grant money as one example.

Republicans in Wisconsin passed legislation to ban such grants, but Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, vetoed it. Where does that leave local election officials in Wisconsin? Celestine Jeffreys, the Green Bay, Wisconsin, city clerk, says that “presently, and in the future, we will fund elections with city-budgeted funds.” So far, Wisconsin lawmakers haven’t announced any plans to increase public funding to make up for those dollars.