A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

You’ve seen the news: House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy lied, and there’s audio proof. While he initially flatly denied that he told other Republicans he would encourage Trump to resign after Jan. 6 — describing reporting by the New York Times as “totally false and wrong” — audio released on MSNBC by the NYT reporters was pretty clear that’s exactly what he said. McCarthy nonetheless continued to lie late last week, even after the audio became public, telling supporters in California that he “never thought that [Trump] should resign.”

McCarthy is far from the first politician to lie to the public. It’s not always possible to immediately disprove such untruths. And if the truth comes out later, the damage often has already been done. As more texts have come out from the Jan. 6 Commission, there have been other nasty little examples.

Less than 25% of the American public said they trusted the government as of last year, and we haven’t eclipsed 30% since 2007. This is not fine. The lies — big and little — have reached a fever pitch, and the public sees it. A lot of the folks who read this newsletter are public officials, and I know only a small fraction of public officials participate in the kind of brazen dishonesty we are calling out here. But public sentiment on this creeps, and it has crept right on up to elections.

Still, there’s a lot we can do. Last week, I moderated a panel on state innovations in combating misinformation at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs, hosted by their Certificate in Election Administration program. One of our reporters, Jen Fifield, participated on a panel on the debacle in Maricopa County. The conference drove an important point home for me: Yes, reporters will hold you accountable when necessary. But we are also here to help you do a better job communicating truth to the public in an efficient, proactive, and nuanced way. Election officials can work with the media to get ahead of misinformation, and to make themselves a source the public trusts.

Here’s how you can help reporters help you further your education campaigns and ensure the maximum number of voters have the information they need to cast a ballot:

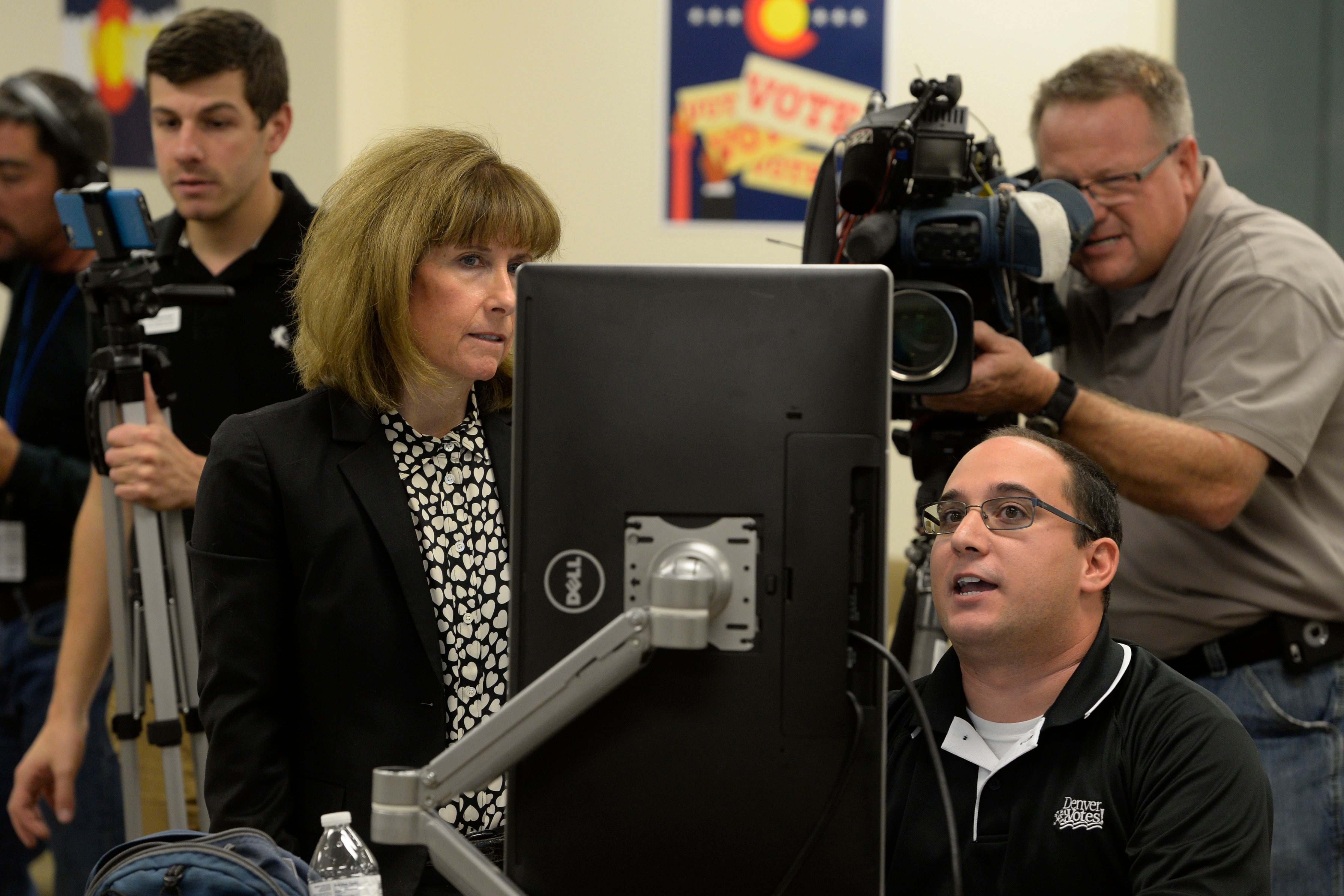

- Allow TV reporters into your facilities on a slow day — let them gather footage of the machines, how counting works, and the people doing the counting. This will pay dividends as Election Day nears.

- Open up logic and accuracy testing to the public, or let the media film it. Explain what you are doing during each step of the process.

- Be candid about the challenges you are facing (Funding? Staff shortages? Proposed laws that would make your job impossible to do?) when speaking with local reporters — often, media coverage leads to change.

- Help reporters file better records requests. Have they not requested quite the right thing? Is the way they requested the information incredibly burdensome for you? Tell them. Reporters are willing to refile in order to make your life easier (and theirs too!).

I want to highlight one terrific example of proactive engagement here, that I think is a model for other states: The North Carolina State Board of Elections. I mean, have you seen their website lately?

Folks, this place has everything. It’s got a breakdown of logic and accuracy testing and ballot proofing. It’s got a myth-busting archive that compiles their regular “Mythbuster Monday” posts, which proactively address misinformation before it takes hold. It has a list of what poll watchers are and are not allowed to do, available all the time and not just around elections. It tells voters how to access their own file, what’s in that file, and why. It is, and I mean this genuinely, one of the best, if not the best, state elections website in the country.

Now, you may be saying, “I have all of this information, but the media never asks me for it.”

I hate to tell you this, but the media often has no idea they should ask.

Prior to covering this full time, I don’t think I really even knew that states had secretaries, or that there were codes specifying the reasons ballots might be rejected. Like the public, many members of the media don’t know that logic and accuracy testing exists, and they have never had occasion to consult the state elections code. They also — like many of you — likely have an incredible number of responsibilities that make it impossible to engage as deeply as is likely necessary to understand these nuances. While you may once have had a county government reporter, that person probably also covers courts, education and the city council these days. Newsrooms, like counties, are strapped.

And similarly, most election officials are often their own public information officers. News reporters call expecting a comms person, and they get…you! Or someone exactly like you!

What helps you both: Offering proactive information that is easily accessible, easily understood and addresses misinformation before it starts. That’s what North Carolina has managed to do here.

States can help you get ahead of misinformation by hosting websites of this caliber. They allow counties to send this information out to local reporters proactively as soon as they hear of problems. Reporters, likewise, do not have to wait for you to explain which voting machines you have, because that information is just sitting there. They also don’t have to wait for you to explain to them why the latest piece of misinformation about mailed ballots is wrong, because the FAQs on your website do that for you.

Everyone loves to talk about “trusted sources,” but part of being one is being proactive and having the information easily available to the people whose job it is to magnify your message. You cannot be a trusted source of information if the only information you make available comes out on your Twitter account, which is only followed by 115 people who were already engaged enough to seek out their local elections office.

The public has been inundated with messages about the ineffectiveness of government, and repeatedly confronted with politicians who lie with impunity. It is no wonder that they have lost faith. Building it back won’t be easy. But it’s necessary.

How To Do This

This week there were, count them, two media reports in Washoe County, Nev. that resulted from the type of proactive media engagement I endorse above. First, the local NBC affiliate published a video, a diagram, and a detailed look at the steps the county takes to securely count ballots — after they were given a tour of the county registrar’s office. Second, Jaime Rodriguez, Washoe County government affairs manager, sat down for what looks like a pretty in-depth interview with the Reno Gazette Journal on the top three mistakes voters make when mailing in their ballots. The article contains useful, actionable advice that voters can use to avoid having their ballot rejected. The public needs more of this.

In Other Voting News

- In other Kevin McCarthy news, recordings released this week by the NYT also show that he feared several members of his party put “people in jeopardy” with their false claims about the election. “Mr. McCarthy referred chiefly to two representatives, Matt Gaetz of Florida and Mo Brooks of Alabama, as endangering the security of other lawmakers and the Capitol complex,” reported the NYT. “But he and his allies discussed several other representatives who made comments they saw as offensive or dangerous, including Lauren Boebert of Colorado and Barry Moore of Alabama.”

- Reuters reported this week that the local Republican Party leader in Surry County, North Carolina ,threatened to have the local elections administrator there “fired or have her pay cut unless she helped him gain illegal access to voting equipment.” Trump won the county by more than 75%. This is the latest in a series of incidents involving Trump loyalists attempting to gain unauthorized access to voting systems across the country.

- New Mexico is taking a tiny step toward open primaries in the form of a quick process to change your voter registration at your polling location. It’s an option now open to those unaffiliated with a party or affiliated with a minor party, and reversible.

- Election administrators are getting nervous about the dates of upcoming elections in New York as legal challenges to the maps passed by the state’s Democratic majority are considered in court. If the legal challenge continues or the maps are thrown out, Gov. Kathy Hochul says the state will consider moving the June 28 primary.

- Voting rights groups filed lawsuit in a Leon County, Florida, circuit court, seeking a temporary injunction to block the congressional maps passed by the Republican Legislature earlier this year. The suit claims the maps violate 2005’s “Fair Districts amendment,” which sets redistricting standards for the state.

- New Hampshire Secretary of State David Scanlan has created a commission that aims to restore voter integrity in the state after 2020 brought swirling misinformation and trumped-up claims of voter fraud.* They might want to start with Ken Eyring, one of the commission’s appointed members, who wrote all of these things.

- Texas Public Radio reports that the upcoming May elections will be the most expensive in Bexar County history. The county, home of San Antonio, has been forced to have three separate elections at the same time and also must adjust to new state laws that require the purchase of new materials.

- The Kansas Legislature has passed an unfunded bill that will require counties to use watermarked ballots, to make sure — as the author of the bill says — they are “verifying things to the max.” The author did not know how much the change would cost, but it’s probably around $1 million.

- Even as every Republican running to replace Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill has declared election integrity to be among their gravest concerns, Merrill is assuring voters that the upcoming election will be secure.

Correction, May 2, 2022: This post originally misidentified New Hampshire Secretary of State David Scanlon as Dan Scanlon.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.