Sept. 15 is Democracy Day. This is an international day designated to promote and uphold the principles of democracy.

Votebeat has contributed reporting to the Democracy Day journalism collaborative, a nationwide effort to shine a light on the threats and opportunities facing American democracy. Our contribution covers a new lawsuit in Texas that alleges that True the Vote targeted a small election vendor with a racist and defamatory campaign and cites the group’s own public claim that it hacked the company’s servers.

But at Votebeat, Democracy Day is every day. We are always working to strengthen and protect American democracy with our reporting on elections and voter access.

With that in mind, here are a few stories we’ve written lately that debunk misinformation and reveal new information about the forces seeking to undermine elections.

The truth about ERIC and voter roll maintenance

A common refrain you may have heard from right-wing politicians and activists is that people can be registered to vote in different states at the same time. With this often comes a call to clean the voter rolls.

The good news is there’s already an entire system that helps remove duplicate voter registrations across state lines. It’s called The Electronic Registration Information Center, or ERIC. This program is trusted by most states as the most effective way to perform cross-state voter registration checks.

For example, if it weren’t for a report Arizona officials received for the first time in December, election officials might not have realized that around 200,000 voters had potentially moved to another state. This report came from ERIC and allows officials to maintain accurate voter rolls nationwide.

What a “cast vote record” is and why right-wing activists want it

Elections departments across the country are getting tons of near-identical public records requests for an obscure document generated by ballot-counting machines. This has been spurred by people who insist this record could help detect fraudulent voting patterns that show former President Donald Trump actually won the 2020 presidential election.

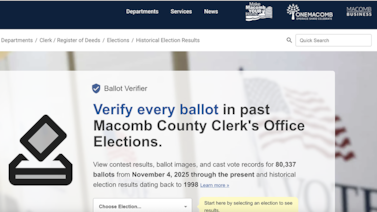

This document is called a “cast vote record” and it won’t prove the fraud they’re looking for. This technical record is really only particularly useful for researchers or auditors, experts say. Put simply, it’s an electronic spreadsheet documenting the order in which ballots were scanned by the tabulator.

These requests are the latest example of the endless, fruitless quest for a smoking gun that has so far yielded no proof of wrongdoing affecting the election results. But the sheer number of requests is overwhelming election offices as they prepare for this year’s general election.

Why unrestricted ballot access means less secure elections

In August, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton released a legal opinion that argued in favor of letting anyone examine ballots as soon as right after Election Day. (This opinion contradicts advice issued by his office just five days earlier.)

The opinion invites lawsuits over long-established ballot security and subjects election officials to possible criminal charges. Federal and state law both require that ballots be kept secure for 22 months after an election to allow for recounts and challenges — a timeframe Texas counties have had set in place for decades.

Paxton’s opinion theoretically permits anyone — an aggrieved voter, activist, or out-of-state entity — to request access to ballots as soon as the day after they are counted. Such requests have been used by activists all over the country as a way to “audit” election results. Allowing immediate public access to the ballots prevents a serious security risk to the election, experts say.