Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

Redistricting is supposed to be a way to ensure equitable representation. Americans adjust political boundaries at all levels to make sure districts are equal, population growth is accounted for, and everyone’s vote is meaningful. But in practice the process is a bare-knuckled no-holds-barred political mishegoss that would shatter anyone’s ideals.

This week’s federal court ruling in Alabama, after nearly three years of rancor, puts this in sharp relief.

In 2021, Black registered voters from Alabama sued the state over its political maps, alleging intentional discrimination and racial gerrymandering. Alabama lost the case. Federal judges ordered the state to create a second congressional district in which Black voters comprised a majority, or nearly so.

Alabama appealed and the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The state lost there, too — resoundingly.

The case then went back to the lower court, which gave state lawmakers time to call a special session and take another crack at drawing political maps complying with the court’s orders.

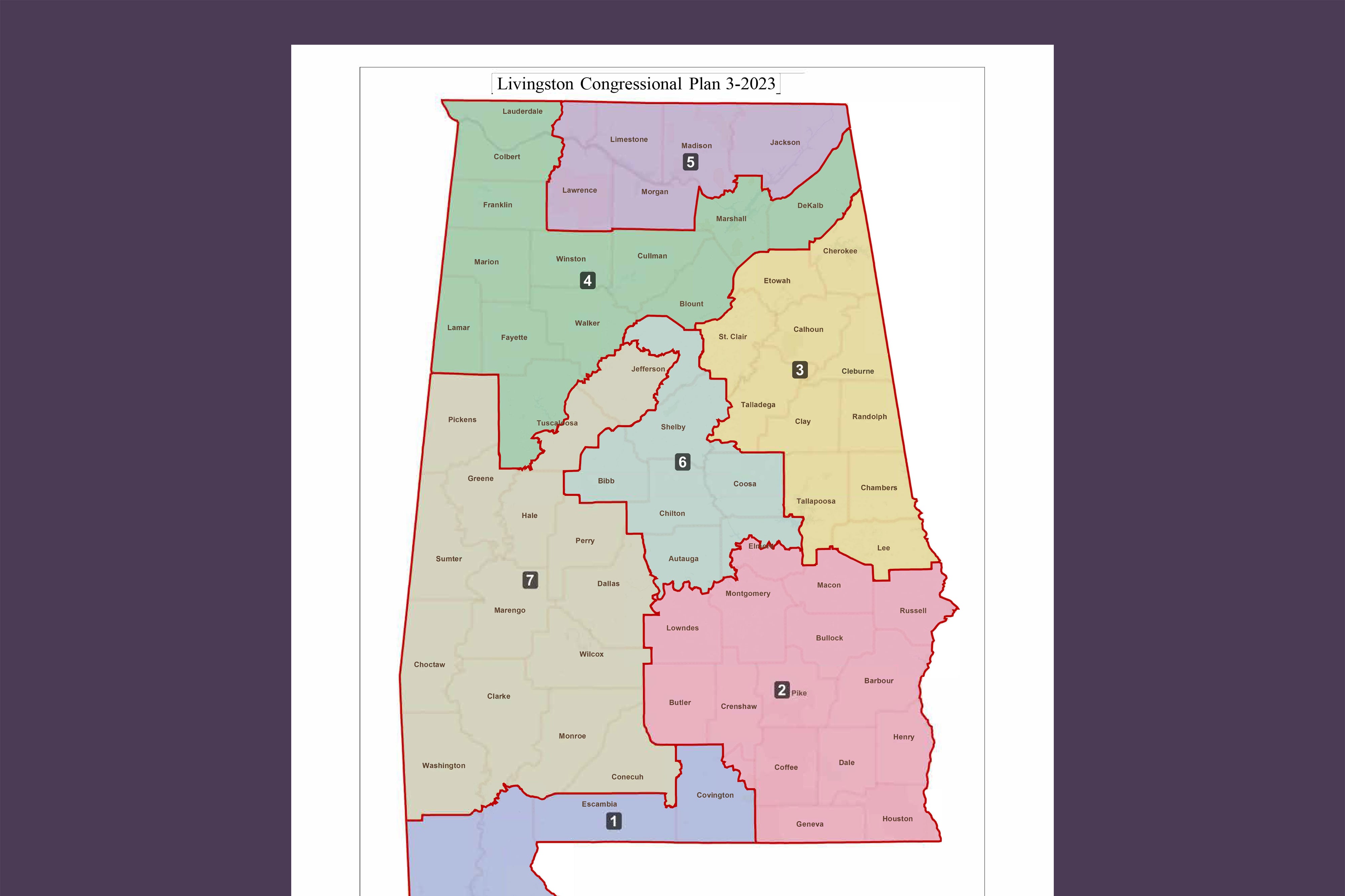

But the Alabama Legislature, once again, produced a map that didn’t create that second majority-Black district.

So here we are, more than three-and-a-half years into the 2020 redistricting cycle, and these voters, who already decisively won their case in the U.S. Supreme Court, are back in federal court, still trying to get a fair map in place before the 2024 election.

Alabama — like so many other states before it — is running out the clock.

After all, the 2022 election was conducted based on an illegal map in Alabama, one that denied Black voters the representation they were entitled to under the law. Similarly, Ohio used a map the state Supreme Court had declared illegal after a federal court decided the state was out of time to put a fair one in place. The wrangling has gone on so long there, advocates who brought the lawsuit this week moved to drop the litigation and leave the current map in place because of “the continued turmoil brought about by cycles of redrawn maps and ensuing litigation.”

There’s a redistricting trial underway over Georgia’s map and a challenge pending over Louisiana’s. A state judge just decided Florida’s map doesn’t comply with the state constitution. In Wisconsin, a shift in the makeup of the state Supreme Court has Republicans threatening to impeach a newly elected justice who has yet to hear a single case, in hopes of preserving Republican-drawn state legislative maps. And that’s just a partial list.

This isn’t the first time, certainly, that a redistricting cycle has gone into what Michael Li, senior counsel to the democracy program at the nonprofit Brennan Center for Justice, describes as “extra innings.” But there are a lot of states still in flux, even if Alabama appears to stand out for sheer nerve.

And it matters.

Republicans narrowly won control of the U.S. House of Representatives in 2022, and small shifts — such as a second majority-Black congressional district in Alabama that’s likely to add a second Democrat to the state’s congressional delegation — could tip the balance next year.

It’s cynical, but it’s easy to see how that gives politicians a reason to drag out legal proceedings for as long as possible — and maybe keep a map in use for another election cycle, even if it’s eventually going to get thrown out.

“I think it can be disillusioning,” Li said. “People who are affected win things and then they don’t get them. It seems like it’s forever stalled in an appeal.”

The three-judge panel dealing with the Alabama case, all of whom were nominated by Republican presidents, including two by former President Donald Trump, clearly took note of the state’s intransigence in a 217-page order issued Tuesday.

“The State has explained that its position is that notwithstanding our order and the Supreme Court’s affirmance, the Legislature was not required to include an additional opportunity district in the 2023 Plan,” the judges wrote, sounding baffled at how, exactly, the state might have arrived at that particular conclusion.

“We discern no basis in federal law to accept a map the State admits falls short of this required remedy.”

The judges’ order, dotted with phrases such as “as we already said,” did not sound pleased. Far from it.

It’s clear Alabama’s legal strategy here isn’t landing, though the accompanying political strategy may be easier to understand. One state representative told the court that during the special session held earlier this year to draw a new map, he spoke with U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, a California Republican. McCarthy, he told the court, “was not asking us to do anything other than just keep in mind that he has a very tight majority.” State lawmakers may have, indeed, kept that in mind.

The judges wrote that they are “deeply troubled” by the state’s actions and “disturbed by the evidence” that even though “we have now said twice that this Voting Rights Act case is not close,” the state simply is not going to do what it’s been ordered to do.

“We are not aware of any other case in which a state legislature — faced with a federal court order declaring that its electoral plan unlawfully dilutes minority votes and requiring a plan that provides an additional opportunity district — responded with a plan that the state concedes does not provide that district,” the judges wrote.

Of course, as Li points out, evoking George Wallace and the South’s response to court orders to desegregate schools, there’s a long history of such recalcitrance (something also not lost on opinion columnists) and resisting orders from the federal government may be a sounder political strategy than a legal one.

The court is now appointing a special master and cartographer to draw a new map, since, as the judges note, election officials need one no later than early October.

For its part, Alabama has already appealed the order. The state attorney general issued a statement saying, against all available evidence, that “we strongly believe that the Legislature’s map complies with the Voting Rights Act.”

Alabama is also likely to appeal whatever map the court puts in place. Most experts expect the state to lose.

But the clock is ticking. And the Black voters who won in court have yet to win the representation federal courts found they’re entitled to have. So even though federal judges have made their position crystal clear, it’s hard to tell whether anyone is really winning here.

Back Then

Alabama has a long history — as many states do — of discriminating against Black voters. In its Sunday edition on Aug. 24, 1902 — one year after the state adopted its new Jim Crow constitution — The Montgomery Advertiser published the following: “One of the great desires of the patriotic Alabamian is absolutely fair elections, primary and general. Under the new Constitution and the elimination of the negro this result is of easy accomplishment. The things that were done in the past which the necessities of the case may have pardoned is generally admitted, but now, with practically white suffrage only, there can be no excuse of cheating at the polls or manipulation after they close.”

New From Votebeat

From Votebeat Arizona: “I just hope it ends”: Maricopa election official shares emotional story as harasser sentenced to prison

From Votebeat Pennsylvania: Bill to move Pa.’s spring primary earlier would put time crunch on election officials

From Votebeat Texas: New law requires many Texas counties to add more polling places. In areas with few buildings and workers, that’s going to be hard.

In Other Voting News

- Amid protests, North Carolina lawmakers delayed a vote on controversial legislation that would realign the composition of state and local election boards, evenly splitting members between political parties and giving state legislators the power to break deadlocks, WRAL reported. Republicans have unsuccessfully pushed similar changes in the past, but voters rejected a constitution amendment in 2018, and the state Supreme Court twice rejected them as unconstitutional.

- Texas’ most populous county dismantled its election administrators office on Sept. 1 after a new law forced Harris County to transfer responsibility for elections to the county clerk and tax assessor-collector, the Houston Chronicle reported. The county sued the state to block it, but the state Supreme Court allowed the law to go into effect, even amid preparations for this November’s elections.

- Arizona Republicans rejected a plan to hold a presidential primary restricted to in-person voting on a single day with hand-counted ballots in favor of participating in the typical state-run primary, citing concerns about the money and manpower it would need but risking a potential backlash among a segment of the party who have pushed for such voting procedures, the Washington Post reported.

- Voters seeking to disqualify former President Donald Trump from running for office under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which says anyone who “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” after taking the oath of office is no longer eligible to hold office, sued in Colorado last week and also are seeking to keep him off the ballot in other states, the New York Times reported.

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s story editor and is based in Washington, D.C. She edits and frequently writes Votebeat’s national newsletter.Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org.