This article was co-published in partnership with The Guardian.

Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

In North Carolina, Local Labs wanted obscure voter records that would take weeks, or even months, to prepare. In Georgia, the company requested a copy of every envelope voters used to mail in their ballots. And in dozens of counties across the U.S., Local Labs asked for the address of every midterm voter.

Local election offices across the country are struggling to manage a sharp rise in the number of public records requests, and extensive requests coming from Local Labs in at least five states have stymied election officials, according to a Votebeat review of hundreds of records requests, as well as interviews. The requests are broad and unclear, and the purpose for obtaining the records is often not fully explained, leaving officials wondering in some cases whether they can legally release the records.

Local Labs is known for a massive network of websites that rely mainly on aggregation and automation, blasting out conservative-leaning hyper-local news under names such as the Old North News, in North Carolina, and Peach Tree Times, in Georgia.

Local Labs CEO Brian Timpone told Votebeat the company is using records requests in an attempt to expose election fraud that he is sure exists. The company is sometimes getting paid by GOP-backed clients to do so, Timpone acknowledged, characterizing the work simultaneously as both political research and journalism.

“We’re just trying to push for more free speech and more transparency,” Timpone said. “And no one else is doing it.”

Veteran journalists and those who study journalism ethics say he’s wrong. Arizona State University journalism professor Julia Wallace — previously the editor of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution — said doing reporting and paid-for work at the same time is not ethical. “That’s not independent, so that’s not journalism,” she said.

Timpone is no stranger to journalism controversies: Among his previous companies was one that sold cheap content to local news organizations and was ultimately closed after a series of ethics scandals, including plagiarism.

To be sure, public records laws exist because the public has the right to know what the government is doing, and ensuring access to records is a critical window into that. Election offices, open records advocates say, should consider proactively and publicly sharing more election records so there’s no request needed.

But election officials have questions.

It’s unclear from the requests when the company is doing the work for a third party or for their news websites, or both, and if the election offices can legally provide the records.

One recent Local Labs project offers a clue of what might be to come.

After the midterm election, Local Labs was paid by America First Policy Institute (AFPI), a national think tank that pushes former President Donald Trump’s agenda, to send public records requests to 100 counties in the U.S. asking for a record of each voter who voted, along with their address and other information. AFPI published the first results of that work in June, in a misleading report that insinuated that thousands of fraudulent ballots were cast in Arizona’s midterm election.

“Voter Discrepancies Found in the Arizona 2022 General Election,” the AFPI headline read. But most, perhaps all, of the more than 8,000 discrepancies found were because Local Labs had compared two sets of voter lists from different time periods and including different voters.

Yavapai County officials, for example, showed Votebeat emails in which an elections official tried to convince Local Labs not to publish the broad findings because they were misleading, taking time over days to explain the source of the discrepancies. The warnings went ignored.

“They just put the information out, and we are left defending ourselves,” Yavapai County Recorder Michelle Burchill said. “Then we are being harassed,” she said, because people believe it.

Journalism, political research, or both?

Local Labs is a piece of a network, owned in part by Timpone, that has a dubious history.

Timpone’s prior company, Journatic, imploded amid accusations of plagiarism. Multiple media companies canceled their contracts following a This American Life episode in 2012 that showed the company was using low-cost labor out of the Philippines to produce local news under fake bylines. That led the company’s editorial director to resign over ethical disputes.

Ahead of the 2022 election, nonprofits and political action committees paid Metric Media, another company within the network, more than $1 million, according to Columbia Journalism Review, and ProPublica found that special interest groups gave another company in the network, Pipeline Media, nearly $1 million. The local news websites associated with the network then published stories promoting the agendas of the groups that wrote the checks.

Local Labs advertises its public records request service to outside clients on its website, which says those clients include news publishers and media companies. Timpone confirmed that his network has received payment from and partners with GOP-leaning special interest groups, and that the network has not received payment from groups affiliated with the Democratic Party.

Because some election officials know Local Labs sells its records requests services, they have been unsure whether they can legally release some records, so they’ve reached out to clarify the purpose of the requests. Some voter and election information can only legally be released for non-commercial purposes. Local Labs employees, meanwhile, sometimes ask for fee waivers meant for members of the media, according to records obtained by Votebeat.

In Local Labs’ recent requests in North Carolina, for example, a person giving their name as “Vince Espi” writes that he is a news reporter for Old North News, “a media organization committed to providing comprehensive and accurate news coverage on local governmental affairs.” In Georgia, Espi says he is a reporter for the Peach Tree Times. When requesting voter data from Johnson County, Iowa in December, another employee, Josiah Chatterton, wrote the intended use was “primarily for the benefit of the general public.” When asked to clarify, because voter lists can only be legally released for certain purposes in Iowa, he said it was for “political research,” a legally permissible purpose in that state.

Asked why the requests should be considered non-commercial requests in the instances in which Local Labs is selling the records, Timpone said he considers their service to be “project management,” or gathering and organizing records, rather than selling them. Counties have occasionally disagreed.

In at least one previous instance, regarding an education-related request in 2021, a school district in Illinois told Local Labs that it will be treated as a commercial requester, though it had requested the information as “news media” and asked for a fee waiver.

“Local Labs does not obtain records for its own publication,” the district’s public records officer wrote. “Your organization provides public records for sale.”

Classifying Local Labs as a commercial requester is one potential option for local governments in some states that could allow them to recoup more of the cost of processing the requests, since some state laws allow higher charges for commercial requests.

Local Labs’ intentions were also an issue in a recent federal court case involving the Voter Reference Foundation, which has links to Trump allies and prominent conservatives. The New Mexico Secretary of State’s Office wrote in a court filing that Local Labs should have disclosed upfront that it was selling the voter data it collected to the foundation, a transaction the office said wouldn’t have been allowed under state law. But the Albuquerque-based federal judge ultimately decided the use of the data was legal after considering Voter References’ final use of the data rather than Local Labs’ sale of the records.

Timpone emphasized that Local Labs is filing the requests as journalists, while also sometimes assisting think tanks like AFPI “do thoughtful research where it hasn’t been done.”

But ASU’s Wallace said one of the fundamental principles in journalism, included in the Society of Professional Journalists ethics code, is to act independently.

“You are there to serve the public, you aren’t there to serve private interests,” she said.

Local Labs runs afoul of another core principle of journalism, being accountable and transparent: Vince Espi isn’t giving his full name.

Timpone confirmed the employee’s name is Vince Espinoza, and said he didn’t know why Espinoza had chosen to use a partial name when submitting requests.

Wallace from ASU said that part of being transparent as a journalist is being clear about who you are and who you work for.

“The first part of transparency is giving your real name,” she said.

Local Labs slams county offices with requests

North Carolina and Georgia election officials say they are frustrated by Local Labs’ broad requests because the company often fails to answer any questions that would make them easier to understand.

“I am reaching out for the third time to clarify your records requests to our county boards of elections,” Pat Gannon, spokesperson of the North Carolina State Board of Elections, wrote to Espinoza on August 17, asking him to call him.

“Obviously we will respond to all public records requests as required by law, but this is immensely frustrating to busy elections officials trying to ensure that all eligible individuals can vote and have their vote counted,” Gannon said.

Records provided by Gannon show numerous Local Labs requests across the state in recent months, for broad information that would take weeks to gather such as all documents with information about election hardware and software, and all absentee ballot applications. These add to outstanding Local Labs requests, including for all absentee ballot envelopes cast in the midterm election, which would take weeks to scan and redact.

In Wake County, North Carolina, it took a team of election workers three or four months to respond to a similar request for the envelopes from a different requester — there were more than 40,000 absentee ballots cast in the midterm election there. Danner McCulloh, who processes records requests for Wake County, said each envelope had to be scanned and redacted individually, and then reviewed by a legal team. The result was just envelopes with the voter’s name and address, since state law required the redaction of signatures and other identifying marks.

Local Labs asked for the envelopes along with any absentee ballot application from a voter — which would also have taken weeks to scan. When Stacy Beard, the county’s communications director, reached out to ask for clarification on what the company wanted, she said she never heard back. The county decided to pour its time into the request and send the applications anyway — but not the ballot envelopes, because it wasn’t clear what exactly Local Labs wanted.

“That kind of request,” Olivia McCall, the county’s elections director, said, “shuts an office down.”

Bartow County, Georgia, has received numerous extensive Local Labs requests, according to records provided by the county. Elections Director Joseph Kirk says he also hasn’t heard back when he tries to clarify exactly what the company is requesting, which makes him think it’s more of a fishing expedition than a true interest in the data.

“When you ask for any, and all, and everything for a four-year period, that really does put a hurting on offices, especially smaller offices,” Kirk said. “It’s not just something we can click a button and send out.”

In response to a request for all absentee ballot envelopes, similar to the one received by Wake County, Kirk told Local Labs that it would take one person working 163 days straight to provide the estimated 104,572 responsive records, and it would cost Local Labs about $23,000.

“We can try to get it done before then, but I hope you understand that registering voters and conducting elections must be our priority,” he wrote. He didn’t hear back.

Timpone said he’s trying to show the public that “these bureaucrats have been hiding the truth from them,” he said, adding that he believes “they are hiding the records from them, and deleting the records and covering their own asses and trying to blame, you know, Trump or some other politician for it.”

Timpone did not offer any definitive evidence that counties were illegally withholding election records. Asked why Local Labs sometimes didn’t respond when asked for clarification, such as to Gannon, he said he wasn’t aware that was the case. The same week Timpone spoke with Votebeat, Espinoza responded to Gannon.

Misleading findings in latest report

With regards to the America First report, Timpone said that Local Labs was trying to expose what he said is a problem — that counties don’t keep a fixed record of the voters who voted on Election Day and their voter status and address at that time.

In Yavapai County, Matt Webber, who manages voter records for the county, told Local Labs that, of the 139 “discrepancies” they found, 105 were secure voters — voters who are legally left off the list the county sent Local Labs because they are in a protected category, like law enforcement or a victim of domestic violence — and some addresses were not accurate because a small number of voters moved shortly before the election.

Still, the top-line finding from the America First report – that there was a “potential 8,241-vote discrepancy” across six Arizona counties — didn’t account for any secure voters, or the inter-county moves.

Webber and other Yavapai County officials said in an interview they were frustrated to see that. While the report broadly acknowledged that counties tried to tell them about such problems with their data analysis, the report authors still claimed it likely that “there are more votes than registered voters who voted.” This claim is false, Yavapai County officials said.

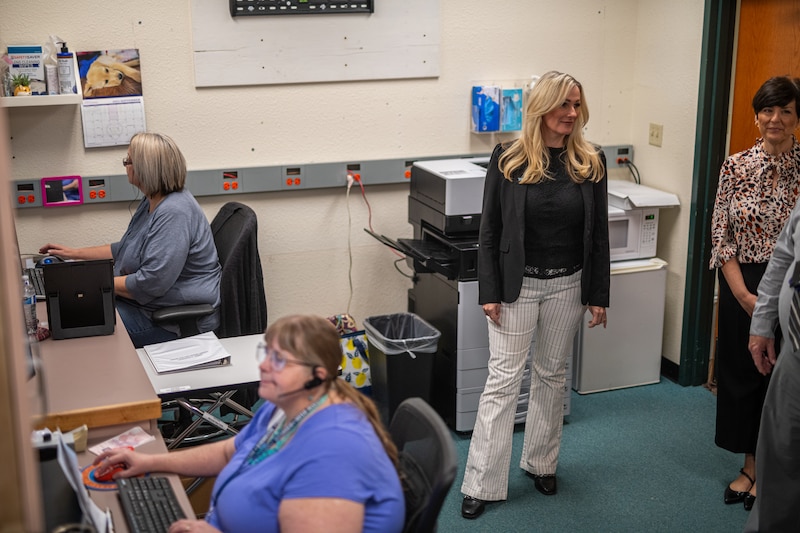

On June 29, Burchill — the Yavapai County recorder — released a public service announcement to combat the AFPI report. “There is no discrepancy [in] our numbers!” she wrote.

Burchill wants to remind voters that there are a lot of people online calling themselves election experts nowadays, but it’s best to just check with their county about specific claims.

“The only way we are going to win this is if voters come to us with questions.”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.

Freelance journalists Thy Vo, Matt Dempsey, and Hank Stephenson contributed research to this report.