Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

Recently the internet has been Freaking Out about artificial intelligence. I’m sure you’ve noticed.

The worries are not unfounded. Last month, what appears to be an AI-generated robocall in a voice made to sound like President Joe Biden went out to New Hampshire voters, telling Democrats not to vote in the upcoming presidential primary because it “only enables the Republicans in their quest to elect Donald Trump.” The caller ID made the call appear as if it had come from someone associated with the Biden campaign in the state. No one seems to know who is responsible.

That will not be the last time this happens. The horse, as they say, has left the barn.

So, I was excited to participate in a convening of scholars, election officials, and journalists in New York last week meant to at least begin to assess the potential impact of AI on the 2024 election. While I am well-acquainted with what one might describe as the beep-boop side of the journalism world, AI seemed overwhelming and scary to me prior to this. It’s still scary, but I’m — surprisingly — walking away less worried about it.

The program was the brainchild of Julia Angwin, an investigative journalist and author, and Alondra Nelson, a social scientist who served as acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy under Biden. It was the first program of their new initiative, AI Democracy Projects.

Participants were broken into groups and asked to test four AI language models, or chatbots, on a set of prompts about the election — how to register to vote by mail in a given county, where a voter could find the nearest polling location, etc. — and assess the quality and the differences of the responses. It’s certainly not a complete answer on the goodness or badness of any of the language models, but measuring the impact of new technology has to start somewhere.

Ultimately, what the day proved to me was that the problems AI may cause aren’t really that new, and that with appropriate collaboration between interested parties — in this case, election officials and AI leaders — the public can build up defenses appropriately, even if we might need to do so in a different way than we have before.

Quinn Raymond, who participated in the day, co-founded Voteshield, a program that monitors changes in voter registration databases to spot malicious activity, and analyze anomalies. He says he and his colleagues at Protect Democracy have been thinking about these problems a lot. “The consensus is that the threat of AI in elections is ultimately one of scale. Someone trying to disrupt an election is basically using the old same dirty tricks (imitation, intimidation, etc), but now the barrier to entry is a bit lower, and the verisimilitude higher,” he said in an email after the event. “So a comparatively small number of motivated individuals can do a lot of damage even if they start out with minimal knowledge and resources.”

The Brookings Institute has recently released a helpful explainer on AI’s possible impact on elections, with a realistic take on its potential for harm. It comes to a similar conclusion.

All of that sounds terrifying, I realize, but here’s why I’ve downgraded my own terror to “twingy discomfort.”

For much of the day, I was testing election prompts in a room with two local election officials from large counties, two academics, and a former federal official. I’d played with ChatGPT before, but certainly not in this way. And, honestly, it was surprising how dumb the responses were, sometimes flatly unhelpful to the point of uselessness. Language models are — at least for now — not quite there yet.

For example, when asked to locate the nearest polling location to a Koreatown zip code in Los Angeles, one language model popped out the address of a veterans center several miles away that is not a polling location. I realize that seems harmful: maybe a voter would rely on that information and show up. But ultimately, the answers make such little sense that it’s likely that person would ignore it or seek information elsewhere.

“For voters seeking information on how to vote, a basic Google search performs much better than asking any of the chatbots,” said David Becker, a participant in the conference and the executive director of the Center for Election Innovation & Research.

And, really, that makes sense given what AI is, says Raymond. “AI is fundamentally a technology about ‘guessing,’ and providing voters with accurate election information is fundamentally about ‘knowing,’” he said.

At least for now, it’s likely that a person sophisticated enough to seek out and use these language models for answers would pretty quickly realize they aren’t very good yet at election information and go elsewhere. Many of the public-facing models also explicitly label election information as potentially unreliable, referring users to local election offices or Vote.gov.

What was useful, though, was watching the election officials and the AI experts talk to each other. It’s a model for real collaboration in this area, and makes me optimistic about our ability to proactively address both the models’ shortcomings and the growing threat of disinformation as the technology becomes more sophisticated.

A robocall like the one in New Hampshire was inevitable. And this will keep happening. Like any evolving technology, experts and government officials need to rise to the occasion and update technology policies to address real-world conditions. For example, a handful of states are requiring images created using AI to be explicitly labeled. State-level attention to the issue has grown even since the start of the year, energized by the robocall.

This event was a great first step, and suggests that there really is common ground to be found on this important issue. Legislators working on bills should take note of the collaborative, interdisciplinary way Angwin and Nelson chose to approach possible solutions.

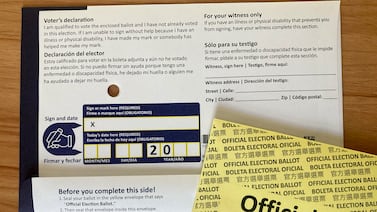

As I spoke to the election officials and journalists who’d attended the event, I realized that a common refrain was this: You just have to start playing with AI in order to understand it, and you shouldn’t be afraid to do it. Open ChatGPT and ask it questions. See what kind of images you can create with Microsoft’s Image Creator, and look closely for the tell-tale signs such generated images carry, such as not showing faces or distorting text. Try and clone your voice, and see what it sounds like.

Given how inaccessible the whole premise of AI seems, there is a real impulse to avoid engaging with it — as if it might shock us through our keyboards or take over our homes like that Disney movie from 1999. While an understandable response, it’s not a viable one if we — consumers of real information who attempt to assess that information in context — want to understand the pros and cons of this very real thing that is already having very real impacts.

If you want to dip your toe in gently, here are some good places to start (none of which require any previous knowledge to understand):

- AI Campus (an initiative funded by the education ministry in Germany) has a great video called “Artificial intelligence explained in 2 minutes: What exactly is AI?” AI Campus also contains free lessons on AI, all aimed at creating “an AI-competent society.” Cheers.

- “Artificial Intelligence, Explained” from Carnegie Mellon University is a great introduction to the various vocabulary words you might come across while exploring, and links out to helpful information on the history of AI’s development.

- Harvard University has an extensive site dedicated to AI. While it’s aimed at students, it’s open to all and contains really fascinating tools and suggestions for how to explore the seemingly endless options offered by language learning models. I specifically recommend their guides on text-based prompts and their comparison of currently available AI tools.

- We played a terrifying game in which a graduate student showed the room — full of experts! — a series of AI-generated images blended with actual photos and asked us to vote on which were real. There wasn’t consensus on a single image, and most people got most of them wrong. I certainly did. You can test your own skills in a similar quiz from the New York Times.

If you are an elections official who has concerns about this stuff, tell me what they are. I plan to remain engaged in this conversation, and Votebeat will certainly cover AI-related issues this year and beyond. Let us know what’s important to you.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.