Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

Good morning,

Wisconsin last month became the 28th state since the 2020 election to ban private funding for election administration, the latest in a remarkable wave of legislation.

The new laws all stem from a conservative backlash to millions of dollars in private grants awarded for the 2020 election that were primarily funded by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, but awarded by nonprofits. The wording of the bans varies from state to state, with some restricting the acceptance of private money and others also prohibiting the acceptance of free services and volunteer work.

That means election officials around the country, and organizations that work with them, have had to figure out what they are and aren’t allowed to accept or offer.

At an annual conference on Election Science, Reform, and Administration hosted by the University of Southern California in May, for example, organizers posted a sign on the lunch table reading, “Please Note: If you are a public official and do not have a speaking role at this event, the food and beverages are reportable gifts.”

An attendee said it had not appeared at past such conferences, though the language was approved by the legal affairs staff at the university and is used when public officials are in attendance at events, according to Christian Grose, the academic director of the USC Schwarzenegger Institute and one of the event hosts.

The ambiguity is contributing to a chilling effect among election officials, said Rachel Orey, the senior associate director of the elections project at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a nonpartisan think tank, as election officials under unprecedented scrutiny worry about making a misstep.

“The biggest challenge we’re witnessing is the uncertainty about what is covered,” Orey said.

The bans differ by state, and advice has been hard to come by. Organizations like the Bipartisan Policy Center that work with election officials across the country are worried about violating the laws themselves, as well as accidentally leading election officials to do so.

For example, Orey said, Ohio’s law banned officials from collaborating with nongovernmental entities, a restriction local election officials said would keep them from participating in the BPC’s advisory task force of election officials. But in 2022, the state attorney general issued an opinion saying the ban only applied to officials “acting in his or her official capacity,” leaving them to then wrestle with what that meant. Ohio election officials continue to serve on the task force, but the ambiguous wording wasn’t helpful.

A Tennessee law requires election officials to file a form with the secretary of state within 15 days of attending any out-of-state seminar, conference, or training program about elections, disclosing who paid for it, even if the official took no outside funding.

Others are also proceeding cautiously. The Elections Group, an elections consulting firm, typically provided many services to local officials pro bono, such as consulting on best practices for post-election audits or signature reconciliation. It has begun posting as much guidance on best practices as possible publicly on its website, said CEO Jennifer Morrell, such as guides to chain of custody or templates for posters that can be customized.

If officials in states with such bans want more consulting help or resources, she said, the Elections Group has to charge. Often, she said, election officials don’t have the budget to pay, “and we know that.” Because of that, she said, they’ve tried to post as many free resources and customizable templates online as they can.

Morrell, like Orey, said the laws have “a chilling effect on election officials who are reluctant to engage with outside groups for fear of accidentally violating the law,” stopping them from reaching out to outside agencies or organizations for help. “There’s probably a bigger effect than we realize,” she said.

In Florida, Mark Earley, the supervisor of elections in Leon County and a past head of the Florida Supervisors of Elections association, said he was initially concerned about whether the state’s law restricted election officials from participating in meetings run by outside groups, but has found that not to be so. Earley also said he is a member of the executive committee of the Elections Infrastructure and Information Sharing & Analysis Center, commonly referred to as EI-ISAC, run by the nonprofit Center for Information Security. He was worried he would have to absorb all the costs of his travel to EI-ISAC meetings, but is still allowed to let the group pay for that.

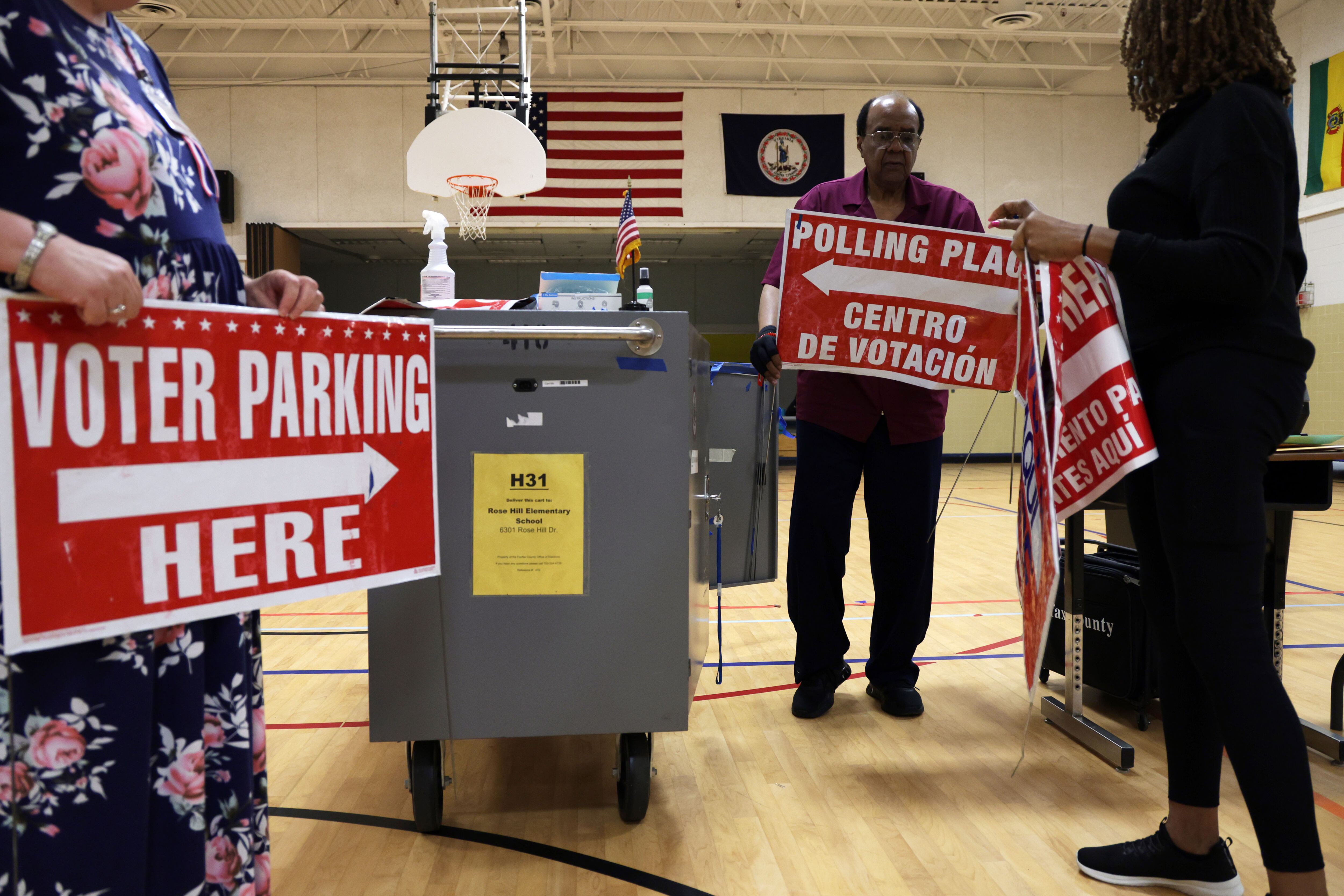

Election supervisors were also able to convince lawmakers to make donations of polling place spaces exempt from the law.

The biggest hindrance under Florida’s ban has been that Earley can no longer use volunteers to help with voter outreach and education efforts, he said.

For example, Earley said, a church would reach out and offer to staff a table with voter registration information if his office sent a staff member to collect documentation.

Now, he said, he can’t accept the free help, which means paying staff, often on evenings and weekends. It “costs more and it’s not as easy to organize,” he said. “Now instead of one person going out and doing it, we need a team.”

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s managing editor and is based in Washington, D.C. She edits and frequently writes Votebeat’s national newsletter. Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org.