This news analysis first appeared in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get the latest reporting from Votebeat and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

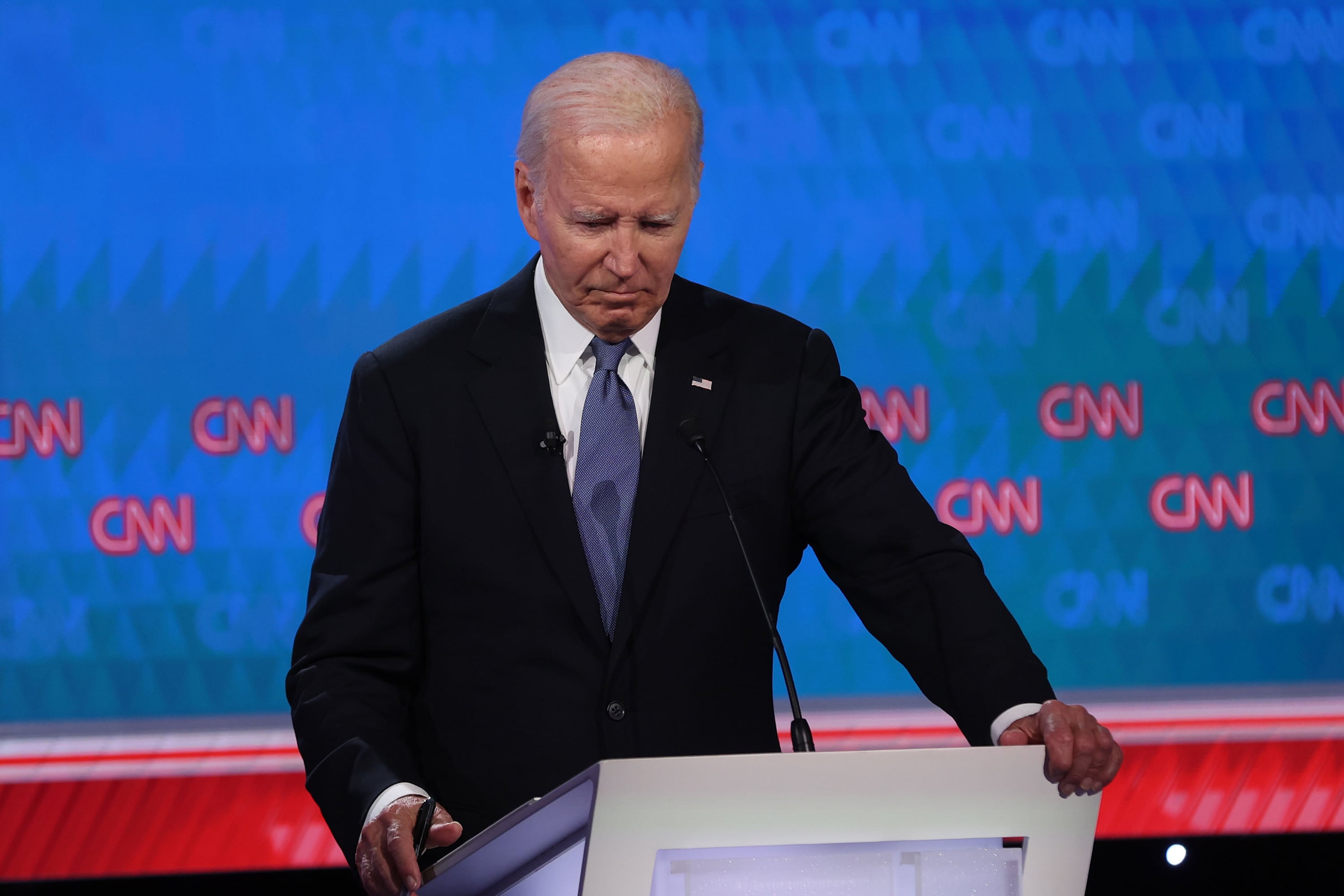

Since President Joe Biden’s poor performance in the first presidential debate, the speculation and arguments about whether he will remain the Democratic nominee for president have been unending. And big questions continue to swirl about what happens if he doesn’t. Can he still be replaced on the November ballot despite locking up thousands of delegates in the Democratic primaries? Who would take his place? What would that require? And when must everything be decided?

My head hurts. Yours might, too. I will try to make some sense of the various answers.

NEW: Why Biden’s decision to drop out doesn’t mean a chaotic replacement process

Other news media so far have amply covered the question of how, under the Democratic Party’s rules, Biden could be replaced before the convention (highly doable, if he hands the campaign over to Vice President Kamala Harris) or at the convention (very unlikely, unless he willingly exits). As always, the party is entitled to choose its nominee by its own processes, though it’s hard to imagine a scenario where it chooses someone other than Biden if he doesn’t voluntarily step aside.

But looking deeper into the world of elections, we still wanted to know: How late is too late to replace Biden’s name on the ballot?

The answer, as with most things in election administration, is that it depends on the state. It’s hard to point to a single clear deadline, but one thing is clear: The logistics of replacing Biden on the ballot become harder the longer the party waits.

The conservative Heritage Foundation has announced it will sue if Democrats replace Biden. Several experts have said that if the switch happens soon, such a suit would have little chance of success: Biden isn’t the official nominee until after the convention, and there’s nothing stopping the delegates there from selecting someone else.

Every state’s deadline, and the basis for that deadline, is a little bit different, but Richard Hasen, a professor of law at UCLA and the director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project, says “the official nomination” is the key trigger. The Democratic Party’s convention concludes on Aug. 22, which leaves the party with a few weeks to consider its choice.

If Biden were to step away after the nomination, Democrats must “turn to the rules that apply for when a vacancy exists,” Hasen said. “And it gets dicey.”

While there’s some precedent in a few states for late changes to ballots, they do have to be proofread and printed, and there are hard deadlines to get that process done in time for the election. That means “there is a point where it’s too late, and then the question is how you count the votes cast for Biden,” Hasen said.

In other words, at some point, Biden’s name simply has to go on the ballot as the Democratic candidate. Even in states without mail voting, ballots for overseas and military voters go out weeks in advance of Election Day. Once they are printed, there’s really no changing them.

If Biden withdraws after the ballots are printed, and Democrats name a replacement who would receive the votes cast in his name — that’s what’s happened in past instances when candidates for other offices have withdrawn or died late in the process — the Electoral College could come into play.

When we cast our votes for president, after all, we aren’t really voting for the candidate. We are voting for a slate of electors pledged to that candidate. In states that allow it, those electors could plausibly choose someone other than Biden even if “Joseph R. Biden Jr.” is the name on the ballot.

But given recent scandals over electors trying to cast ballots for someone other than the chosen candidate, this comes with its own set of potential issues.

To illustrate the slight differences among states, I asked our reporters to figure out how this would work in the states they cover, most of which are highly contested swing states. Here’s what we know:

- Arizona: A spokesperson for the Arizona secretary of state said the office would permit a new presidential candidate until Aug. 30, a date he said was a bipartisan consensus. But the answer may vary by county. Maricopa County says that its ballots need to be finalized by Aug. 22. The state doesn’t bar electors from casting their ballot for someone other than the nominee.

- Michigan: A spokesperson for the secretary of state’s office said that the names on the ballots are those chosen by party conventions, and this step must be done “no later than 60 days before the election so ballots can be delivered to military and overseas civilians 45 days before the election.” The state requires electors to cast their ballots “for President and Vice President appearing on the Michigan ballot.” Electors who do not follow that requirement are disqualified and replaced.

- Pennsylvania: The secretary of state’s spokesperson told us that Pennsylvania law has few legal restrictions on when presidential candidates are finalized for the ballot, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t necessary time limits. The state’s election calendar shows that the state must notify counties of the names of candidates no later than Aug. 27. As in the rest of the country, military ballots would go out shortly after. The deadline for printing and sending mailed ballots to voters who requested them is Oct. 22. The state doesn’t bar electors from casting their ballot for someone other than the nominee.

- Texas: Counties manage the printing of their own ballots, and include the names of the candidates given to them by the secretary of state. That office sends those names in late August, after the conventions. Military ballots, though, go out on Sept. 21, and must be printed days ahead of that. Trudy Hancock, the election administrator in Brazos County, told us the county’s ballots are typically finished by Sept. 10 to allow for proofing and to account for any delays. A 2023 update to Texas’s election code requires electors to sign an oath that they will vote for the chosen candidate. Those who defy the oath are replaced.

- Wisconsin: State law requires that electors cast their ballots for the candidate of the party that nominated them unless that candidate is dead. In a memo, the Wisconsin Election Commission made clear those names would be certified by the major political party state or national chairs to the Wisconsin Elections Commission “no later than 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday, September 3, 2024.” All ballots are distributed to municipal clerks by Sept. 18.

Of course, as the Heritage Foundation has already made clear, Republicans would make replacing Biden on the ballot as challenging and expensive as possible. In addition to the lawsuits Heritage is threatening to file, there are some signs that lawyers are looking to campaign finance law as grounds for a challenge.

Democrats must consider what would become of the tens of millions of dollars the Biden campaign has raised. The consensus among many campaign finance lawyers is that the money cannot legally be transferred directly to a replacement presidential nominee — unless that candidate is Harris.

But at least one prominent Republican campaign finance lawyer is suggesting the money couldn’t even be legally transferred to Harris until after the two are officially nominated at the convention. The promise by such political heavy-hitters to challenge any transfer before that suggests Republicans see it as advantageous to delay a replacement, as the election administration logistics grow more challenging.

It might seem frustrating that a debate about replacing the nominee is happening in only one party, when the other party’s presumptive nominee, Donald Trump, is a twice-impeached convicted felon facing multiple other indictments, including for allegedly trying to subvert the democratic process through fraud. Questions about a candidate’s fitness for office also apply to him.

Republicans did have a conversation — both quietly and in public — about replacing Trump as the nominee in 2016, when the “Access Hollywood” tape went public. But after his victory that year, and his sweep of the primaries this year, Republicans aren’t seriously having that conversation now. Democrats, for better or worse, are having this conversation, and out loud.

As of this week, Biden is insisting he will remain in the race, though intraparty pressure on him to exit is growing rapidly. None of the scenarios we’re talking about may come to pass. But if they do, we’ll be writing about what comes next and what it means.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.

Votebeat reporters Natalia Contreras, Jen Fifield, Alexander Shur, and Carter Walker and Votebeat Managing Editor Carrie Levine contributed.