Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

President Biden’s Sunday announcement that he would step aside as the Democratic nominee for president sets off a frantic decision-making process for the Democratic Party, which now must navigate everything from intra-party politics to campaign finance law to settle on his replacement by the conclusion of its national convention in August.

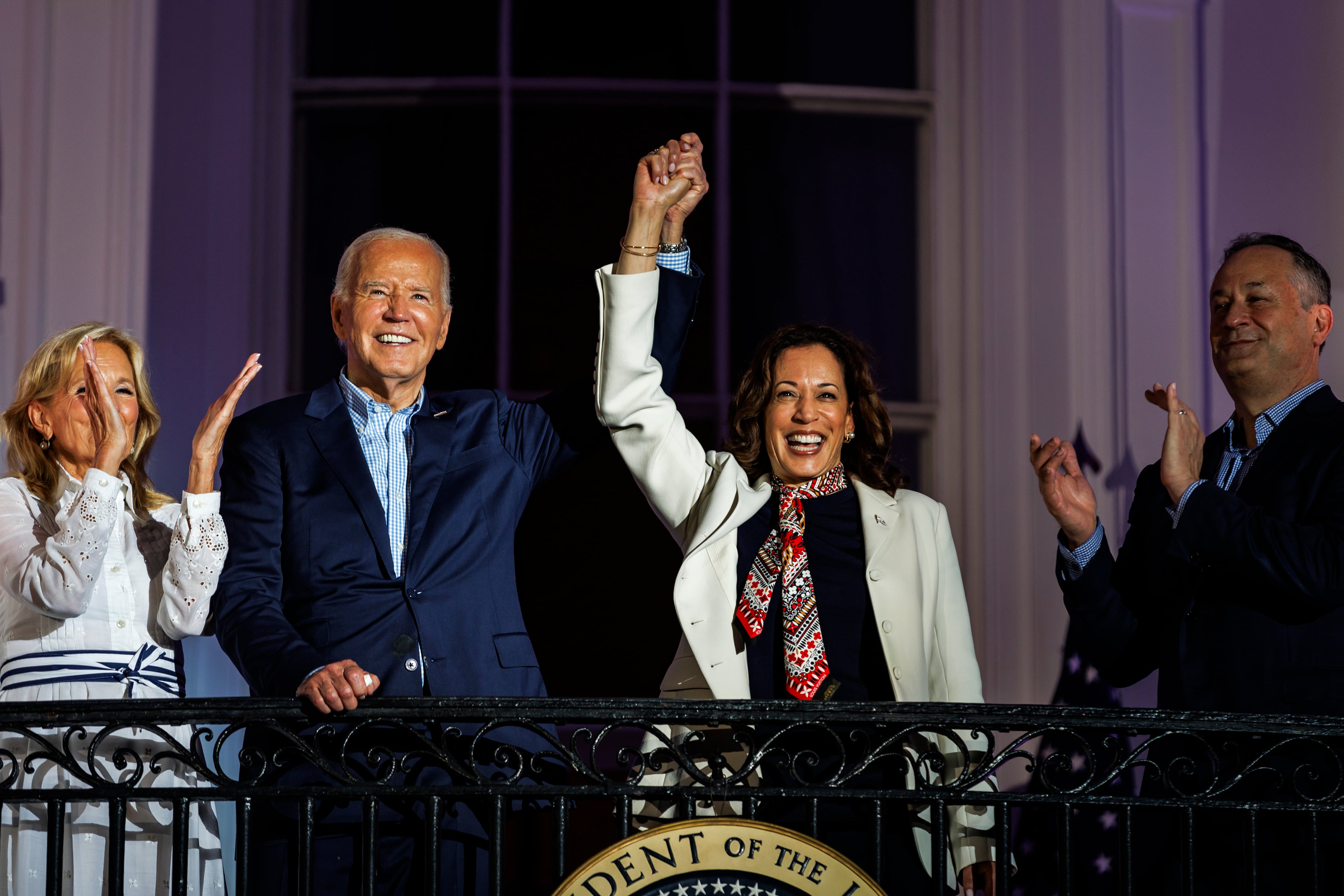

With one month to go, the timing of Biden’s exit and his endorsement of Vice President Kamala Harris to succeed him means the party could seal up the matter and move forward on a normal election schedule, without throwing any voting procedures into chaos — despite legal threats by Republicans to disrupt the nomination.

“Biden wasn’t officially the nominee, and he’s still not the nominee,” said Joshua Douglas, who teaches election law at the University of Kentucky College of Law. “There is no viable way to force his name to be printed on the ballot.”

Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Marymount University Law School, said on social media that while it is entirely likely that Republican partisans will file suit in an attempt to do so (“because we live in an age where people file laughably stupid lawsuits”), judges are unlikely to entertain that argument for long.

The greatest uncertainty is around whether a majority of party delegates will line up behind Harris and provide her a swift path to the nomination during their voting at the Aug. 19-22 convention in Chicago. She technically remains on the same footing as any other candidate that would like to put their name forward.

While certain states “bind” presidential electors to casting their ballot in the electoral college for the candidate selected by the voters in the general election, those requirements do not apply to the party conventions. Presidential primaries are private party functions, and state law is necessarily silent on how they proceed, said David Becker, executive director of the Center for Election Innovation & Research (CEIR). Biden’s delegates, won in the primary, are now uncommitted, and Democratic National Committee rules stipulate that they can vote for who they, in good faith, believe the voters would have preferred.

“They are Biden delegates chosen for their loyalty to Biden,” said Becker, who added that it is hard to imagine a scenario in which they don’t adhere to his wishes.

After Biden endorsed Harris, several major party names — including Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn, and Bill and Hillary Clinton — quickly followed suit. Shortly before 5 p.m. Sunday, the campaign notified the FEC that Harris would now be running for president and changed the name of the campaign committee to Harris for President.

The New York Times reports that Tennessee’s 77 Biden delegates voted unanimously on Sunday to support Harris at the convention. In the five hours after Biden’s withdrawal and endorsement of Harris, ActBlue — a fundraising platform used by Democrats and progressive organizations — announced it had processed $27.5 million from small-dollar donors.

Before Biden exited the race, the DNC indicated it would hold a virtual roll-call vote to shore up support for his nomination. The party has yet to make an announcement on whether this vote will be canceled. If it is, the convention will be an open convention and the delegates will select the party’s nominee there. As long as Democrats end their convention by naming an official nominee, they will meet the states’ deadlines — generally in late August or early September — for finalizing their ballots in time to print them for the start of early voting.

Can Biden’s replacement inherit his campaign money?

Another set of questions for Democrats to navigate is the fate of Biden’s massive campaign fund.

Biden’s campaign committee most recently reported having tens of millions of dollars in campaign cash on hand, fuel for the expensive campaign ahead. Campaign finance lawyers said that if Harris is the nominee, her right to use the money is clear — she’s been on the campaign committee’s paperwork as a candidate for the entire cycle, and the millions of dollars in the account were contributed to both candidates, so there’s no transfer involved.

“I don’t think there is a viable challenge to it,” said Kenneth Gross, a former associate general counsel of the Federal Election Commission who is now a senior political law counsel and consultant at the law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld.

On Sunday, FEC Chairman Sean Cooksey, a Republican, posted on social media an excerpt from a regulation requiring that contributions to a candidate for the general election be refunded or redesignated if the candidate doesn’t run. But Gross and Campaign Legal Center Executive Director Adav Noti, also a former associate general counsel of the FEC, said that would apply only in a situation where neither Biden nor Harris remains on the ticket.

“Every filing since 2020 has designated it the campaign committee of both candidates,” Noti pointed out. “They share a single contribution limit, they share the funds.”

In addition, the regulation Cooksey cites would only apply to the portion of the campaign’s funds raised towards the general election, not the money raised for the primary period, which is still ongoing. In practice, anything an individual donor gave in excess of the $3,300 maximum allowed for the primary election becomes earmarked for the general, because contributors can give up to $3,300 per election.

If someone other than Harris is ultimately the nominee, in addition to refunding contributions given for the general election, Harris wouldn’t be able to transfer remaining money to another candidate’s campaign committee, with the exception of a contribution of a few thousand dollars. In that scenario, the Biden-Harris money could legally be refunded to donors, or transferred to the Democratic National Committee or state parties, or potentially to a super PAC supporting the new Democratic ticket, Gross and Noti said.

That would be less efficient for Democrats — candidates are entitled to lower television advertising rates than super PACs are, so dollars under candidate control go further.

If Harris remains on the ticket as the vice-presidential candidate with a new nominee, Gross said, the situation could be murkier. “If she’s the VP, I think she has a claim on that money, but that would be subject to some challenge,” Gross said. Noti, though, had a slightly different take. “I don’t know why that would be any different from the situation in which she is the presidential nominee,” he said. There are “areas of law here that haven’t previously been explored, but that doesn’t mean that they are necessarily complicated or unclear.”

Both Gross and Noti were bearish on the prospects of any Republican challenge to Harris’ use of the campaign funds, though they acknowledged it’s impossible to anticipate every potential argument. “I have not heard any serious argument to date” that she couldn’t use the money, Noti said.

While there will be inevitable squabbling over the decision among Democrats, Levitt said, and more who may feel cheated after Democratic primary voters supported Biden, he does not believe that will equate to those voters believing there was “intentional manipulation” by the Democratic Party.

“The voters expressed a mammoth preference for Biden. And if Biden were available, that’s what the Dem delegates would be voting for at the convention,” he said. “He’s expressed that he’s not available, and that changed things for everyone, including the voters.”

It hasn’t, though, changed much about how election administrators will do their jobs as the election draws closer, Becker said. With many local primaries still under way, down-ticket candidates for the November election haven’t been determined yet. Election administrators won’t “even start thinking about printing ballots” for another several days.

Douglas agrees. “This changes nothing for election administrators,” he said. “They can proceed as normal.”

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s managing editor and is based in Washington, D.C. Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas.