Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S.

This news analysis was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

After weeks of presidential election drama over everything from a candidate withdrawal to an assassination attempt, the real fireworks at the National Association of State Election Directors conference in Minneapolis this week were over ... snail mail.

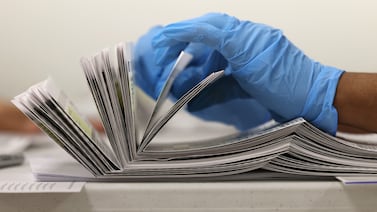

Frustrated election officials raked a U.S. Postal Service representative over the coals Tuesday, telling him that his agency hasn’t been delivering ballots on time, and the situation isn’t improving enough despite repeated requests.

“You have to be better. The actual elections are being determined by these delays,” Bryan Caskey, Kansas’ election director, told Steve Carter, the USPS official in charge of election and government mail programs.

Members of NASED gather like this twice a year, and this time, with the presidential election looming, operational concerns over mail voting were top of mind for nearly all the attendees. These are the people who know election administration best, and if this is what they’re worried about, everyone should start paying attention.

Carter didn’t have specific answers to many concerns election directors raised — or at least didn’t provide the answers they were looking for.

For example, he said he didn’t know exactly when the Postal Service would begin enhanced service to bolster election-related mail delivery. He also repeatedly told the election directors to contact local USPS customer relations staff, even though election officials said those workers’ answers were often insufficient.

Carter said the USPS has improved in some areas, and cited numbers to back that up. Over the 2022 midterm election, the Postal Service delivered 97.3% of “identifiable and measurable ballots” to voters on time, a report from the USPS Office of the Inspector General found. That’s better than in 2018 or 2020, and 6 points higher than the target rate, the report said.

Caskey said while that uptick is “awesome,” it still leaves a significant proportion of improperly delivered or undelivered ballots, which threatens to disenfranchise voters.

Hypothetically, Caskey said, a jurisdiction that sends out 100,000 ballots and has a 95% on-time rate still has “5,000 pissed off, angry voters that are mad about the mail service.”

Election officials also criticized the Postal Service’s plan to wait until late October — a week or two before Election Day — to begin a series of election-related measures including extra deliveries, Sunday collections, early ballot pickup, and the creation of special post office lines for postmarking ballots.

“Why are we waiting till late October?” New Hampshire’s election director, Patricia Piecuch, asked, noting that ballots go out to voters weeks earlier than that.

Carter said the organization tries to keep normal processes in place for as long as possible.

“The extraordinary measures are dedicated for when we view the peak activity of ballots getting through the system,” he said.

Sensing Piecuch’s doubts, Carter offered to talk to her separately about what she’s experiencing in New Hampshire.

Election officials repeatedly raised concerns about mail delivery around the 2020 election, and a federal judge later found that some changes made by U.S. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy contributed to a slowdown of mail delivery during the period leading up to the 2020 election. DeJoy, a former logistics industry executive and major Republican donor, was appointed by former President Donald Trump, who has been a vocal critic of mail voting.

But the concerns now come from jurisdictions across the country. A group of 18 senators, all Democrats, this month sent DeJoy a letter asking for more information about his plans to ensure timely mail delivery.

Washington, D.C., Board of Elections Director Monica Evans said that for one recent election, she never received her own ballot in the mail. She reached out to the USPS staff, and “they kept searching. And there was never any answer,” she said. “They just said, ‘Well, you need to request a new ballot or vote in person.’”

That was easy enough for Evans, she said, since she works in elections. But for other voters, that could have been the difference between being able to cast a ballot or not.

Elections directors told us they’ll keep pressing the Postal Service for answers, but understand that such a large and under-resourced organization may not change quickly.

Votebeat Editorial Director Jessica Huseman contributed. If you work in elections and have similar concerns about USPS delivery times heading into election season, we want to hear about them. Reach out and let us know.

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.