Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Pennsylvania’s free newsletter here.

New rules in Georgia governing how local officials finalize vote totals have some election watchdogs worried that loyalists of former President Donald Trump could trigger a crisis if he loses the state in November, by abusing their authority to delay or avoid certifying results.

Election experts say they’re confident that the system’s checks and balances will quash those efforts and that each state has the legal authority to force members of county election boards to fulfill their duty to certify results. But they and state election officials are still concerned that the attempts could push the process close to strict deadlines and stoke doubts about the integrity of the election.

While the rule changes have put Georgia in the spotlight in recent days, several other swing states are also bracing for battles over the administrative process known as certification.

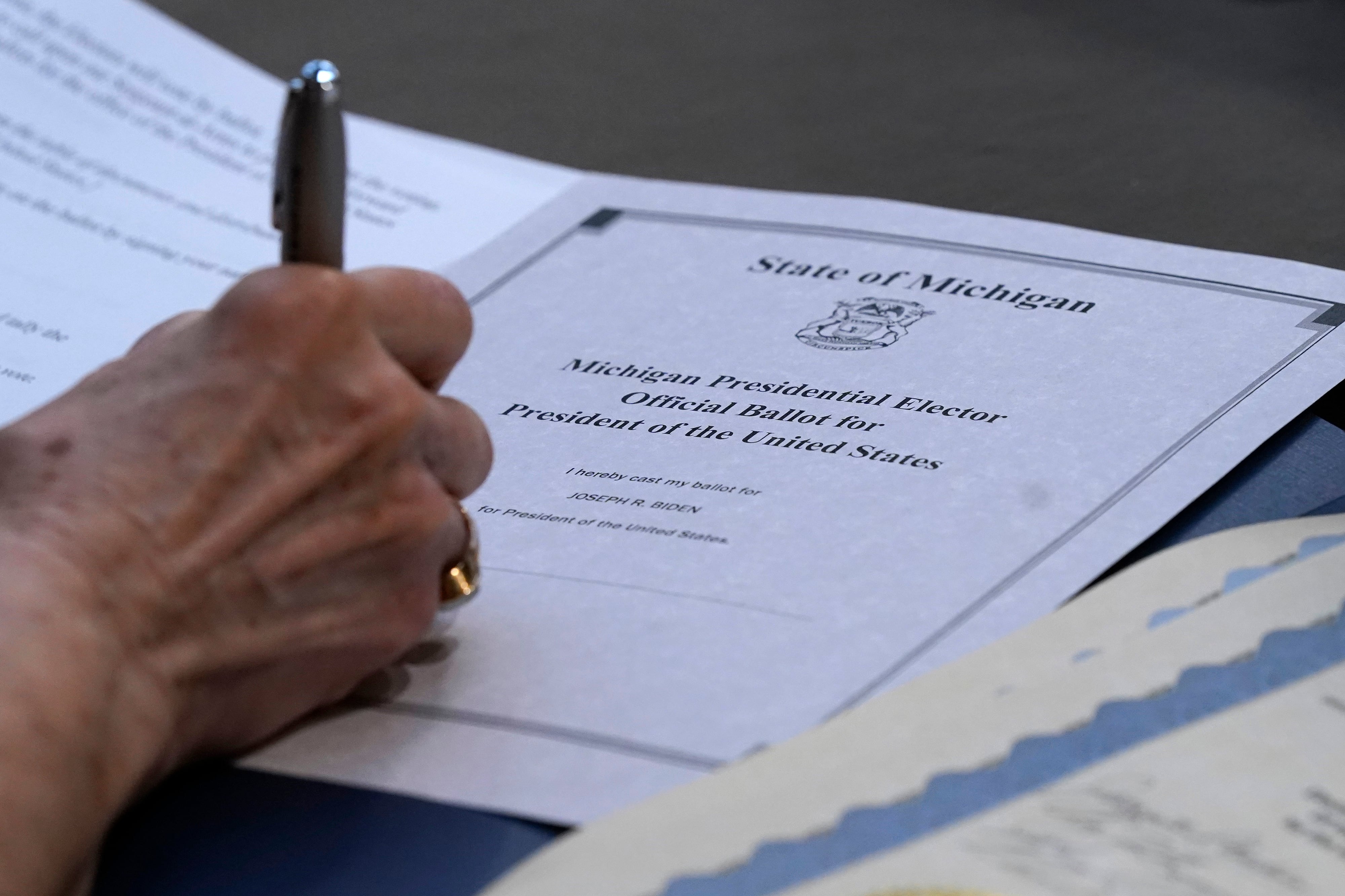

Each state handles certification differently, and the process used to be a routine part of election administration that took place mostly behind the scenes after votes were cast. That changed after the 2020 presidential election, when some Republican members of Michigan canvassing boards initially refused to vote to certify the results amid challenges from Trump, though they ultimately did so.

Since then, some local officials in states including Georgia, Arizona, Michigan, Nevada, and Pennsylvania have declined to certify elections, often at heated public meetings packed with people airing unsupported conspiracy theories or baseless allegations of election fraud.

In every such case, after intervention by state officials or the courts, the election was certified.

Several swing states, including Arizona and Michigan, have taken steps since 2020 to explicitly clarify that local officials cannot legally refuse to certify election results, and to spell out potential consequences if they try, including criminal charges.

But experts say that contentious certification processes erode trust in elections, and they’re wary of rule changes, such as the ones in Georgia, that could be used to justify delaying or refusing certification.

“I think courts are equipped to handle this,” said Derek Muller, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame who specializes in election law and has blogged about the changes in Georgia. “The problem is really foaming up the public anger and dissension.”

Nathaniel Persily, a Stanford University law professor who specializes in election law, agreed. “I don’t think this particular problem is an unsolvable one or one that the courts are unable to address, but it’s emblematic,” he said. “The fact that we are even talking about it as a possibility tells you about the multiple fronts on which the war for a secure election is being fought.”

Peter Bondi, the managing director of Informing Democracy, a nonpartisan, nonprofit election watchdog group, said he believes that changes Congress and some states have made since 2020 have strengthened safeguards, but there is a “strong movement and a growing movement to try to bend the system.”

Informing Democracy is monitoring states, specifically Wisconsin and Michigan, for late changes, but Bondi said he believes Georgia is the only state considering large-scale changes at this point.

Because the rules around certification and the state-local power dynamics vary from state to state, Votebeat’s journalists examined what has happened since 2020 with election certifications in key states, and how well states are prepared to enforce proper certification in 2024.

Georgia: Rule changes raise prospect of delayed certification

Democrats and election watchdogs say two rule changes this month by the Georgia State Election Board appear to be partisan efforts that threaten to sow doubts about election integrity.

The board includes three members whom Trump has personally praised. With those three votes, the board adopted a new rule this month that said local officials should certify that the results are complete and accurate “after reasonable inquiry,” but it did not define what constitutes a “reasonable inquiry.” Muller and other experts said that introduces ambiguity into an otherwise straightforward process.

This week, the board voted 3-2 to adopt a separate rule saying members of county election boards “shall be permitted to examine all election related documentation created during the conduct of elections prior to certification of results.” The new rule also requires county boards to meet and verify vote counts before the deadline for certain types of ballots to be accepted or processed.

The rule also appears to give the board a new investigative role, saying that in any precinct where the number of ballots exceeds the number of unique voters, the board “shall investigate the discrepancy.”

The rule says that if any error is discovered “that cannot be properly corrected, the Board shall determine a method to compute the votes justly.”

Board members who supported the new rules said they will help ensure election integrity. “If the board or the superintendent found that there were votes that were made illegally, they should not be counted,” said one board member, Janice Johnston, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

But election fraud is rare, and some election officials noted that once a ballot is cast, it is impossible to tell who cast it, leaving them no way to pull an illegally cast ballot from the count.

Minor discrepancies between ballot counts and voter totals are not uncommon, and typically aren’t a sign of malfeasance.

The rule echoes a court case filed earlier this year by Julie Adams, a Republican member of the Fulton County elections board. Adams refused to vote to certify the results of two primary elections, saying she had not been permitted to fully examine election records and confirm the results to her satisfaction. She is now seeking a court ruling that would affirm her right to see such records.

State officials and local election administrators opposed both of the new rules, to no avail. Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, said in a statement that the board was engaged in “activist rulemaking” that would “delay election results.” The Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Election Officials submitted comments opposing the proposals and, in the case of the second rule, arguing that it didn’t align with existing legal deadlines.

On Tuesday, the association, which has more than 500 members statewide, implored the state board to stop changing the rules this close to an election. “In a time when maintaining public confidence in elections is more important than ever, making changes so close to Election Day only serves to heighten concerns and fears among voters,” it said in a press release.

Rick Pildes, a constitutional law professor at New York University’s law school and a specialist in legal issues concerning democracy, said he thinks there’s likely to be a lawsuit challenging the new rules, to “get clarity from the Georgia courts well in advance of the election about what Georgia state law does and doesn’t permit or require of these county boards.

“It’s ultimately state election law that is going to determine what power and limitations these county boards operate under,” he said.

Joseph Kirk, the elections supervisor in Georgia’s Bartow County, said he isn’t as worried about the rule allowing a “reasonable inquiry” because he always investigates any discrepancies and provides his local board with explanations and a report between the election and the certification vote.

But the rule passed this week requires each county board to meet by 3 p.m. on the Friday following Election Day to review vote totals by precinct and method cast, Kirk said. That’s earlier than an end-of-day Friday deadline to determine whether to count provisional ballots, accept any additional verification needed in order to count absentee ballots, and receive military and overseas ballots.

“I’m just confused how they got that 3 p.m. number when it doesn’t align with anything else,” he said.

—Carrie Levine

Arizona: Indictment may influence supervisors considering certification

Arizona found out in November 2022 what would happen if a county board refused to certify its election results by the deadline in state law: A court forced them to immediately certify their results, and they did.

That’s because state law says county supervisors have a non-discretionary duty to certify their county’s results as presented by election officials, unless there are results missing. Even then, they can delay the certification only for a short period of time. If a county refuses to approve its results this year, a judge will again force it to, said Phoenix-based election lawyer Andy Gaona.

“There is no serious dispute about (the law), so the courts may again have to serve as the ‘backstop’ against a county that chooses to go down that dangerous path,” Gaona said.

In an attempt to fortify the law, Secretary of State Adrian Fontes in December added a new rule to Arizona’s election manual.

The rule states that if a county doesn’t send its certified results to the Secretary of State’s Office by the deadline for the secretary to certify the statewide results, the secretary must proceed with the state canvass without that county’s results. This could effectively disenfranchise an entire county’s voters. It’s most likely this would affect voters in conservative counties, where Republicans control the boards and where recent efforts to block certifications have been debated.

Republican legislative leaders have sued Fontes over this rule and others. They told a judge that the supervisors’ duty to canvass “does not require it to blindly accept the returns if legitimate concerns are present” and that Fontes does not have the authority to canvass without a county’s results. The judge heard the case this spring and has yet to issue a ruling.

Also pending are the ultimate consequences for the two Republican supervisors in Cochise County, Tom Crosby and Peggy Judd, who voted to delay a certification after the 2022 midterm election. In November, a state grand jury indicted them on charges of conspiracy and interference with an election officer. The trial in that case isn’t expected until after the election, in early 2025.

Still, the case may influence supervisors considering how to approach certification of their election results in November, Gaona said.

“I think it’s safe to assume that the pending criminal charges against Supervisors Judd and Crosby will be on the minds of those county supervisors who are debating whether to play games with their county’s canvass,” he said.

Indeed, in Pinal County this month, Supervisor Kevin Cavanaugh voted to certify the county’s primary results even though he said he didn’t believe they were accurate, telling Votebeat later that he feared prosecution if he voted no.

Cavanaugh also said he was voting yes “under duress” — and the legal implications of that type of vote have not yet been explored.

— Jen Fifield

Pennsylvania: Delays in certification cut close to deadlines

Pennsylvania has faced a number of delays in certifying its elections in recent years, fueling concerns that protracted certification disputes could cause the state to bump up against or possibly miss the new federal deadline for certifying presidential results.

Following the May 2022 primary, three counties engaged in a dispute with the state over certifying their results that took two months to resolve. Berks, Fayette, and Lancaster counties originally refused to include mail ballots that lacked a handwritten date on the return envelope in their certified results, despite a federal court ruling that the date was immaterial to a voter’s eligibility, meaning the ballots should be counted.

The Pennsylvania Department of State sued the counties, and eventually got a court order compelling the counties to certify new results including those ballots.

Then, after that year’s midterm elections, precinct-level recount petitions delayed certification in some counties, which in turn delayed the state’s certification until Dec. 22.

During the primary this April, a Republican lawsuit in Centre County, home to Penn State University, delayed the state’s certification more than a month after the election.

If delays of the same length were to occur in this November’s election, the date of state certification would fall two days after the new Dec. 11 deadline for certifying presidential results.

The Department of State, however, is confident the state will meet its certification deadline for Electoral College votes this fall. It said that the situation in Centre County was resolved in a “timely manner” and that it is confident the judicial branch will “faithfully fulfill its duty to expeditiously resolve post-election disputes.”

“Pennsylvania is prepared for this election, and voters should have the utmost confidence in the electoral system,” press secretary Matt Heckel said.

The department did not respond to a question from Votebeat about whether it was prepared to again take legal action against counties that refuse to certify. But in a statement in May to radio station WITF, Deputy Secretary for Elections Jonathan Marks said the department would be monitoring court cases and “take whatever action is appropriate.”

A bipartisan bill that passed the state House in July — and awaits action in the Senate — would help firm up Pennsylvania’s certification timeline. That would mitigate the risk of missing the new federal deadline for presidential certification, said Marian Schneider, senior voting rights policy counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania.

Certification has also been a concern for the ACLU, one of the most active groups in election litigation in recent years.

“I definitely think counties refusing to certify is a risk in the fall,” said Marian Schneider, senior voting rights policy counsel at the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

She noted certification is not a discretionary act for county commissioners, and that the ACLU was prepared to step in to help litigate a certification dispute if necessary.

“The ACLU is ready and willing to protect the rights of voters,” she said.

— Carter Walker

Michigan: State set safeguards after 2020 debacle

In Michigan, state law requires that county canvassers certify elections. It’s not a matter of choice — it is a requirement of the job, one that carries a potential misdemeanor charge of “willful neglect of duty” for anyone who refuses to do it.

Each board of county canvassers in the state is made up of four people, two Republicans and two Democrats. They have 14 days after an election to certify the results, although it is often done earlier than that.

State law makes clear that results must be certified based only on a review of the compiled voting totals themselves, without regard to anyone’s concerns about potential wrongdoing or the legitimacy of the election.

If canvassers at the county level fail to reach a majority vote to certify the vote within 14 days, they’re then required to turn over the results to the Board of State Canvassers, who are also required to certify the results. A county that failed to certify would have to pay for that state-level canvass, and state officials have made clear those expenses can be passed on to the canvassers themselves.

Those mandates are a change in Michigan, where in 2020, Republicans on the bipartisan Wayne County Board of Canvassers initially declined to certify election results. Later reporting from The Detroit News showed that Trump had personally pressured the county canvassers to not certify the results, which showed Joe Biden winning. One Republican member on the four-person Board of State Canvassers also resisted certification in 2020, citing concerns about the election in Detroit and elsewhere.

Michigan largely defanged future attempts to refuse certification in 2022 when nearly 60% of voters approved Proposal 2, a large-scale expansion of voting access in the state at the constitutional level. Proposal 2 is best known for extending early voting access as well as the right to be a permanent absentee voter who automatically receives a ballot each election. But the constitutional amendment also made clear in the state’s laws that only election officials, not canvassers, can audit elections. It also established that canvassers are required to certify results based only on the compiled voting totals, documents known as “certified statements of votes.”

Even with new laws, though, certification disruptions continue. As recently as May, two Republican county canvassers initially refused to certify a county commissioner recall election, as advocates called for a hand count and forensic audit. The Delta County clerk told CBS News that there were no irregularities, and canvassers eventually did certify after pressure from the state, but the threat remains.

An analysis from The News earlier this month found that 55% of the current county canvassers were not in that position back in 2020, and nearly two-thirds of Republican canvassers are new. Officials have expressed concern the change might mean that despite the potential penalties, canvassers loyal to Trump may again try to block certification in the state if he does not win it.

State officials have made clear that the statute does not allow that. After the Delta case, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and Attorney General Dana Nessel issued a joint release reminding canvassers of their ministerial duty with the elections.

“There is no room for canvassers to go beyond their authority, take the law into their own hands, or undermine the will of Michigan’s voters,” Benson said. “Any canvassing board members that fail to fulfill their responsibilities under the law will see swift action to ensure the legal certification of election results, which will involve significant unnecessary costs for their local communities, along with possible civil and criminal charges against those members for their actions.”

— Hayley Harding

Wisconsin: Law is clear on canvassers’ duties

Unlike some other swing states, Wisconsin has had no instances in recent memory of counties or municipalities refusing to certify elections. And there aren’t any notable murmurings of any canvassing boards preparing to block certification of the November 2024 election.

One reason counties aren’t likely to refuse certification is that state law holds that canvassing boards’ duties are mandatory, said Mike Haas, Madison’s city attorney and the former administrator of the Wisconsin Elections Commission.

“If they refuse, then somebody could take them to court to get a judge to require that the results be certified,” he said.

There are several additional reasons why experts say Wisconsin canvassing boards are unlikely to object to certification, and why any objections that did occur would likely be futile.

One reason is a state law that provides the Wisconsin Elections Commission a path to step in and secure returns from a county that fails to provide them. Another law allows county officials to step in and get returns from a municipality that doesn’t provide them.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission doesn’t appear to be anticipating any local boards blocking certification.

“We are confident Wisconsin’s local election officials are committed to administering elections in a fair, impartial and efficient manner,” commission spokesperson Joel DeSpain said.

By law in Wisconsin, county canvassing boards must be bipartisan. They consist of a clerk, or in some cases a deputy clerk, along with two other county residents, one of whom must be from a political party different from the clerk’s. That mix could also help keep certification objections from taking hold, said Jeff Mandell, an election attorney and co-founder of the liberal group Law Forward.

“I have every confidence that were this to pop up in Wisconsin, we would get it resolved, and we would get it resolved in time,” Mandell said.

Another reason there appears to be little momentum behind stalling certification is that under state law, recounts and post-recount litigation constitute “the exclusive judicial remedy” for challenging election results related to an alleged irregularity, defect, or mistake committed during voting or canvassing. Recounts can take place only after a jurisdiction’s canvassing is complete.

“There are sufficient safeguards in Wisconsin’s process for certification to really head off a lot of possible problems,” said Bryna Godar, a staff attorney at the University of Wisconsin Law School’s State Democracy Research Initiative. “There is also a strong tradition and practice of county clerks and other election officials really just being committed to getting their results correct and getting results reported correctly.”

— Alexander Shur

Texas: Recounts create delays

Texas hasn’t seen state or local officials being unwilling to certify election results in recent history, and the state is unlikely to see an effort by Trump supporters to overturn its election results in November, given that Trump won the state by a healthy margin in 2020 and is likely to do so again, in keeping with Republicans’ decades-long dominance in the state.

Increasingly, an obstacle to certification in Texas is delays due to requests for recounts of local races — even in counties that lean heavily Republican.

The Texas Secretary of State’s office did not respond to questions from Votebeat about whether the office anticipates a push to prevent local officials from certifying election results in November.

A request for a recount in Texas doesn’t affect whether local officials can canvass the results. The canvass is mandatory and done during a public meeting by the election administrator and the county commissioners court or by the political party chairs during a primary election. The canvass must be completed no later than the 11th day after Election Day, but no earlier than three days after Election Day — and only after all absentee, overseas, military, and provisional ballots have been counted.

Although a request for a recount does not delay the canvass, according to state law, it does halt the issuance of “a certificate of election and qualification for the office involved” until after the recount is completed, which can take weeks. That’s the document that’s signed by a county or city executive, or party chair, to finalize the outcome of a race and authorize the candidate to take office.

Recounts rarely change election outcomes. A recount of one race doesn’t delay the certification of the results in all other races of an election. But experts say the unresolved challenges create chaos and undermine the public’s trust in the process.

Aside from certification delays due to recounts, another ongoing concern in finalizing election outcomes is an increase in lawsuits challenging the results. An election contest can be filed the day after Election Day – and a runoff election for the contested office cannot be held until a judge makes a final ruling on the election contest.

At least one election contest in Texas, dating back to 2021, has yet to be resolved by the courts — a challenge filed by a conservative group questioning a measure in a constitutional amendment election. Despite the ongoing lawsuit, Gov. Greg Abbott certified the election.

— Natalia Contreras

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s managing editor and is based in Washington, D.C. She edits and frequently writes Votebeat’s national newsletter. Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org .