Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat’s free national newsletter here.

After two apparent attempts on former President Donald Trump’s life, shootings at an Arizona Democratic field office, as well as the arrest of an Afghan national who had planned a terrorist attack on Election Day, the threat of violence has become a fact of American politics. Memories of the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, with gruesome and unprecedented scenes of violence, have also left many Americans fearing what may come this election.

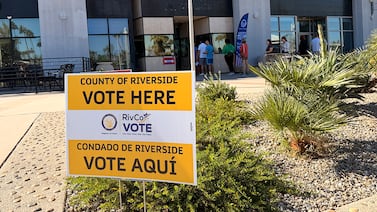

With just weeks until Election Day, it is particularly worrisome to those Americans who will be administering voting. While election administrators have long prepared for the possibility of violence, experts say their concerns have been heightened by the vicious rhetoric and behavior this year.

“Because of this Communist Left Rhetoric, the bullets are flying, and it will only get worse!” Trump said in a post on Truth Social.

The data shows, in fact, that political violence is not at an all-time high for the United States, and that recent incidents have, if anything, diminished support for such action over all.

Still, in May 2024, a survey of election administrators by the Brennan Center found that 40% of respondents had taken steps to increase the physical security of election offices and polling locations since 2020, and 38% reported experiencing harassment or abuse. Across the country, election offices are doing things like investing in “panic buttons” and training poll workers in de-escalation techniques as a result.

“Election officials aspire to prepare for every possible election scenario — sadly, the possibility of violence is one of those scenarios that has been part of election contingency plans and protocols for years, if not decades,” said Tammy Patrick, the chief programs officer for the Election Center, a nonprofit group representing election officials. “What is different this year is the preparation for potential, albeit remote, issues to arise at tabulation centers and election offices over the course of the election, with particular consideration for the post-election period and certification.”

Here’s a look at what election officials in key swing states and their biggest cities are doing to ensure safety this season. Of course, there are limits to what details officials will share about their security plans. The longstanding logic is that if those trying to thwart your security know the outlines of your plans, they can figure out ways around them.

Arizona: Training poll workers to defuse crises

In Maricopa County, Arizona’s largest county, elections department spokesperson Jennifer Liewer told Votebeat that election officials are working closely with the local sheriff’s department, and coordinating with state and federal officials through the county’s command center. “Agencies have been meeting for more than a year to prepare for the 2024 General Election,” she said.

Officials from all levels of government have also participated in tabletop exercises — drills meant to simulate emergency situations so that participants can prepare to respond. The county has also updated its poll worker training to include using de-escalation tactics to defuse potentially violent situations as well as “protocols on when and who to contact should poll workers feel the security of the facility or those in it might have a safety issue,” Liewer said.

“It is our hope that voters will peacefully cast their ballots,” she said. “Poll workers are prepared to intervene and de-escalate situations, but should the potential for violence occur, law enforcement is prepared to respond.”

Michigan: Responding to threats driven by misinformation

Michigan’s election workers have faced high-profile threats and intimidation over the last four years — mostly driven by misinformation.

“People who believe the misinformation have been driven to harass, threaten, or cause harm to local election officials simply for doing their jobs,” said Cheri Hardmon, spokesperson for Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson.

In response, Michigan’s election officials have stepped up their preparation since the 2020 election — hosting tabletop exercises on everything from AI-sparked misinformation to political violence.

“We will be ready — voters should have confidence that we are prepared for any disruption or threats to our system,” Hardmon said.

Hardmon said the state is also working to ensure poll workers feel secure. Benson earlier this year said her office would introduce a direct text line between poll workers and local law enforcement — so-called panic buttons — in response to conversations with election officials as well as emergency responders.

“We cannot have a secure democracy if we do not protect the security of the people who administer our elections,” Hardmon said. “We are very concerned about the potential for those threats to escalate into violence caused by the deliberate spreading of lies about the security and accuracy of our elections.”

Pennsylvania: Task force addressing threats

Earlier this year, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro created an Elections Threats Task Force that includes members in federal, state, and local law enforcement, as well as election administration officials. The group meets monthly to share information and coordinate response in the event of threats. Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt said at a September event that the Department of State had also been conducting tabletop exercises that included what to do if there was a threat of violence at a polling place.

Abigail Gardner, a spokesperson for Allegheny County, the state’s second largest and home to Pittsburgh, said the county elections office is in regular contact with state and local law enforcement about protecting polling places. Poll workers have also been provided instructions on de-escalation tactics. She said the county has not received any credible threats.

Karen Chillcott, Erie County clerk, said the county’s election office has recently tightened its security protocols. Partitions were added in the lobby of the office to separate staff from the public, and windows were installed so that the public could continue viewing ballot counting.

“We’re trying to balance transparency with our security,” she said. Some workers who were on hand for the 2020 protests at the county courthouse are still traumatized from the experience, she said, and the county is already facing increasing pressure from agitators this time around.

She is concerned that the activity might dissuade poll workers from coming to work on Election Day. Threats against election workers are “really counterproductive to democracy,” she said.

Texas: Poll workers equipped for quick response

In Dallas County — a populous, Democratic-leaning county in an otherwise Republican state — officials have revamped poll worker training to include more strategies to prevent and respond to issues of voter or poll worker harassment. Their training for poll workers includes de-escalation techniques and gives specific instructions on how to respond to potential threats or reach out to police.

“Every vote center judge is equipped with a smartphone and detailed contact information for local law enforcement, and poll workers are trained to follow a well-defined plan that prioritizes the safety of voters and election staff,” said Nic Solorzano, spokesperson for the department.

As in other states, the county has participated in tabletop exercises that have involved state and local agencies — the Dallas County Sheriff’s office, the Texas Department of Homeland Security, and local and state emergency management — to ensure a coordinated response in the event of an emergency.

Solorzano said that the elections department “remains cautious yet optimistic,” and that despite heightened tensions “our focus is on preparation, not fear.”

“Our priority is that voters in Dallas County feel secure and confident when casting their ballots, and we are fully committed to maintaining a safe and welcoming environment at all vote centers,” he said.

Wisconsin: Arena available for poll worker training

Milwaukee Election Commission Executive Director Paulina Gutiérrez said the state’s largest city has been working with law enforcement since early summer to prepare for the possibility of violence during voting. They have hosted training sessions with their staff, and worked with the federal government to conduct security reviews of voting facilities.

The city also planned to offer two training sessions for poll workers that would include “de-escalation training and how and when to call the police.” For larger trainings, they planned to use the Milwaukee Bucks’ arena, which the team has donated for the cause.

This will only get more focused as the election draws closer, Gutiérrez said.

“This past week, I already had five [discussions] with our first responder partners,” she said in late September.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org. Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org. Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org. Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org. Natalia Contreras is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org. Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.