Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S.

This news analysis was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

The presidential election this year had a quick and decisive result. In its wake, survey after survey is finding that a majority of the public believes the election was fair and the results are accurate. The polling is finding a significant uptick in Republicans’ belief in the results, which is driving the increase.

A majority of the public asserting they have faith in elections is, by any measure, good news. But after the past few years, it’s also fair to ask whether the results would be different if Donald Trump had lost the presidential election — and whether that faith will hold when elections turn out differently.

It’s too early to answer the second question with any degree of certainty. But at a summit on elections held by the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington, D.C. earlier this month, election officials said they continue to worry — about whether the public will continue to believe in elections, about what comes next, about their own personal safety.

And disputes in a North Carolina judicial race suggest prominent political figures aren’t done making allegations of cheating, though it’s less clear how many people still believe it.

In the Tar Heel state on election night, the unofficial results in a hotly contested race for a seat on the state Supreme Court showed the Republican candidate, Jefferson Griffin, in the lead by around 10,000 votes. But then, as election officials in the state’s 100 counties continued to tally qualifying provisional and absentee ballots, as required by law, Democratic candidate Allison Riggs overtook Griffin.

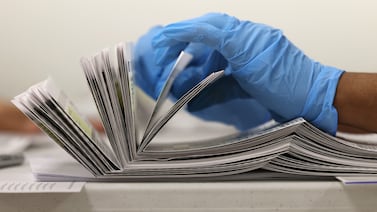

The contest is excruciatingly close. Out of more than 5.5 million votes cast, Riggs ultimately led by 734 votes. An initial machine recount confirmed the margin. A partial so-called “hand-to-eye recount,” designed to discover any potentially meaningful discrepancies with the machine recount, resulted in no substantial change. Separately, Griffin, backed by the state Republican party, has challenged tens of thousands of ballots, and Democrats have now sued to ensure they are counted.

In other words, the results in this closely contested race are receiving every possible level of review from election officials who have been working overtime for months. But last month, Phil Berger, a Republican and the leader of the state Senate, told reporters that “we’re seeing played out at this point another episode of ‘Count Until Somebody You Want to Win Wins,’” in an apparent reference to the tight Supreme Court race.

No one thinks Berger was referring to the presidential race in North Carolina, where Trump was the victor, or, for that matter, his own election, which he won decisively.

And according to the media outlets who reported his comments, he didn’t offer any evidence to support the idea that election officials are doing anything other than exactly what they’re supposed to do — counting legally cast votes.

The executive director of the state elections board, Karen Brinson Bell, decided she had to respond to Berger.

“You are a top leader of our state government. What you say matters,” she wrote to him late last month, asking him to retract his comments. “When you tell your fellow citizens that an election is being conducted fraudulently, they listen. I fear for the people running elections in this state, including in your own community, that some misguided people will conclude from your statements that actions must be taken, perhaps through the use of threats or violence.”

At the Bipartisan Policy Center event this month, Bell said she had little choice but to respond, on behalf of all the election officials in the state, many of whom have been subject to harassment and threats since the 2020 presidential election.

“He has a bigger microphone than I will ever have,” she said. But “just because the other contests turned out the way that he wanted and not this one doesn’t mean that he can attack the very foundations of elections and election officials who are conducting elections according to law.”

For his part, Berger later said his comments were “a reflection of what the general public sees and has concerns about,” NC Newsline reported, and said he has concerns about “the perception that has been created in the public with the situation that somebody’s way ahead on election day, then two weeks later, there’s a different result. I think that creates concerns.”

But suggesting election results were manipulated can turn those kinds of public concerns into public suspicions, or worse. Once that happens, it can take a long time to set the record straight.

Remember “2000 Mules,” the film that alleged that hundreds of people the filmmakers described as “mules” had illegally cast ballots in the 2020 election, resulting in Joe Biden’s victory? The assertions have been unraveling. Way back in June, the distributor pulled the film from distribution and apologized to an Atlanta man who had sued over the film’s false claims that he’d illegally cast the ballots of others.

Now, six months later, Dinesh D’Souza, one of the film’s creators, is also apologizing to the same man, who sued him as well, and acknowledging the film was faulty. True the Vote, the nonprofit group D’Souza credits for the analysis used to support the film’s assertions, said it had no editorial control over the film.

Despite the apologies and the acknowledgement of flaws, both continue to say the premise of the film is true. It isn’t clear why the public should believe that.

More importantly, it’s even less clear whether they do. And whether the public continues to believe poorly supported allegations about the integrity of elections is the most important question to answer.

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s managing editor and is based in Washington, D.C. She edits and frequently writes Votebeat’s national newsletter. Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org.