Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter to get the latest.

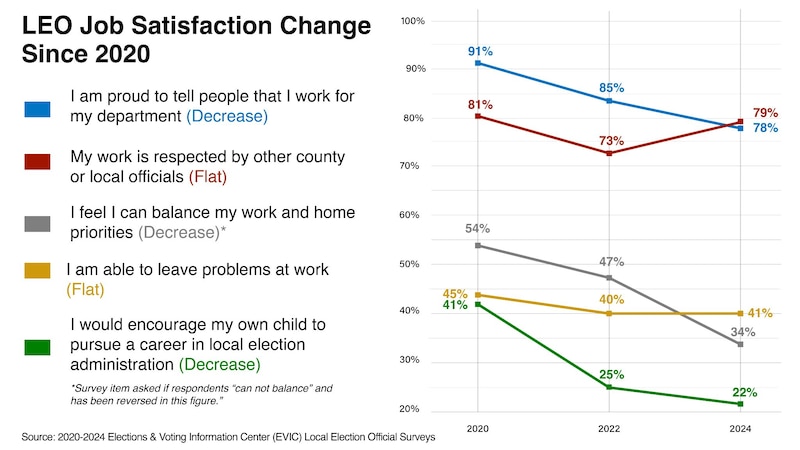

The vast majority of America’s local election administrators would not encourage their children to do the same job, and a shrinking share of them say they would be proud to tell others about their work.

The findings come from a survey conducted every federal election year by the Elections & Voting Information Center, an academic research group. While it contains small bright spots — election administrators largely find the job personally rewarding, for example — the number willing to encourage their children to follow in their footsteps has decreased by nearly half in the past two election cycles. In 2020, 41% said they would do so. In 2024, that number dropped to 22%.

The full survey results will be released next week. The survey was fielded from early August to late October.

The negative outlook on election work continues a trend researchers say they began observing in 2020, when increasing scrutiny, threats, and misinformation fanned by supporters of President Donald Trump began reshaping the profession. Public confidence in elections hit new highs after the November 2024 presidential election — which had a clear outcome despite narrow margins — but election administrators are still pessimistic.

“There are still a lot of cracks in the system, and if things had been closer we would have seen a different reaction,” said Paul Manson, EVIC research director and research assistant professor at Portland State University in Oregon. “Job satisfaction hasn’t gone up — underneath the hood, the people who run elections are still nervous.”

Many election administrators and experts believe the public’s increased confidence in elections is fragile, and would look different if Trump had lost again, if the election had been closer, or if the results had been contested as they were in 2020. After a grueling few years, the survey found, the administrators remain on edge, a finding that could affect whether communities around the country can find qualified candidates for critical election administration positions.

Survey finds a mix of pride and frustration

Paul Gronke, EVIC director and professor of political science at Reed College, said the center began conducting the survey in 2018, hoping to learn more about the field and the people in it, rather than just about how Americans were casting ballots. Until that point, said Gronke, surveys treated “administrators as if they were just cogs in a system.”

In 2020, as the pandemic worsened and Trump intensified false rhetoric against election officials, the survey became a valuable window for political scientists and the media into how election administrators experienced that shift, said Gronke.

Gronke and Manson say they’ve uncovered a strikingly complex picture over the years.

While election administrators express confidence in their own abilities and say they personally enjoy the work, they struggle to leave their problems at the office.

“While many of us in election administration view our jobs as incredibly important, and we value the choices we have made in our lives, we look at the wasteland that is our lives and we think, ‘We wouldn’t want this for our kids,’ because election administration is so hard,” Judd Choate, Colorado’s election director, told Votebeat.

Choate — who teaches in the election administration program at the University of Minnesota and has helped craft questions for the survey over the years — said his own 17-year-old daughter has become more interested in elections, but still has no interest in doing the same job.

“I’m perfectly fine with that,” he said. “Please, become a doctor. Become a lawyer. Be a mathematician. Don’t do this. One hundred percent, that is the way I view this job.”

Training sessions feel ‘like group therapy’

Melissa Kono is the part-time clerk for Burnside, a 500-person town in western Wisconsin. There, clerks are elected members of the town board. It’s a part time job, paying only $6,000 a year. Kono is also a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she teaches courses on community resource development.

For her, the combination makes sense — her professorship pays the bills, and the two jobs align nicely. As part of her work for the university, she travels around the state training other election administrators. But she understands that for many others, the bad is starting to outweigh the good.

“The pandemic and the volume of absentee ballot requests coupled with unnecessary criticism is what has led to this fatigue — just saying, ‘I’m done with this,’” she told Votebeat. “People who I never thought would give up have left their positions because of the pressure and criticism and dealing with irrational people.”

All of the anxiety and pressure have led some of her training sessions to feel “like group therapy,” she said.

The survey also shows that election officials in small counties and large counties have very different experiences. In less-populated areas, officials are far more likely to focus on elections for only a small part of the year, while large cities and counties typically have full-time staff dedicated only to elections. Rural areas also have less of a problem recruiting poll workers.

Perhaps the most striking difference is the impact of the spread of false information. Only about 20% of administrators in jurisdictions of under 5,000 voters reported that misinformation was a serious problem. In jurisdictions of more than 100,000 voters, nearly half report that it is.

Kono said that because Burnside, Wisconsin, has so few voters, they are provided “white glove” service. She can interact individually with anyone who is experiencing a problem — whether that’s cynicism over election integrity or a missing absentee ballot.

“In a rural area, we have the advantage of knowing our neighbors,” she said.

By contrast, Heider Garcia in Dallas County, Texas, oversees voting for more than 1.4 million people. He is paid well for his job, which focuses entirely on voting and elections. His ability to pay his full-time staff a livable wage also makes it easier for him to attract candidates from other fields, which medium and small jurisdictions struggle to do.

Finding the right people for election work is difficult

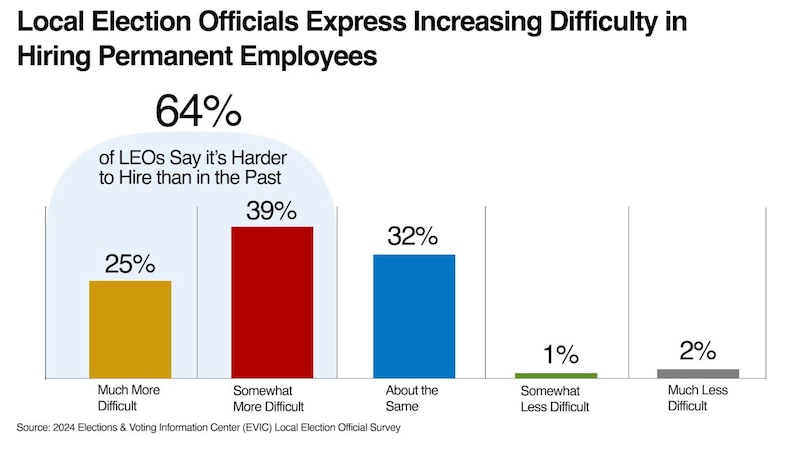

Still, across the board, election administrators say that hiring qualified, full time staff is difficult. As Gronke and Manson have done follow-up interviews with some of the respondents, they learned that low pay, high stress, and intense scrutiny were the barriers.

“We had one election official say they couldn’t compete with In-N-Out Burger on pay,” said Manson. “Administrators want to communicate that this is a long term job with good benefits, but so are other county jobs. And they do not come with as much scrutiny or criticism.”

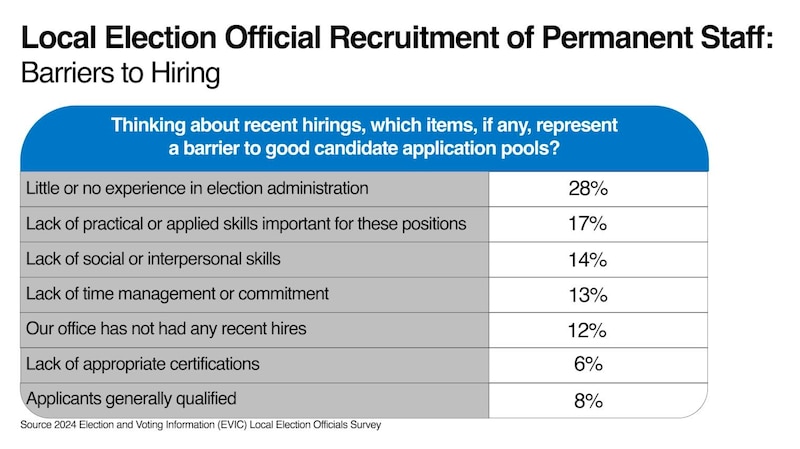

Critically, more than 40% of election administrators say that job applicants have little to no experience in elections, and more than a quarter say that applicants lack the practical skills to do the work. That isn’t surprising in such a niche sector.

“Nobody goes to election school. Nobody says, when they are in high school, ‘Oh, when I graduate I want to go here and study to be an election administrator,’” he said. “It’s more about having the right skills, and then the job comes up.”

Garcia said that people who have experience in event planning or who have run a business tend to have transferable skills. In his previous job, in neighboring Tarrant County, his deputy elections administrator was a former Marine.

“You can learn the business if you have the right skills,” he said. The problem, though, is that the number of necessary skills continues to expand. “We joke. Like, you have to be a lawyer, an IT person, a spokesperson, a negotiator, and an event planner.”

In recent years, the availability of training has improved. The University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Policy — where Choate teaches — offers a certificate in election administration, for example. Choate hopes the industry will start proactively reaching out to more people to attract them to these programs and to the field itself.

Choate said the EVIC report (and others like it) “demonstrate the need for an aggressive program to create education opportunities for young people, people in college and people trying to get into a second career … that set them up for success in the world of election administration.”

Why medium-size jurisdictions struggle

Manson said one thing that stands out to him every year is the struggle medium-size counties experience. “Small counties don’t have that many ballots, and large counties have far more resources,” said Manson. They can usually muscle through, he said.

But for the medium-size, often suburban counties, “it’s like reverse Goldilocks,” he said. Demands are growing as population grows, but resources aren’t necessarily coming in as fast: The buildings are frequently too small, and there is almost never enough staff.

A few markers have been consistent since EVIC began the survey in 2018. Most notably, the demographics of full time staff. Eighty-eight percent say that they are white, far higher than in the population at large. This number is consistent across jurisdiction size. Just under 85% of respondents to the survey were women (though this number is significantly smaller — just under 50% — for larger jurisdictions).

Gronke and Manson say the job of clerk has historically been popular among women, because it used to be a quiet job that allowed you to balance the demands of family and work. The nature of the work is also viewed through a gendered lens. Kono said she and other clerks are often treated “just as the secretary, or just the person who takes the minutes.”

“Yeah, I wish I just took the minutes,” she said. “That is the easiest part of the job.”

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.