Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S.

This news analysis was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

I have been reading federal lawsuits about voting for the better part of a decade, and I am used to being buried in references to things like 52 U.S. Code § 20507(b)(2) or parsing whatever the Supreme Court recently decided Purcell v. Gonzalez means in practice for this election cycle.

This week was different.

Within days of President Donald Trump’s executive order to overhaul election administration, three lawsuits were filed in federal court to challenge it (a multistate coalition filed a fourth lawsuit on Thursday). And unlike the usual dense filings packed with obscure statutory citations, these complaints are startlingly simple. Think “Constitution 101” simple.

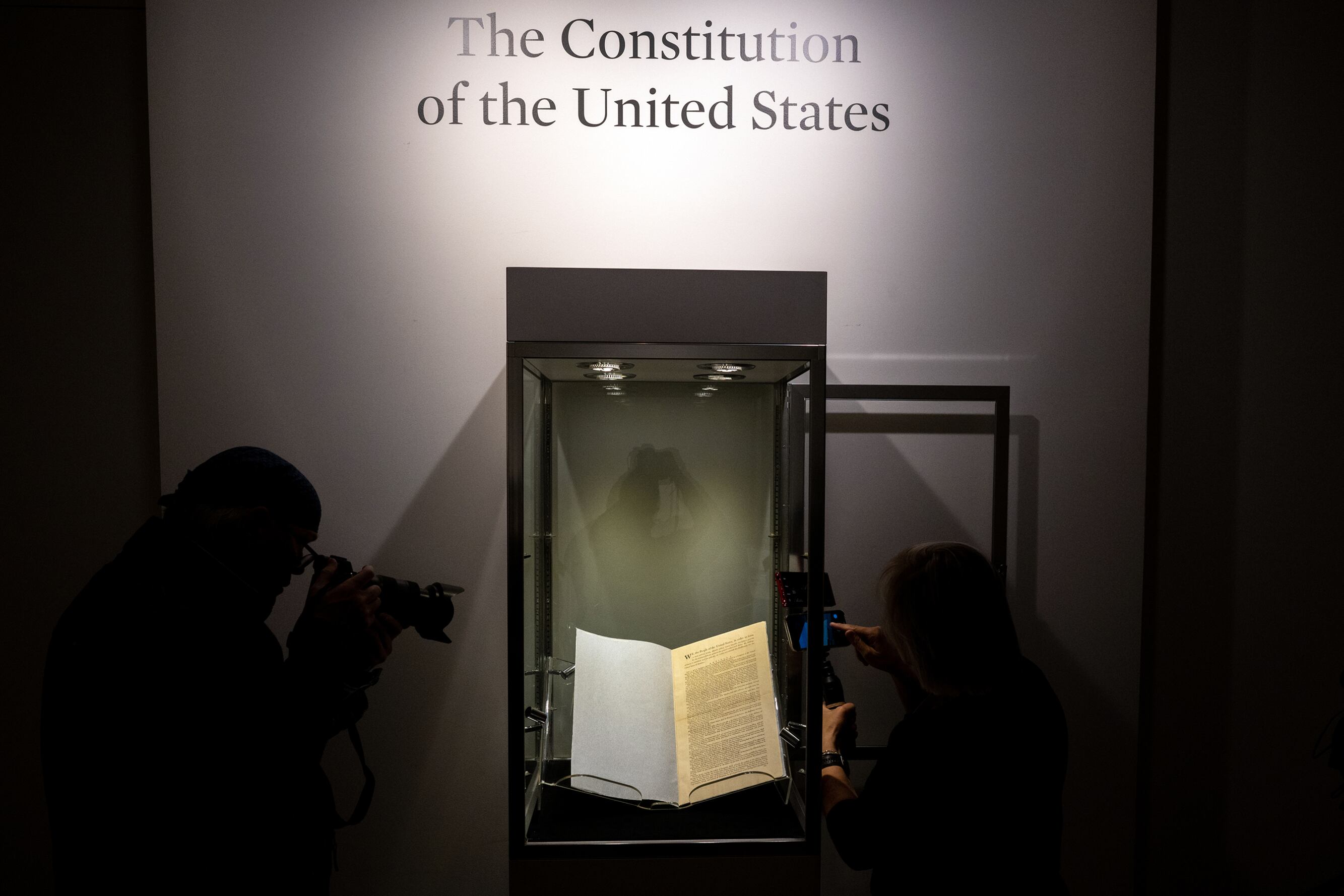

These lawsuits quote the Constitution directly — no bells, no whistles. We’re talking Article I and II, with a heavy assist from the 10th Amendment. These are the kind of things that I used to teach high school debate students, who could argue them with more clarity than some members of Congress. No offense. (Some offense.)

Why such a simple approach? Because the question of whether the executive order is legal is a simple constitutional question.

Trump pitched the order as a way to “secure” elections. But he very clearly attempts to wrest control of election administration from the states and from Congress. That — the complaints all say — obviously violates the Constitution.

“I’m not sure it is more complicated than that,” said Ben Ginsberg, an election attorney who advised George W. Bush’s and Mitt Romney’s presidential campaigns.

Indeed, the Constitution expressly delegates the administration of elections to the states. Article 1, Section 4 gives state legislatures the power to determine the “Times, Places and Manner” of elections. Article 2 does the same for the power to determine how presidential electors are chosen. Congress, too, has authority to regulate federal elections under Article I, but presidents? None. The 10th Amendment makes this even clearer: any power not specifically given to the federal government is left to the states.

“...the Framers’ deliberate assignment of election-related powers and prerogatives is in peril,” reads the complaint filed by Democratic leaders and national party committees. “Although the Order extensively reflects the President’s personal grievances, conspiratorial beliefs, and election denialism, nowhere does it (nor could it) identify any legal authority he possesses to impose such sweeping changes upon how Americans vote.”

Ginsberg said the idea that elections should be left to the states has previously been uncontroversial doctrine in the Republican Party. As recently as last year, for example, Republicans opposed Democratic legislation on elections, known as HR 1, portraying it as an illegal attempt to nationalize elections, even though Article 1 does give Congress power to change election laws.

That legislation also came under fire from election administrators, who said some aspects were impossible, impractical, or too expensive to execute. Still, one of the biggest weaknesses of HR 1 is “repeated in this executive order,” Ginsberg said. Namely: None of the drafters appear to have consulted a single election administrator, and the instructions in the executive order would be hard — if not flatly impossible — to put in place.

Take, for instance, the order’s directive that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and other federal agencies “heavily prioritize” allocating federal funding to states using voting systems certified to the latest possible standards. The catch? Not a single voting system currently on the market meets those standards. In other words, the order sets a bar that’s impossible to reach — ensuring that states are set up to fail from the start.

“Whether you are a MAGA-affiliated, Democrat, or Republican election official, and whether or not you agree with the overall policy goals, it just doesn’t work as a practical matter,” Ginsberg said.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.