As Maricopa County investigates what exactly caused machines to reject thousands of voters’ ballots on Election Day, a Votebeat analysis of technical evidence found that local officials may have pushed the county’s ballot printers past their limits.

The thickness of the ballot paper the county used, the need to print on both sides, and the high volume of in-person voting are all likely to have contributed to poor print quality on ballots, according to Votebeat’s review of printer specifications, turnout data, and interviews with eight ballot-printing and election technology experts.

“It was a cascade of events, and once the first domino fell, they were setting the dominos back up while rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” said Genya Coulter, a senior election analyst and director of stakeholder relations for election technology and security nonprofit OSET Institute.

The poor print quality caused machines to then reject thousands of ballots across the county, forcing voters to instead place their ballots in a secure box to be tallied later. Two technical experts closely familiar with the county’s equipment, who did not want to be named because they didn’t want to get ahead of the county’s public statements, said that the paper thickness was likely a major factor in why the toner — the powder laser and LED printers use to make images on paper — did not properly adhere to both sides of the paper.

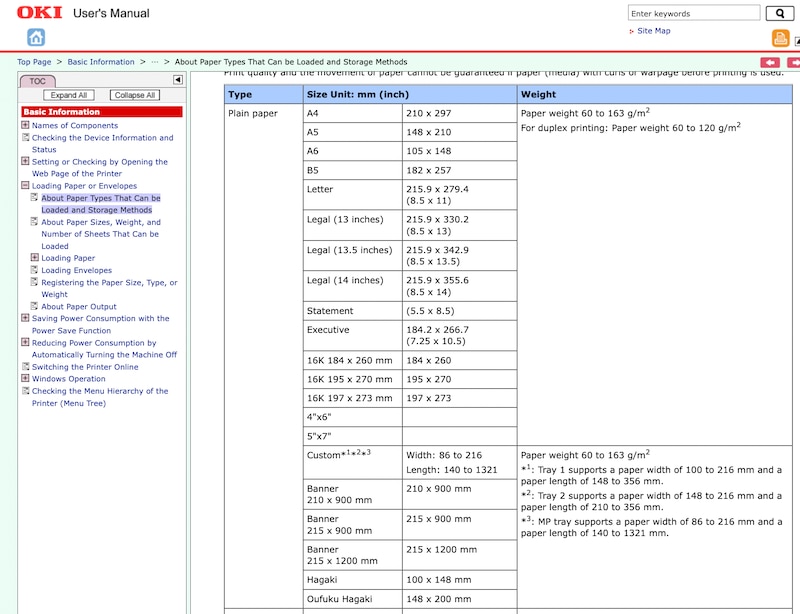

The county used thicker ballot paper than the printer supports when printing on both sides of the page, according to the user manual for the OKI B432dn LED printers. Paper weight of up to 80 pounds is supported, but the county’s ballots were printed on 100-pound paper.

“To perform high-quality printing, be sure to use the supported paper types that satisfy requirements, such as material, weight, or paper surface finishing,” the manual specifies.

The printers’ fusers, which melt the toner onto the paper, could have also degraded by the time Election Day arrived, said Coulter, who along with working for OSET, has advised and trained election workers on technology problems.

One month after the midterm election, Maricopa County election officials have yet to provide a full account of the problem. A detailed explanation could help address claims circulating from GOP leaders, including from Republican gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, that the problems were somehow intentional and aimed at disenfranchising Republican voters. Analysis by numerous media outlets has found the problem did not disproportionately impact Republican-heavy areas.

At least 30% of vote centers had problems scanning ballots on Election Day, which forced about 17,000 voters to put their ballots in the secure box, known as “door 3,” for later counting at the county’s central elections center. The county has emphasized repeatedly that everyone was able to cast ballots. But the problems exacerbated lines in some locations, according to several poll workers.

OKI Data Americas spokesperson Lou Stricklin told Votebeat in an email that it is “up to the elections services provider to test their systems (including the printer) to ensure that the ballot material being used is appropriate for the printer and printing accurately.”

Maricopa County Elections Department spokesperson Megan Gilbertson said that the testing county officials performed before the election confirmed that the printers worked with the county’s ballot paper.

“The Oki B432 printers have been a very reliable printer for the Election Department,” Gilbertson wrote in an email. “Our stress tests performed before and after the election show that printing on 100lb ballot paper in quick succession does not result in lower print quality.”

Maricopa’s testing somehow did not capture the problem. Election technical experts such as Neal Kelley, a ballot-printing expert and longtime former Orange County registrar of voters, say comprehensive testing is key. California is the only state with a state certification program for printers that requires rigorous testing before a county can use a printer, spurring election officials such as Kelley to use a comprehensive process to understand a printer’s capacity before buying them.

County officials first used the printers in 2020 and again in this year’s primary, and they didn’t know what difference could have triggered the problems in the general election. But in 2020, the county used 80-pound paper. And in the primary, the vast majority of ballots, or about 80% of ballot styles, were one-sided, according to Gilbertson. When only printing on one side, up to 110-pound paper is supported, according to the OKI manual.

Why some printers had problems and others didn’t is unclear. It could have to do with the age of the printers or the fusers. The county has only used the printers to print ballots since 2020 but was using them to print ballot envelopes during early voting before that. Of the fewer than 600 OKI printers the county currently has, 20 were purchased in 2017 and the rest were purchased in 2018, Gilbertson said.

Maricopa County officials declined a request for an in-person or phone interview for this story, and instead asked that Votebeat send questions in writing, with Gilbertson citing “lawsuits” as the reason.

“Maricopa County is continuing its root cause analysis to identify why some Oki printers did not print the timing marks dark enough,” Gilbertson wrote. “This is being done while we have been completing the canvass, recount and responding to public records requests and election contests.”

Supervisors Chairman Bill Gates, a Republican, has apologized on behalf of the county and said the problems cannot happen again. He has also acknowledged the importance of conducting smooth elections, especially since the 2020 election brought so much scrutiny onto the county’s practices.

“The eyes of the world are on Maricopa County,” Gates said at a press conference at the county’s election headquarters a few days after the election, surrounded by TV cameras and reporters from around the world.

Gates did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

COVID-19 led to county retrofitting printers

Cascading choices that county officials made over several years – some which were brought on by circumstances outside of their control such as COVID-19 and supply chain problems – contributed to the issues in this election.

As the 2020 election approached, traditional polling places such as schools and senior living facilities declined to operate as polling places for health reasons, so the county decided to make the switch to a new model of in-person voting that required fewer polling places.

The vote center model, which the county tested in part in 2018, would allow voters to cast ballots at any location, eliminating the need for a polling place in each precinct. But because voters could now come from any precinct to any location, and because each precinct has different contests on the ballot, the county needed a way to print any precinct’s ballot on demand.

With hundreds of thousands of voters expected on Election Day, the county needed lots of printers, fast. Meanwhile, the pandemic was also affecting the supply chain, Gilbertson said.

“To overcome these obstacles, the County found a solution to retrofit our printers that had been used to print ballot envelopes and control slips,” she said.

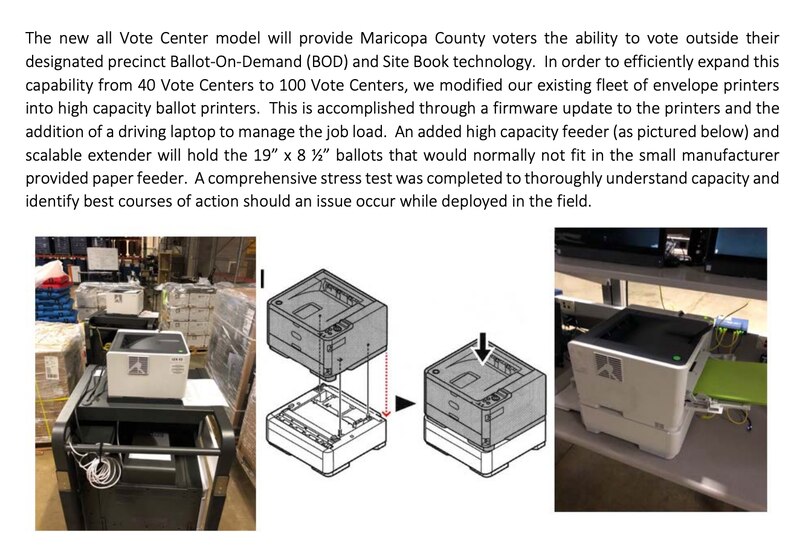

The ballot-on-demand system the county uses is from Runbeck Election Services, and Runbeck was consulted on the retrofitting of the OKI B432s. The retrofit included adding a laptop, updating firmware, and adding a paper feeder to fit ballots, according to the county’s 2020 primary election plan.

The B432’s worked well in 2020, so the county decided to keep them as they replaced the two other types of printers they had been using, another OKI model and a Lexmark. The county purchased 160 new Lexmark printers for $1.8 million last year, Gilbertson said.

For paper, the county was used to using thick paper. Heavy paper is recommended for use in the Dominion scanners that the county has long used to tabulate ballots on site, according to a Dominion technical guide.

In 2016 and 2018, the county used 110-pound paper. The county was renting larger printers, not using the smaller B432s, to print those ballots at the time, according to former Recorder Helen Purcell.

In 2020, 100-pound paper was not available because of paper shortages, county officials said previously. That led the county to use 80-pound paper. At the same time, the county began recommending using Sharpies to fill out ballots, adopting a recommendation from Dominion, because of their fast-drying properties.

That’s part of what caused what’s now known as “Sharpiegate.” The Sharpies bled through the thinner paper at times, causing voters to worry that their selections would not be read properly. Bleed-through doesn’t matter, though, because the ovals on the back are offset.

This year, county officials switched back to the 100-pound paper.

The county used the same printers in the primary that it did in the general this year, except for those that were decommissioned, Gilbertson said. Two factors were different, though: The length of the ballot went from 19 to 20 inches. And only 20% of ballot styles were two-sided in the primary, while all ballots were in the general.

Blake Sacha, a poll worker in Mesa, said his location experienced problems with ballots about an hour or so into Election Day. The line started to really back up at that point, he said. A technician was on site, but they couldn’t figure out what was wrong. Pretty soon, somehow, voters had figured out that if they colored in the timing marks on the ballot, the black lines along the edges that tell the machines where to look for voters’ selections, then the machine would accept the ballots.

“You could tell that, randomly, some of the black squares were not completely filled in,” he said. “Something was incomplete about those black dots.”

Similar systems across the country use thinner paper

The stakes are high for counties that rely on all parts of an electronic voting system to work perfectly in front of the voters’ eyes, from the time the voter checks in to the time the ballot is tabulated.

Much can go wrong in the sensitive system. Electronic poll books with voter registration information can have connectivity problems. The power supply itself can be too weak for the printer to function properly. Humidity can alter the paper quality ahead of time. Tabulators can be programmed incorrectly, causing wide-scale ballot rejection.

Votebeat could find only 10 counties of the 50 largest in the U.S. that print and tabulate their ballots on the spot on Election Day, using research from the National Conference of State Legislatures and Verified Voting. That’s in part because vote centers aren’t legally permitted everywhere.

Printing a ballot is a very precise task, from print quality to paper alignment, considering how sensitive ballot scanners are. And printers are known for their IT headaches.

Jeff Ellington, CEO of Runbeck Election Services, which manufactures the system that Maricopa County and many other counties use, said Runbeck chose which printers to pair with its ballot-on-demand system only after rigorous testing.

While the B432s are widely used for ballot printing, along with other OKI printers, they won’t be soon. OKI discontinued printer sales in the U.S. in March 2021, according to Stricklin, although customer support and parts are still available. Printer parts are typically available for five to seven years after a printer is discontinued, Stricklin said.

“We have not received any technical support inquiries regarding the Maricopa County printers,” Stricklin said. “As I noted above, we continue to maintain a customer support center to assist our ballot partners, or any customers, should they require technical support.”

So if other counties use these printers, why did only Maricopa County have the problem?

Votebeat’s review of similar systems across the country found one main difference: paper thickness. Orange County and other counties in California that are similar to Maricopa County in size and system, as well as many Florida counties, all use 70- to 80-pound paper.

Most counties use 80-pound paper, Ellington said.

The paper thickness matters because of the way these printers work. The fuser inside of the printer heats up to melt toner onto the paper. The thicker the paper, the hotter that fuser has to get, Ellington said. If it doesn’t get hot enough, that’s when you see problems with the print quality. Stricklin did say that a different OKI printer, the C931dn, is able to achieve higher print qualities on thicker paper stocks.

The county and Runbeck’s technical experts, who were deployed early on Election Day, quickly realized that print quality was part of the problem. Because the toner wasn’t properly adhered to the sheet, some was flaking off inside the scanner, affecting that machine’s ability to scan ballots.

Fix doesn’t explain the root cause of problems

By mid-day, the technical team had found a fix that seemed to be working.

Technicians changed the “media weight” setting, which considers the thickness of the paper, for the ballot envelopes and ballot receipt from medium to heavy. The county has said that the media weight setting for the ballot itself was already set to heavy.

It’s unclear why changing the setting for the envelopes and receipts would affect how the ballot was printed. Asked to explain, Gilbertson responded “Our root-cause analysis is still in process.”

The fix didn’t seem to help everywhere, according to Votebeat interviews with multiple poll workers.

Sandi Steele, who served as a poll worker in Surprise, said that a technician came to her location around 2:30 p.m. and changed the setting on the printer. The tech stood there and watched for about 10 to 15 minutes and it seemed to be working fine.

“But once you took your eyes off of it…” she said. “I don’t think the fix solved it as well as they said.”

Steele said the problem kept cropping back up, even after the settings change, and workers were isolating printers throughout the day to try to figure out the problem. The tabulator would take one or two ballots, and then kick one out, she said.

“All of us were throwing out all kinds of theories,” she said.

The setting change seemed to work at Sacha’s location in Mesa, which pleased voters. By about noon, all three printers were up and running.

“When they started taking ballots successfully, people were cheering and happy,” he said.

Cleaning off the toner that had flaked onto the scanners was also crucial, according to a technical expert familiar with Maricopa County’s system. Before the election, the county had trained technicians on how to clean the scanners. That was new this year, in part because the county knew that Republican leaders were encouraging people to bring ballpoint ink pens to the polls, because of Sharpiegate. These pens dry slower than felt-tip pens, gumming up the scanners.

Tara Bartlett, a Democratic Party observer at a vote center in Phoenix, said that her location had problems starting early in the morning. A technician came and cleaned the tabulator, she said, and that helped.

“But I wouldn’t say it solved all problems,” she said.

As the tabulator continued rejecting some ballots, the line at times was past the polling place’s 75-foot boundary, she said. She didn’t know until the next day the county had deployed a printer fix, and doesn’t think that fix was ever implemented at her vote center.

“We had problems up to 7 p.m.,” Bartlett said.

When the county got the roughly 17,000 ballots that had been placed in door 3 back to its central elections center, it found that most of them could be scanned by the larger tabulators there. On nearly 1,600 of them, the county found that voters used ballpoint pens and didn’t properly fill in the ovals to mark their selections, which is why they could not be initially scanned.

High in-person turnout leads to high demand for printers

In-person voter traffic was significantly higher this year than in 2020, although individual vote centers served about the same number of voters because the county increased the number of locations.

The county’s printers served 248,000 in-person voters on Election Day in the November election, compared with 165,000 voters two years ago. In this year’s primary, it was 106,000 in-person voters on Election Day, versus 60,000 in the 2020 primary.

The county uses between two and four printers at each location, based on how busy the location is and the size of the location. A standard polling place has eight check-in stations and three printers. In both the 2020 and 2022 general elections, the busiest locations saw more than 2,000 voters on Election Day.

OKI’s fusers are reliable for up to 100,000 standard one-sided pages, according to the company’s website. The county’s ballots were double-sided and 20-inches long.

Coulter said with such long ballots and high in-person turnout, the OKI printers could have reached their limit.

“[In Maricopa County] if the same two printers were in operation for Election Day and a three-week early voting period, it’s altogether possible that the fuser wore out,” she said.

Coulter said the county should have more printers at each location, and one printer for every voter check-in computer, or e-pollbook. She gave an example from the polling place she led during early voting in Lakeland, Florida, which had four e-pollbooks and four printers for an average daily turnout of 750 or more.

In Orange County, which uses OKI B432s to print ballots on demand, Election Day turnout at each vote center ranged from 113 to 1,336 voters. The county’s ballot is 14 inches long and two to three pages. The county had four printers at most vote centers, with three at smaller locations, according to Bob Page, the county’s registrar of voters.

The county uses 70-pound paper, and replaces their toner before every election.

Kelley said that, in Orange County, the county expected to get somewhere between four to six years of use from the printers before replacing them.

Printing papers with different thicknesses over time, such as ballots and envelopes, can cause damage to the printers, Kelley said, and can cause ballot alignment problems.

“Printing envelopes can be challenging, and cause wear and tear on the printer,” he said.

Mark Lindeman of Verified Voting agreed that printers can lose their reliability over time. That said, he said it’s human nature for us to think that something that works will continue to work.

“I’m sure that election officials will have a woulda, coulda, shoulda,” he said.

Could certification or more rigorous testing have caught the problem?

Lindeman, Kelley, and other technology experts asked whether more rigorous testing could have caught the problem before Election Day.

The county printed dozens of test ballots from every printer before the election, Gilbertson said.

It also stress-tested eight printers, which included printing hundreds of ballots in quick succession and then running them through tabulators.

Additionally, the secretary of state’s office requires counties to provide ballots printed by its ballot-on-demand system for the logic and accuracy test the state performs in every county before each election.

In California, the certification process means counties put ballot-on-demand systems through a rigorous testing and procurement process before selecting one.

In Orange County, Kelley said he spent 18 months writing the request for proposals for the county’s election system, including the ballot-on-demand system, and it took three years for the county to decide and purchase the new system, which used the B432s.

He considered the reliability of the printer, the speed the printer could print on both sides, the cost of the toner, and other factors, he said. When he accepted equipment, he ran a high volume test on each printer.

In Santa Clara County, the bid the county put out for printers specifically required the printer manufacturer to prove ballots had the capacity to handle the demands of the county’s elections, according to the bid specifications the county gave Votebeat. That included being able to print high quality on both sides of the ballot using up to 100-pound paper.

In retrospect, it may seem important for the county to have run high-volume tests on all printers, Lindeman said, but “that feels like gilding the lily.”

Purcell, the former county recorder, said while it’s difficult to anticipate every scenario that could occur on Election Day, election officials should be able to address the problem for the future.

“We have always found there is a solution to everything,” she said.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.