A state-owned eight-seater airplane touched down in Yuma County on the last day of June to deliver a team from the Arizona secretary of state’s office to a nondescript building on Main Street for a crucial test — one they hoped could help rebuild public confidence in elections.

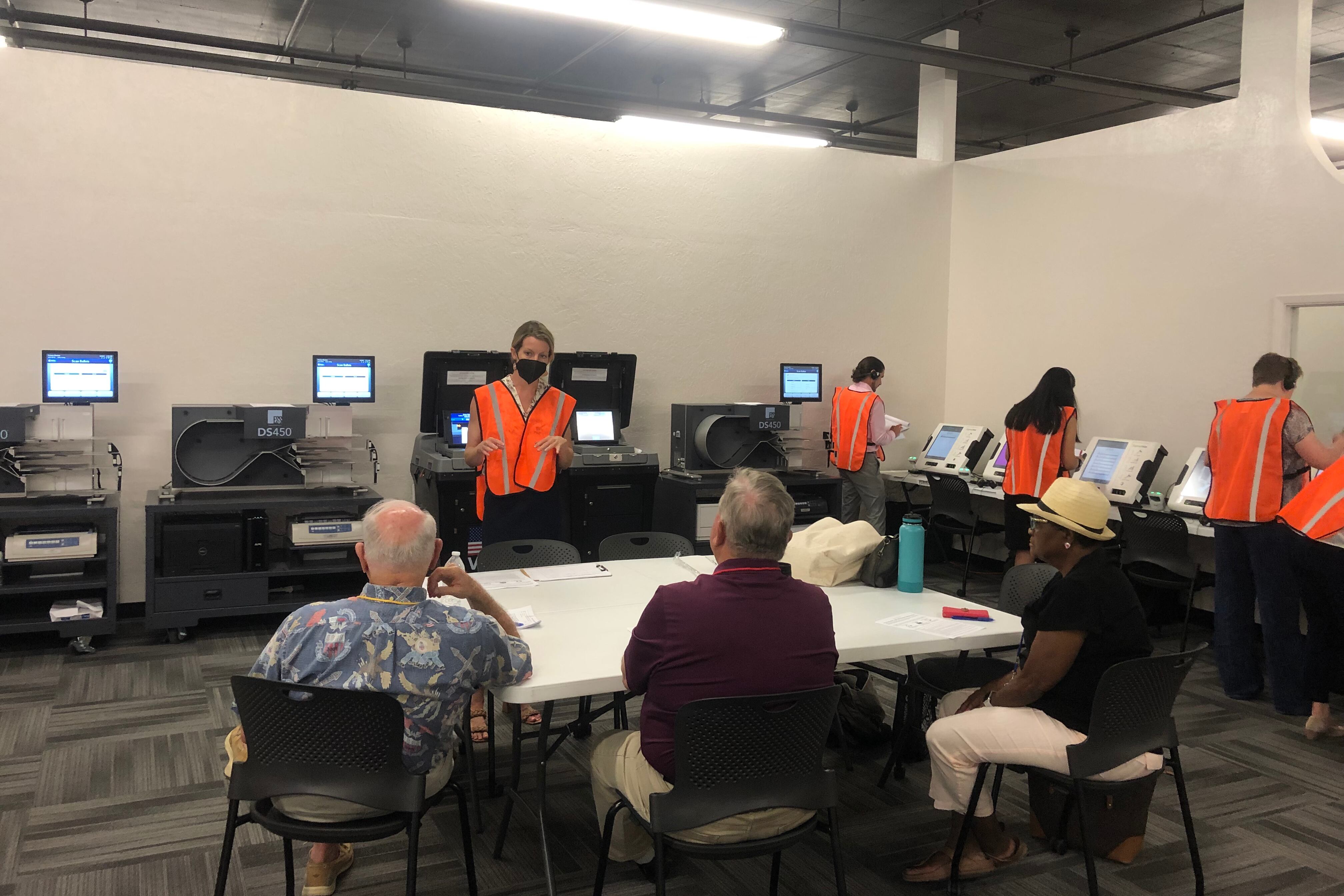

The secretary’s staff wore orange vests to distinguish them from others in the room. Legally required observers for the local Democrats, Republicans, and Libertarians wore lanyards in colors associated with their parties. A table stacked with waters and sweet treats sat near the stars of the show: the county’s voting machines and tabulators.

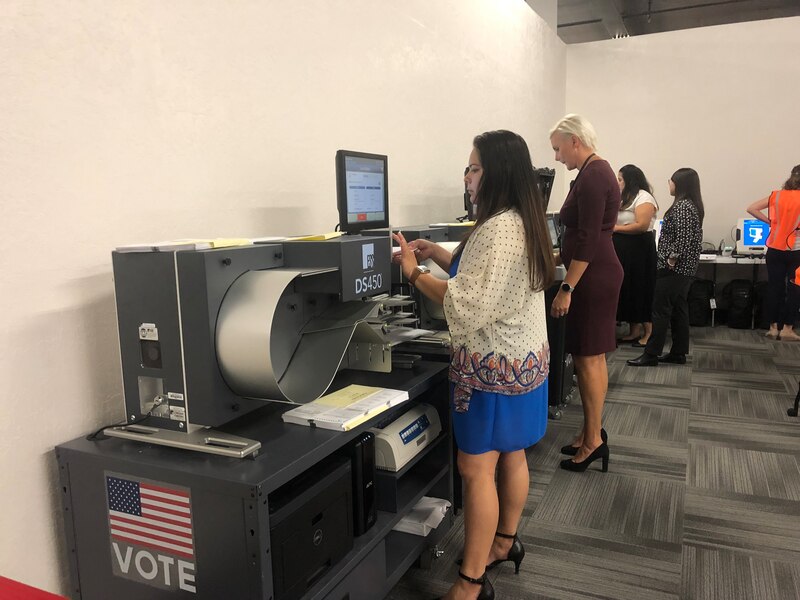

The logic and accuracy tests, required by state law, must be successfully completed before any Arizona voter can cast their ballot and before counties can count any votes. They serve to confirm that all voting machines work properly and meet every state requirement, no matter how arcane. They test whether each counting machine accurately tallies a predetermined, marked set of ballots.

The tests are relatively obscure. But election machines featured prominently in all kinds of conspiracy theories after the 2020 election. These tests are public officials’ chance to combat that, but in order to convince a skeptical public, election officials must first get the skeptical public to show up. Despite widespread wariness and unfounded accusations that voting machines could be used to cheat, few people come to watch the lengthy, intensive tests that the machines undergo.

Aside from the required party observers and county and state staff, only two members of the public — one a reporter and one a lawyer for the Democratic Party — were in the audience for the early morning test in Yuma.

If members of the public had come to observe, they would have seen just how thorough these tests are, and the minute details they’re checking.

Like the color of text displayed on a ballot machine, a small snag in Yuma’s test.

The screen on an accessible voting machine displayed the candidates’ political parties in black text. Per the state’s Elections Procedures Manual, the text color should have corresponded to the printed ballots — red for Republicans, blue for Democrats, and yellow for Libertarians.

The state testers, on their tiny airplane, would need to come back to Yuma.

How logic and accuracy tests work

The idea behind a logic and accuracy test is simple: to ensure the ballot tabulation machine’s results match the vote totals from the pre-marked ballots. We know we marked two plus two, which equals four, for instance, so the machine count should arrive at four if it’s working correctly.

“It’s really the starting point of making sure that the election has been set up correctly and that it’s correctly capturing the will of the people in how they cast their vote,” said Tammy Patrick, a former federal compliance officer for the Maricopa County Elections Department who is now a senior adviser to the elections program at the nonprofit and nonpartisan Democracy Fund.

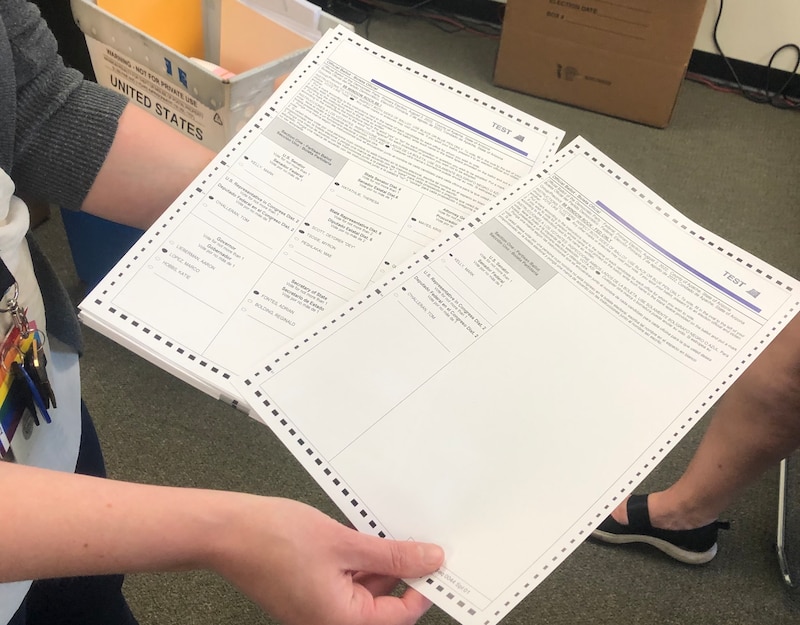

For state and federal races, the secretary of state’s office compiles a packet of test ballots marked with real candidates, though counties aren’t told in advance which ballot choices are marked. The office will then run those ballots through machines, which must line up with the totals predetermined to be correct. If they don’t, the county has to be retested. Once the test is complete, they zero out the machines again.

Arizona’s tests don’t stop there. Any accessible voting machine or print-on-demand ballots have to be tested before they’re used by voters, too. And the secretary of state’s office checks all elements of the process — even those that wouldn’t directly interfere with voting — to make sure they comply with state law.

Some counties have tried to bring more people in, issuing press releases or inviting skeptical locals. Others livestream the event, recognizing that many don’t have the option to watch an election test in person because of work or family commitments. And in Mohave County, in particular, an enthusiastic longtime elections director finally got a decent crowd this year.

Yuma County test gets redone

In Yuma, before the testing began, observers had to verify the machines were set to zero, making sure no previously recorded votes were lingering in their memory banks. Then, staffers began marking predetermined choices on accessible voting machines, touch-screen devices which are required by law to provide voters with disabilities a way to cast a ballot. The staffers listened on headphones to test whether required audio versions available for blind voters — in multiple languages, including English, Spanish, and Indigenous languages in some places — were accurate. Hundreds of ballots flew through tabulation machines, which tallied up votes for each candidate.

For the partisan observers, the tests are meant to help instill confidence in their local voting procedures and give them eyes inside the process. They can go back and assure their party faithful that everything they saw was above board, or, had anything serious gone wrong, alert them.

Russell Jones, the chairman of the Yuma County Republican Party, served as his party’s observer this year. He typically calls on precinct committee members to fill the role so more people can learn how the machines are tested, but he couldn’t get a volunteer for this year’s primary tests.

“It’s just a way to reassure, as leadership in our parties, to our boots on the ground folks that the system’s integrity is there,” he said.

Throughout the test, staff explained all steps of the process to observers and the public, including the moment when it was clear there was a problem: the text-color issue. The problem wouldn’t have deprived a voter of their right to vote or affected the county, but it was the law nonetheless, and a testament to how fastidious the elections officials who carry out these tests can be.

Yuma officials got to work reprogramming the machine to show the colored text while the secretary of state’s team moved on to run tests in another county.

Later in the afternoon, the crew flew back to Yuma to retest the machine. The county passed easily, as did all 15 Arizona counties before early voting started on July 6, after a whirlwind week dotting across the state.

It’s rare for the county to need a retest, said Tiffany Anderson, the Yuma County elections director. She chalked that up to the increased scrutiny on all elections officials, though she was frustrated that the minor error held up the test.

For Jones, the test shored up his confidence in that part of the process, though he and others in the local GOP still have concerns over other things, like external ballot drop boxes.

“It’s a good system, so it’s important that I be able to relate to all of my folks, it’s working, there’s not going to be fraud at this level,” he said. “Once it’s here, in this process, I’m certain it’s going to be handled.”

What happens behind the scenes

Before the logic and accuracy tests begin, Christine Dyster, the deputy elections director at the Arizona secretary of state’s office, dispatched a team of interns to a bland room at the state Capitol to compile ballots using a meticulous system of checklists and color-coded labels to track who completed each step of filling out test ballots.

She receives ballots directly from the printers, not from the counties, so the counties don’t know which precincts the tests will be assessing. There are scripts that show how each ballot in a set should be marked to arrive at the predetermined total counts, which let the team members know which bubbles to fill.

Her team triple-checks their work to get multiple sets of eyes on a ballot and ensure that counts match up with the intended predetermined totals. This year, the interns came up with the idea to pronounce names slightly differently each time they were proofing (sometimes using initials or last name, then first name) so they didn’t get lulled into a monotony that hindered their accuracy.

“We’re human. We check and we check and we check again. If it doesn’t match, we do a different style of counting to make sure that it wasn’t just a calling-out error or tallying error,” Dyster said.

The tight timeline is in part because of law, in part because of practicality, Dyster said. The counties work quickly, after the periods designated for candidate filing and challenges end, to compile the many ballot types they need before proofing them and sending them to a printer. They also must configure and program accessible machines with all legally required elements and audio. And they can’t start using those machines, or their tabulation equipment, until the state conducts logic and accuracy tests for state and federal races.

The counties work diligently to prepare for the tests, making sure all their many ballot types are ready to go, their accessible voting machines meet all legal requirements, and their tabulation machines function correctly.

For the big day, they often put out treats and drinks for the staff and observers, a small thank you to the people involved in a critical election process.

This year, several counties had relatively minor problems with their logic and accuracy tests during the first pass: language mispronunciations or inaccuracies on the accessible machines’ audio-assistance recordings were the most common error, particularly for Indigenous languages.

“When it comes to the accessibility of voting, nothing truly is minor, but [what we found was] nothing that would prevent somebody from accurately casting a ballot,” Dyster said.

(Coconino County passed its tests for all but one tabulation machine, which was running too slowly to complete the test. Coconino has one tabulator that passed the L&A, and the slow one won’t be used until it passes during a revisit, Dyster said.)

The tests draw scarce audiences

Despite the high level of scrutiny on elections since 2020, including in counties such as Yuma where conspiracies have taken hold, the public does not routinely show up to logic and accuracy tests.

Yuma County, for instance, put out a required public notice in the English and Spanish newspapers of general circulation (Yuma Sun and Bajo el Sol) for its test and also sent a press release, a new step this year, Anderson said. The department does more public outreach now and will go to almost any community group that invites them to talk about elections, hoping that if that group learns more, they can share accurate information and debunk inaccuracies within their circles, she said.

“That takes a lot of energy, though, … so it’s difficult when we don’t have a broad reach to larger swaths of our community,” Anderson said.

Some counties, including Maricopa, the state’s largest and most frequently scrutinized, livestream the logic and accuracy testing.

In previous years, most counties didn’t have outside observers, aside from those required by law, Dyster, of the secretary of state’s office, said. This year, all but one county had at least one outside person watching. Some were really bought into the process, she said, like a Republican observer in Pima County who was giving a tour of the tabulation facility to others when the secretary of state’s staff arrived. And there was one man who attended the Navajo County test who asked a lot of questions but was skeptical of the answers, though that was a rarity.

“Whether or not he believed our answers or cared to hear our answers, that was up to him, but we certainly could answer every single one of them. It’s the world we’re living in right now,” Dyster said. “I was pleasantly surprised how few people like that we encountered.”

In Mohave County, a heavily Republican county in the northwest corner of the state, longtime elections director Allen Tempert saw a massive increase in attendees this year — a crowd of about 20 people. Some were local Democrats and Republicans (more GOP in this red county), while others were new staff who Tempert thought should see the results of their work. A couple were members of the public who had come to him asking questions days before the test, prompting him to suggest they could get their questions answered there.

This year, Tempert said people attending the test mentioned that their parties directed them to show up and observe.

It’s his “goal in life” to bring people in, show them how his job and their democracy works, answer their questions, and see them leave with understanding and confidence in elections, he said.

During the test, the attendees peppered Tempert and his staff with questions, which he was happy to answer — and glad they came ready to ask.

“I felt like I was a game show host sometimes, just like, OK, anybody else out there? How about you in the blue hat?” he joked. “I don’t really recall most of the questions, but they were all questions I had answers right away to, they were all very procedural.”

Dyster said the Mohave crowd at first made her a “little nervous,” given the small attendance typically seen at logic and accuracy tests. There was skepticism and tough questions at the beginning, but the state’s team got a standing ovation at the end, which she credited largely to the work the elections department in Mohave County has done with the public.

“At the end, I feel like we walked away with a lot of people more confident in the process than when they started the day,” Dyster said.