Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

Young adults living on or near college campuses in Arizona are disproportionately affected, and potentially disenfranchised, by the state’s unique voting laws requiring documented proof of U.S. citizenship to vote in state and local elections, a Votebeat analysis found.

The laws have since 2013 been splitting the state’s voters into two buckets: Those who have provided documented proof of citizenship, and those who haven’t. Those who haven’t are placed on a “federal-only” list, and are only permitted to vote in federal elections.

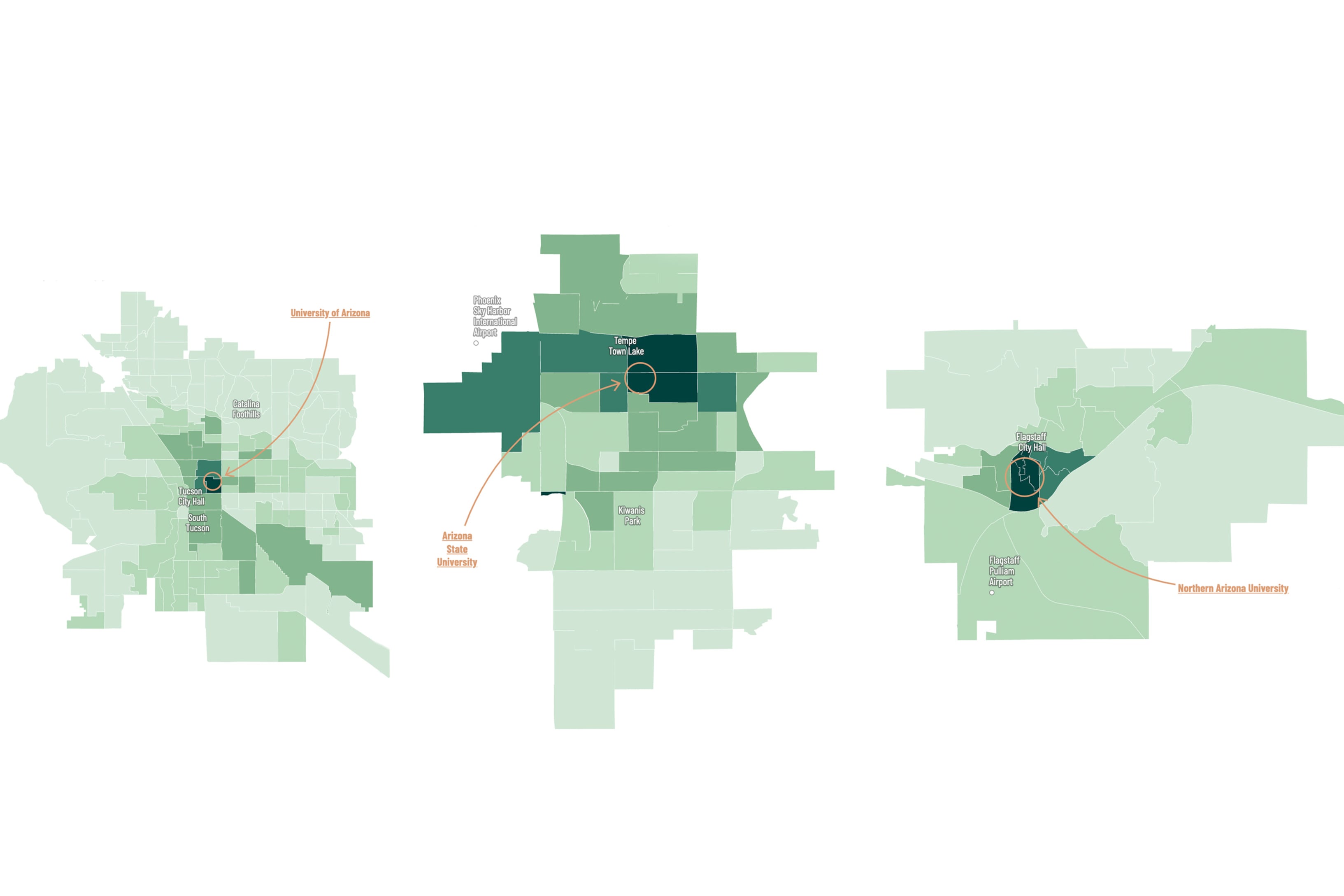

In pushing for stricter laws, Republican lawmakers have said the federal-only list potentially allows non-citizens to vote illegally. But an analysis of the roughly 32,000 voters on the federal-only list, and where they live, found that federal-only voters in the state are concentrated in areas where residents are simply unlikely to have easy access to documents proving their citizenship, such as college campuses and a Phoenix homeless shelter.

In fact, 18- to 24-year-olds are three times more likely to be federal-only voters than people over the age of 24, according to an analysis comparing the ages of federal-only voters with U.S. Census estimates of the entire state population.

Student voting advocates say that the findings make a known problem even more clear: The requirement to provide documents to become a full-ballot voter is often preventing students who move to Arizona to attend college from voting in local and state elections.

A federal judge is weighing two new provisions that would make these laws even more restrictive, and require more frequent citizenship checks, leaving voting advocates worrying that even more eligible voters will be blocked or discouraged from voting. The final day of the trial is Tuesday, and the judge will soon decide if those two provisions will go into effect.

“They are just trying to make it harder for people to become voters,” said Kyle Nitschke, a co-executive director for the Arizona Students’ Association.

There are only two voting precincts in the state with more than 1,000 federal-only voters. One is in Tucson, encompassing most of the University of Arizona campus and its dorms, along with student housing south of campus. The other is the Tempe precinct that encompasses the vast majority of the Arizona State University campus, including the Memorial Union where some voter registration drives and civic engagement events are held.

When conducting voter registration drives on these campuses, Nitschke said, the students’ association often speaks with out-of-state students who don’t have Arizona IDs, and haven’t brought their birth certificate or passport with them to school.

After seeing Votebeat’s analysis, One Arizona, an organization that provides resources to a coalition of 30 community groups and helps organize voter registration drives, said they were going to research the topic further, for future training purposes.

“There does seem to be significance in the correlation to campus ties and we’re interested in investigating further,” Paloma Ibañez, One Arizona’s interim executive director said.

Who is on the federal-only list?

Arizona appears to be the only state that is currently enforcing a law requiring documented proof of citizenship to vote. Hence, it’s the only state with a “federal-only” list.

After Arizona enacted its proof of citizenship law in 2004, it began rejecting all voter registration applicants that didn’t include documented proof of citizenship.

Then, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that, under the Voting Rights Act — which doesn’t require documentation — Arizona had to let these voters vote in federal elections. The state created a system in which it rejected any state voter registration application that didn’t have documents proving citizenship, but if the voter used a federal form, they would be registered as a federal-only voter. Because few voters use the federal form, the federal-only list was relatively small at the time.

After groups sued, in 2018, the state agreed to start adding voters to the federal-only list regardless of whether they used the state or federal form. That caused the list to grow, and fast.

As of October 2019, there were about 17,000 federal-only voters, according to state data. By October 2020, there were about 36,000.

Federal law requires voters to attest that they are a citizen by marking a checkbox on their voter registration form. To be sure, it’s still possible that some of the voters on the federal-only list may not be U.S. citizens.

In recent reports to the state Legislature, the Secretary of State’s Office wrote that, in the first six months of 2023 alone, 1,324 registered voters self-reported that they were not U.S. citizens when summoned for jury duty. Counties that receive information from these jury reports cancel these voters’ registrations after sending them a notice allowing them 35 days to provide documents proving citizenship.

But it’s rare that non-citizens are caught voting illegally. Since 2010, the Attorney General’s Office has not prosecuted or convicted any non-citizen for illegal voting. There are two pending prosecutions for non-citizens who have either registered or voted in Arizona, according to a spokesperson for the Attorney General’s Office, but the details of those cases aren’t public.

Aimee Yentes, vice president of the conservative Arizona Free Enterprise Club, said the voter citizenship laws, new and old, are aimed at providing consistent rules upon the agreed-upon principle that only U.S. citizens should vote.

“If you don’t require documented proof of citizenship, it’s an invitation for polluting your systems with votes that shouldn’t be counted,” Yentes said.

The voting rights groups that sued the state for the new laws claim that they would disproportionately disenfranchise minority voters. Arizona doesn’t collect race or ethnicity information from voters when they register, so Votebeat’s analysis wasn’t able to examine that claim.

But in trial testimony, Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida, told the judge that his analysis found that federal-only voters live in communities that are more diverse, compared to full-ballot voters. The average community for a registered voter in Arizona is 62.9 percent non-Hispanic white, he said, but the average community of a federal-only voter is 47.3 percent non-Hispanic white.

Also, naturalized citizens may be more likely to be targeted for investigation under the new laws, and McDonald’s analysis found that naturalized citizens are more diverse than the overall voting population in Arizona.

For the most part, federal-only voters are spread evenly across the state, with small numbers appearing throughout thousands of precincts, based on a Votebeat analysis of October county registration reports and a federal-only voter list provided by the state in mid-November. Most precincts that have at least one federal-only voter have fewer than a few dozen total. But of the dozen outliers with more than 300 federal-only voters, all but one are located at least partly on a college campus, the data show.

That exception can be explained, in part: It contains downtown Phoenix’s homeless shelter, an address Arizona residents without permanent housing — and therefore without a permanent place to store important documents — can use to register to vote. There are 82 federal-only registered voters at the Central Arizona Shelter Services campus, according to Maricopa County data, but only 12 of them are active voters.

Leah Miriam Mundell, an associate professor at Northern Arizona University, until recently ran the NAU Votes Coalition, an on-campus voter advocacy group that does voter outreach and registration. Mundell said it’s always a challenge for out-of-state students to become full ballot voters because of the documentation requirement.

Only about 19,000 of the about 32,000 voters on the list now are active voters. The rest are “inactive,” meaning they can’t vote until they prove they’re eligible, often because the county has a question about where they live. Counties cancel voter registrations for inactive voters if the voter doesn’t respond to notices regarding their eligibility, or they don’t vote, for two federal election cycles after they’re placed on the inactive list.

Most of the federal-only voters, or 52.6%, aren’t affiliated with a political party; 28.8% are Democrats; and 14.6% are Republicans. They’re disproportionately young: 36.2% of them are ages 18 to 24, when 9.8% of Arizonans are that age, according to American Community Survey estimates.

The high number of federal-only voters on college campuses doesn’t surprise Nitschke. The organization ran voter registration drives at four of the state’s college campuses in the fall at ASU, UA, NAU, and Grand Canyon University in Phoenix. During the drives, students fill out and turn in the registration form on the spot. They often don’t have an in-state driver’s license, having just moved here to attend college, Nitschke said.

About 35% of the students the organization helped register using paper forms during the drives this fall left the Arizona driver’s license or state ID field blank, and so were presumably registered as federal-only voters, Nitschke said. Of those 192 students, the vast majority provided the last four numbers of their social security number. (Social security numbers don’t count as documented proof of citizenship under the state law.)

The association gives the students instructions on how to later provide the documentation needed to become a full ballot voter, such as by emailing the county recorder’s office, Nitschke said, but he assumes many do not follow through.

The court case considering Arizona’s original proof of citizenship law found that it wasn’t an undue burden to require voters to provide documents proving their citizenship in order to vote.

The new laws passed in 2022, HB2492 and HB2243, would subject federal-only voters to regular citizenship checks and potential investigations by the attorney general. Voting rights advocates told U.S. District Court Judge Susan Bolton that the laws would require officials to regularly use faulty or old databases to check citizenship that would likely incorrectly flag non-citizens and would not provide sufficient notice to those voters, potentially resulting in the disenfranchisement of eligible voters and an uneven system around the state.

The laws were stayed and have not gone into effect because of the pending court case. Bolton issued a preliminary ruling in September that decided some of the most significant portions of the laws won’t stand. That includes rules that would have blocked Arizona voters who don’t provide documented proof of citizenship from voting for president or by mail. But that decision could still be appealed.

Mundell said the current system is already too restrictive, and the new laws will inhibit student voting participation further.

“Any way we are restricting college students from participating is not beneficial,” she said.

In trial testimony, Nitschke told the judge that if the laws were in place, the organization would change its practice to turn students away who do not have in-state IDs or other documentation.

“I think we would see less students getting registered to vote in the state and see more students registering out of state or staying [registered] at addresses where they are not currently living — at their parents’ address,” Nitschke testified.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org. Kae Petrin is a data & graphics reporter for Votebeat. Contact Kae at kpetrin@chalkbeat.org.