Behind closed doors this month, in a caucus room that typically holds members from just one party, in a state defined by its political divisiveness, a rare bipartisan parley unfolded.

State Sen. Ken Bennett paced around the room explaining his idea for a Do-It-Yourself election audit. He wanted to create a path making it possible — though technically difficult — to confirm the validity of election results by precinct, race, or ballot, from the comfort of home.

“I just wanted to give people the opportunity to say, do you have trouble with any of that, the underlying concept?” Bennett said. Sitting before him were prominent figures from both political parties, including Democratic Secretary of State Adrian Fontes and Republican state Sen. Wendy Rogers. No one spoke up to object.

In a legislative session marked with hostility and party-line votes, this idea from Bennett, a Republican and a former secretary of state, has brought about a rare cross-party dialogue. Both sides set aside their talking points during the meeting, with no emphasis from Republicans on unproven theories of stolen elections, according to video snippets shared with Votebeat, and no stonewalling from Democrats.

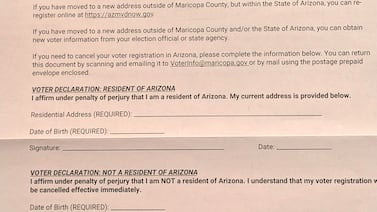

Bennett’s bill, SB1324, would make public a digital image of each ballot that is produced when the ballot is tabulated (which must be anonymous under law), the record of how machines counted the votes on each ballot, and a list of all registered voters. Analyzing all of this together, it would theoretically be possible to verify that the machines counted the votes accurately and that the people who voted were eligible voters.

An example Bennett gave at a separate committee meeting last month: If Abe Hamadeh, a Republican who lost his campaign for attorney general by just 280 votes last November, doesn’t believe thousands of voters would leave his contest blank, “well, just look at the ballots and see.”

“This is the kind of transparency, tractability, and public verifiability I think people are looking for in our elections,” Bennett said.

But Democrats, county election officials, and voter advocacy groups, made wary by an endless stream of conspiracy theories, worry this will give such theorists more information to work with and ammunition for more believable lies. They also worry that under certain circumstances, someone could tie a particular ballot to a particular voter.

“Allowing conspiracy theorists to conduct home-based audits will not encourage more trust,” state Sen. Juan Mendez, a Democrat, said at a committee hearing last month. “This will only add more kindling to the fire.”

While Bennett believes the proposal may reduce the number of election challenges by allowing candidates to see for themselves where they lost, others, such as Alex Gulotta, Arizona state director of All Voting Is Local, aren’t buying it. Gulotta said it would open up endless information for internet sleuths and self-proclaimed election experts to manipulate evidence with a goal of convincing county supervisors not to certify their elections. Last year, for instance, election fraud activists obtained ballot envelopes and inaccurately claimed voter signatures were invalid without having all relevant information.

“This gives them much more ammunition to do that in the very dangerous period after people finish voting and before the state certifies the results,” Gulotta said.

The bill appears to acknowledge the information might be used to provide purported evidence for lawsuits, as well. The legislation would change the law to allow more time for election contests to be filed, from five days after the state finalizes election results to seven.

Bennett says he is willing to compromise. He is willing to amend the bill, he says, to withhold ballot images in small precincts — how small is still under discussion — in an attempt to stop people from identifying the choices of an individual voter by tying them to a ballot. And while the initial idea was to post all the ballots and data online in a downloadable format, Bennett says he is willing to change it so that the images are made available only by request, perhaps with a cost associated.

Democrats elsewhere have championed the idea of making ballot images public. Colorado and Maryland are among the states where the law already makes ballot images public records, and the main group pushing for them to become public here and across the country, Audit USA, is run by Democrat John Brakey.

The question is whether Bennett and Brakey can convince Democrats such as Mendez to vote alongside Republicans such as Rogers on a Republican idea aimed at improving trust in elections. That gets especially challenging because those Democrats blame Republicans like Rogers for creating the mistrust in the first place by spreading unfounded theories of widespread fraud. Without broad support, Bennett and Brakey realize that, to Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs, their diligently crafted proposal will look like all of the other partisan bills on her desk – bills she has vowed to never sign. Hobbs has told Votebeat that she is open to approving election bills if she believes they will benefit voters.

Hobbs’ office did not respond to a request for comment on this bill.

How the DIY audit system would work

In the caucus room, Bennett spoke of the four fundamental steps in the bill.

First, he said, shortly before the election, counties would make available the full list of registered voters but with only some personally identifying information, such as addresses and year of birth. In an example he has given repeatedly, Bennett says that would allow people to see that there is only one Ken and one Jeanne Bennett living on his particular street in the Watson precinct in Prescott.

Second, shortly after the election, counties would make available a list of everyone who voted in the election, with the same identifying details. That would allow people to do a so-called “soft match” to verify that each ballot came from a registered voter.

Third, the counties would also make public a digital copy of each ballot. And fourth, the counties would make public what’s referred to as a cast vote record, an enormous dataset frequently referred to as a “CVR” that serves as the official record of how tabulation machines counted votes. It often comes in the form of a giant spreadsheet, with each row representing an anonymous ballot and the votes selected on it.

Many different analyses could be done with those records. At the most basic level, if a voter noted their ballot’s ID number, they could later look up the scanned copy and see how the machine counted their votes. More sophisticated analysis of cast vote records in the past has identified the precincts where Republicans were most likely to vote for Joe Biden in 2020, or were most likely to leave the contest blank.

Some counties in Colorado, where ballot images are public records but not required to be posted online, have made it easy for their voters to analyze voter selections on ballot images. The counties pay ($3,300 per election according to two contracts Votebeat reviewed) for an add-on service from Dominion Voting Systems to place their ballot images on a website allowing voters to easily sort the images and contests they want to study.

But this type of system costs time and money, and it’s not guaranteed many people will use it. El Paso County, Colorado, learned that firsthand. Over the course of four elections, only about 135 people have created usernames to access the site with ballot images, in a county of about 466,000 registered voters. Karl Nordstrom, the county’s information systems manager, believes that about one-third of that number is internal staff or other counties’ election administrators.

“The general desire to look into the election, post-election, is very low, even in El Paso, a county that has historically shown to have a lot of people who are election deniers. The public at large really doesn’t show up,” Nordstrom said.

Gulotta and other voting advocacy groups are extremely worried about the timing outlined in the current bill, which would require counties to release the ballot images and cast vote record within 48 hours after they finalize results — which in most cases would be days before the state certifies the election.

Given that county supervisors in Arizona and elsewhere already are using flawed evidence to try to justify delaying election results, Gulotta said this will exacerbate the problem.

Bennett knows firsthand what kind of misinformation can spread when inexperienced auditors are given election data they don’t understand. He served as the Senate’s liaison to the Cyber Ninjas as the company and its contractors attempted to hand count 2.1 million ballots without even initially asking for the cast vote record. The Cyber Ninjas falsely claimed that thousands of Maricopa County voters had moved out of the state or county, but an investigation by the attorney general’s office later found Cyber Ninjas had identified these voters using inaccurate commercial databases and the voters were still registered.

But the idea for this at-home audit came partly from that experience, he told lawmakers, which he said prompted him to believe there needed to be some way to make elections more transparent. Brakey worked with Bennett during the audit, and has been pressing the idea of public ballot images here since unsuccessfully suing Pima County for the images in 2016.

Brakey wants bipartisan support for the bill so that if it passes, he can tout that to support expanding the idea across the country.

“We want to send the message that we will never do a [Cyber Ninjas-style] audit again because we figured out how to do elections that are transparent, trackable, and publicly verifiable,” he said.

Bennett and Brakey are counting on Fontes to help them get the support they need. Fontes is supportive of the idea, and has been willing to explain to lawmakers how the state and counties would make it work.

Last year, he stood up for the idea even though his then-opponent for secretary of state, former state Rep. Mark Finchem, had introduced the bill at the time.

“Just because a Republican proposed this legislation, a lot of Democrats opposed it, and I thought, that’s kind of crazy because it’s a good idea,” Fontes said in a video he posted on Facebook in April 2022. “Even a broken clock can be correct every once in a while.”

Maintaining the secret ballot

Behind Bennett in the caucus room were three whiteboards, with the middle one containing one of the Democrats’ biggest concerns, written in red and underlined twice: voter anonymity.

Fontes sat across from Rogers, and on either side of him were Rep. Alexander Kolodin, an attorney who makes a career of helping Republicans challenge elections in court, and Republican House Speaker Ben Toma, who has not spread election conspiracy theories. Toma is sponsoring the House version of the bill.

Bennett told the group that his bill indemnifies counties from being held liable for releasing ballots where a voter has somehow written something to reveal their identity.

Voters sometimes sign their ballots, perhaps thinking that it’s required, or write their name in the write-in box. Bennett said preventing this will mean educating voters so they know that an image of their ballot choices will be released publicly.

“I’ll have to talk to my mom,” he joked. “She writes my name for president.”

Worried about ballot secrecy, El Paso County, Colorado, goes through a laborious process each election to redact all personally identifying information that voters write on ballots before the county releases the ballot images. This takes a full week after the election for a primary and longer for a general election, and costs at least $3,500 to pay temporary staff, according to election officials there.

Nordstrom said it’s a stressful process, but it’s worth it to keep ballots private. As the county weighs whether to continue to put the ballot images online, he said they are weighing the burden and cost of it with the customer service it provides.

Arizona counties may not be able to redact personal information that voters write on their ballots, even if they wanted to, because Bennett said his bill will call for unaltered ballot images.

“We don’t want to give anyone the idea that these ballots have been doctored,” he told lawmakers in the bipartisan meeting on March 2.

Gulotta said this issue is a dealbreaker for his group — voter markings must be removed to protect the secrecy of the ballot, he said.

The other concern regarding ballot secrecy, in which an analyst may be able to tie a ballot to an individual, is hard to solve, said Benny White, a Republican elections analyst in Tucson. White is known for his work after the 2020 election using the cast vote record to show how former President Donald Trump lost the election in Arizona.

Even if Bennett was to not release the ballot images from small precincts, there are still so many subgroups of voters within precincts that White said it still might be a problem. For example, he said, one precinct might have just one person who cast a provisional ballot.

While Maricopa County is supportive of the bill, Jen Marson of the Arizona Association of Counties, which represents election officials across the state, told Votebeat her group is still opposed to it, despite Bennett’s attempts to negotiate. At a committee meeting last month, she told lawmakers that the counties had concerns about voter privacy, how they would handle differently-processed ballots such as Braille ballots, and how the counties could track down someone who used the information in a malicious way.

Advocates for the bill say all those problems are solvable.

State Sen. Priya Sundareshan is one who is not convinced this is a good idea. The Democrat has publicly praised Bennett for his efforts to gain support, saying she has great admiration for him. But she’s too concerned to vote for his proposal.

In the meeting in the caucus room last week, she told Bennett that she and other Democrats may draw a hard line for what they will approve: They only want the cast vote record released, and only after the election has been certified.

Democrats won’t go along with “anything that could lead to multiple challenges, things that delay the certification process,” she told him before leaving the meeting. “That’s what we want to avoid.”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.