Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

Paper rolls the size of giant tires, together weighing 10 tons, are stacked up high inside a ballot printing warehouse in an industrial area of Phoenix.

Meanwhile, in a paper mill somewhere in Canada, there’s a 350-pound, 6-foot-long machine that imprinted secret watermarks on that paper.

If you can pick them up (you’ll need a crane), they could soon be yours!

You may be asking how we got here. Like so much in Arizona elections, it’s a long story that starts with a conspiracy theory and ends in the southeast corner of the state.

Cochise County, which garnered national attention for its attempts to upend the state’s midterm election, has found itself in a bit of a jam — a paper jam, if I may — after a state pilot project ended prematurely.

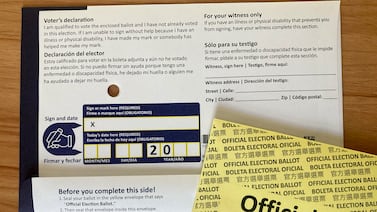

County Recorder David Stevens, who helps run elections, agreed in fall 2022 to participate in a Republican-initiated state grant program designed to test out security features such as watermarks and invisible fibers on ballots. But he didn’t anticipate how long it would take to get up and running.

Stevens missed the grant’s deadline and tried to get an extension. County officials decided instead to scrap the whole thing. But Stevens had already paid Runbeck Election Services $187,500 to order the massive rolls of ballot paper and commission the giant watermarking machine.

What to do with it? The state grant is over and there’s no county interest in spending local dollars to cut the paper into ballots or transport it, which would have costs thousands. Runbeck is reimbursing the state the $12,000 it would have cost just to cut the ballots. So the next option on the table is a potential public auction that would let state taxpayers recoup some of their outlay.

Of course, there are always just a few small wrinkles to work out. In this case, it isn’t completely clear who actually owns the watermarking machine, called a dandy roll. Or who would buy 10 tons of ballot paper that might not even be usable for ballots — it hasn’t been tested yet. And, of course, there’s the question of whether selling the ballot paper could actually create the kind of election security risk the pilot was meant to prevent.

Each roll of paper could make about 20,000 ballots.

Runbeck CEO Jeff Ellington has been graciously giving me regular updates as the project got started, and then got shut down, and then fell into limbo.

Last I heard: The huge rolls of paper are still on his warehouse floor.

But I still have some questions about how we got here, and how all of it will play out.

Bamboo fibers and watermarks

It all started shortly after the 2020 election, when a false claim asserting that someone had flown fake ballots from South Korea to Maricopa County to rig the county’s election for President Joe Biden began circulating.

A few months later, state Rep. Mark Finchem was in the basement of the Legislature with a blacklight and a sample ballot provided by Stevens. He knew of a company called Authentix (a little more closely than he let on, a Votebeat investigation found) that said it could put watermarks and all sorts of other features, such as holograms, onto ballots, and he was holding a demonstration for his colleagues. Such special features, he said, would make ballots harder to counterfeit.

Soon, Cyber Ninjas came to town and started shining their own blacklights on the 2020 ballots, looking for bamboo fibers or watermarks. None turned up.

Nonetheless, Finchem tried to convince the Legislature that year and the next to enact a state law requiring the use of Authentix’s secure ballot technology, without specifically naming the company. What he got was a $1 million state grant that offered counties a chance to test out exactly what Authentix could provide, again without specifically naming the company.

Stevens was the first and only county recorder to apply to participate in the trial.

By January 2023, he was working with Runbeck to order the paper and get the dandy roll made, though there wasn’t a public process to request proposals. But there were a few other things going on with Cochise’s elections in that timeframe, and progress on the trial moved slowly.

By the time Stevens brought Authentix’s bid before county supervisors, the initial May deadline for the grant had passed. Members of the public spoke against the proposal, raising questions about the company’s ties to Finchem, and the supervisors voted not to move forward.

The trial fell off the radar, except for a local watchdog, who kept asking questions. Her questions prompted me to circle back, too, and find out what happened to that paper in the warehouse.

10 tons of paper

In an interview in his office in Bisbee last month, Stevens told me that when the supervisors voted against extending the timeline for the project, they cut off his authority and funding. The paper still needs to be cut into ballot-sized pages, a sample ballot must be printed on the paper, and then those must be tested in tabulators, but that would all cost the county money.

I asked Stevens why he needed so much paper for this trial in the first place.

He responded by asking me if I’d had a Big Mac recently. I said no, and wondered where this could be going now.

Stevens said it’s an analogy he uses to describe how product testing works. A Big Mac only has eight main ingredients (please note I didn’t fact check this), he said, but you can build those eight ingredients into thousands of hamburger combinations.

In other words, each feature on the ballot paper would need to be tested thousands of times, and in all possible combinations, through ballot tabulators and using different printers, to see which combinations the tabulators could accept and which they couldn’t.

Ellington later told me the same thing, without a fast food analogy. Oh, and one more thing: “The paper mill had a minimum.”

Either way, there’s still 10 tons of paper sitting in the warehouse.

After supervisors shut the grant down, the Arizona Department of Administration told Stevens that he could either keep the paper and dandy roll or sell them at a state auction, but the state would get the proceeds from any sale.

Straightforward, except it’s not clear who owns the dandy roll. The invoice between the county and Runbeck says that Runbeck will own the dandy roll after the grant work is complete. Stevens says he isn’t sure, and he contacted the state for clarification.

Ellington said he also contacted the state for clarification. He said even if someone else wanted the dandy roll, it’s “obnoxiously difficult” to move. It’s meant to stay in the paper mill, where it is used in the process of making the paper.

Because Runbeck believed it would keep the dandy roll, Runbeck made the design that the machine would imprint on the ballot a close replica of its own company logo, a checkmark, rather than something specific to Cochise County. That way, the company could later produce watermarked ballots for any county that wanted them.

I also asked ADOA for clarification on who owns the dandy roll. An agency spokesperson made it clear that it’s on the county to review its agreement with Runbeck and figure this out.

“We have consistently told them that is their responsibility,” said spokesperson Megan Rose.

Regarding the watermarked paper, it’s pretty clear it’s the county’s to keep, but neither Runbeck nor Cochise County seem to want it.

So, what’s the market for 10 unwieldy tons of it? State or county officials looking to move forward on a trial could buy it. Maybe a school could buy it, for endless art projects.

But auctioning it off might not be without pitfalls. Ellington raised the possibility of a buyer trying to introduce fake ballots into an election. Of course, there are numerous protections to make sure that doesn’t happen. Even if someone bought the paper and found a giant machine to cut the ballot papers with precision, they would still need to infiltrate a county’s secure election space, avoid cameras, employees, and political observers, and insert the ballots in such a way as to confound auditing measures in place to ensure only one ballot comes from each registered voter.

This concern, though, isn’t lost on Stevens.

“That is one of a couple concerns we ( the County ) are discussing,” he wrote. “The photo copying of a ballot can happen now, anyone just needs 80# paper, scanner, and printer.”

“This is,” he added, “what the grant was supposed to eliminate.”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.