Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

Republican lawmakers in Arizona privately pressured county leaders across the state to count ballots by hand instead of using machines, according to previously unreported text messages.

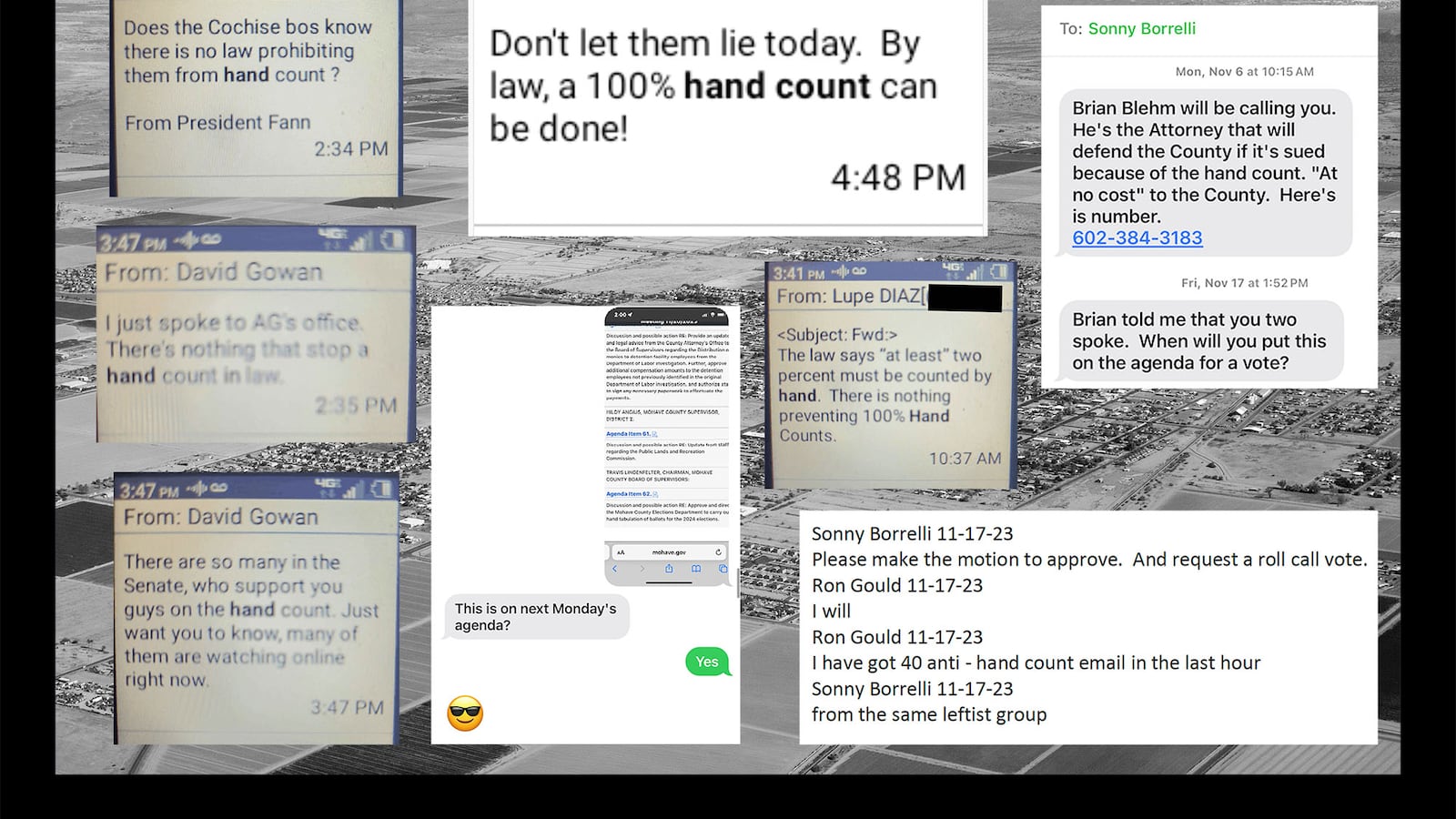

The messages, obtained by Votebeat through public record requests, are a window into how state lawmakers are trying to leverage relationships with Republican county supervisors — who decide how to count ballots in their counties — to promote a practice that state officials have repeatedly said would be illegal.

And it highlights how lawmakers have turned to counties to try to change how ballots are counted, after failing to change state laws.

In Mohave County, for example, messages show that Supervisor Travis Lingenfelter requested a vote on hand-counting ballots during the upcoming presidential election after state Sen. Sonny Borrelli, a fellow Republican who lives in the county, connected him with a lawyer who promised to represent the board free if necessary.

After Lingenfelter spoke to the lawyer, Borrelli checked back in. “When will you put this on the agenda for a vote,” Borrelli texted Lingenfelter. Lingenfelter replied with a screenshot of a meeting agenda for the next week, showing a scheduled vote.

In Pinal County, the day supervisors discussed hand-counting ballots in this year’s election, state Sen. Wendy Rogers, a Republican who represents parts of Pinal County, texted Supervisor Kevin Cavanaugh, also a Republican, to assert that hand-counting all ballots was legal — something the Secretary of State’s Office and state Attorney General’s Office have said is not true.

“Don’t let them lie today,” Rogers wrote.

Supervisors ultimately rejected their pleas. So far, all Arizona counties plan to use machines to count ballots for the upcoming election. The supervisors in Pinal and Mohave, specifically, decided against a hand count after the counties’ lawyers told them they would potentially be violating state law and could be held personally liable if they went ahead with it.

Adding heft to the warnings: Two Republican supervisors in Cochise County, Peggy Judd and Tom Crosby, are facing felony charges for allegedly conspiring to interfere with the county’s midterm election — in part by pushing for a full hand count of ballots.

Other newly obtained text messages from Cochise County, which American Oversight fought for in court and shared with Votebeat, show that a state senator was trying to pressure Judd during the public meeting when the supervisors held the key vote on hand-counting ballots.

State Sen. David Gowan, who lives in Cochise County, texted Judd just as the meeting began, appearing to pass along a message from another Republican, then-Senate President Karen Fann.

“Does the Cochise bos know there is no law prohibiting them from hand count? From President Fann,” he wrote, referring to the board of supervisors.

Votebeat attempted to contact every public official identified in this article, and included comments from those who responded.

Push for hand counts persists despite known drawbacks

The issue with hand-counting ballots is not just the law. Multiple studies, trials, and attempts to hand-count ballots across the country — including in Pinal and Mohave counties — have proven that hand-counting instead of using machines would cost more money, require hundreds to thousands more workers, lead to inaccurate results, and potentially delay or disrupt the certification of results. Yet the conversations about instituting hand counts continue in Arizona, especially as many of the county supervisors run for reelection this year.

Cavanaugh, who is running for sheriff in Pinal County, says he still thinks Pinal should expand its post-election hand-count audit, and he believes the board still might hand-count.

In Mohave County, Supervisor Ron Gould, who is vying to keep his seat on the board, sued Attorney General Kris Mayes, asking the court to rule on whether counties are required to use machines during the initial count of ballots. A hearing date hasn’t been set.

Many election lawyers have said state law is unclear on whether counties must use machines for the initial ballot count, but Secretary of State Adrian Fontes and Mayes, both Democrats, have said machines are legally required. In October, the Arizona Court of Appeals ruled that counties cannot legally hand count all ballots during their statutorily required post-election audit, but that ruling did not appear to directly address whether machines must be used during the initial vote count.

Gould has said he believes Mohave County’s current board would move forward with eliminating machines if a court deems it legal.

Senator texts Cochise supervisor: ‘Watching online right now’

The pressure campaign for hand counts has accelerated this year, but it began after former President Donald Trump began claiming falsely, and without evidence, that someone programmed machines to switch votes to President Joe Biden during the 2020 presidential race.

Multiple courts in Arizona and across the country dismissed the claims. Election officials have procedures and protections to verify machines are working properly.

Voters in most Arizona counties vote by hand-marking paper ballots that are then fed into scanners that tally the votes. The results of the machine count are verified by a manual audit of the paper ballots in a select number of races before the county’s results are finalized. If enough mistakes are found, by law, the county must continue to hand-count the votes on more ballots until the results are confirmed.

Just before the 2022 midterm election, a grassroots group led in part by Corporation Commissioner Jim O’Connor, a Republican, bombarded county supervisors’ email inboxes and filled the seats in county boardrooms with a call to stop using the counting machines.

Only Cochise County listened, and even there, the two Republicans on the three-member board — Judd and Crosby — wanted to keep using the machines for the initial count, but subsequently confirm those results with a full hand count.

On Oct. 12, the day after the supervisors discussed a hand count, Republican state Rep. Lupe Diaz texted Judd to assert that the law allowed supervisors to use the post-election audit to hand-count all ballots.

“There is nothing preventing 100% hand counts,” Diaz texted her.

Judd put the proposal on the agenda for an Oct. 24 special meeting of supervisors.

The meeting began at 2 p.m. At 2:34 p.m., Gowan texted Judd the message about Fann. A minute later, he texted her to say he had just spoken to the office of then-Attorney General Mark Brnovich, a Republican, and there’s “nothing that can stop a hand count in law.”

An hour later, as the meeting continued, Gowan texted Judd again. “There are so many in the Senate, who support you guys on the hand count,” he wrote. “Just want you to know, many of them are watching online right now.”

Judd, who used a flip phone at the time, said she didn’t immediately see the messages. “I had stopped reading any emails during that hectic time,” she said.

She also said it “wouldn’t have mattered anyway” and she was influenced by constituents.

She and Crosby voted that day to expand the county’s hand-count audit to look at more ballots than required by law. The motion they voted on was confusing, and many, including the Secretary of State’s Office, interpreted it as a vote for a full hand count.

In 2023, Mayes replaced Brnovich as attorney general and opened an investigation into that vote, as well as Judd and Crosby’s later efforts to delay the certification of the county’s election results. A grand jury concluded Crosby and Judd’s actions were a conspiracy and interference with an election, both felonies.

Crosby and Judd have pleaded not guilty. They are awaiting trial.

Texts show state lawmakers’ private requests to Mohave supervisors

Last summer, before the Cochise indictments, and as county election officials were starting their initial planning for the presidential election cycle, state Sens. Borrelli and Rogers toured the state to try to convince county supervisors to get rid of voting machines for this year’s election.

That included lobbying in Mohave County, where Borrelli lives and where he is now challenging Supervisor Buster Johnson for his seat in the July 30 Republican primary.

After Votebeat in January requested Mohave supervisors’ text messages related to hand-counting ballots, which the county is required to provide under state public records laws, the county attorney’s office said it asked supervisors to conduct a search of their own phones and provide any responsive records. The county attorney’s office did not independently conduct a search.

Initially, only Johnson provided records. After Votebeat pressed for more, Supervisor Hildy Angius also handed over messages. The law firm Ballard Spahr then sent letters on Votebeat’s behalf, demanding that the other supervisors respond to the request as required by law.

Gould and Lingenfelter then handed over text messages as well. Only Supervisor Jean Bishop, who voted against hand-counting, did not provide any messages in response to the request. She told Votebeat she didn’t have any text message discussions about hand-counting ballots.

The texts provided from Gould’s and Lingenfelter’s phones give a fuller picture of Borelli’s efforts there.

In early June 2023, Borrelli and Rogers went to a supervisors meeting and told the supervisors to vote to get rid of their voting machines on the grounds that they were insecure — though they didn’t offer evidence — and that the state Legislature had passed a nonbinding resolution banning their use. All supervisors except Bishop voted to have the elections director suggest a plan to move forward with hand-counting.

That included Johnson. But in group texts he was included in after the meeting, his own staff members mocked the idea.

“So did they vote to hand count???” one staff member asked.

“No to make a plan to hand count,” someone else replied.

“Oh for crying out loud,” the staff member responded.

On June 23, in a group chat, another member of Johnson’s staff wrote that “statistically hand counting is not possible … there is no logical way we can hand count the primary and general within the 14 day canvas[s] deadline.”

Another replied: “ha ha, well of course it won’t work, like going back to dial up internet.”

Asked why he voted for the plan if he didn’t support the idea, Johnson said he believed the board was going to vote to hand-count ballots. “The only way I could stop it was to suggest we have Allen come back with the cost associated with doing the hand count,” he said, referring to elections director Allen Tempert. “That would give time for the board members to think about what they were doing.”

Johnson said that he has publicly explained his reasons for not supporting hand-counting ballots, including a lack of problems with the current system, trust in the county elections director, cost, and the added time it would take.

If Republican state lawmakers wanted it to happen, he pointed out, they could have changed the law in 2022, when they had a majority in the Legislature and a Republican governor.

“We are an arm of the state,” he said. “We can only do what the state allows us to do.”

In August, Tempert presented his findings to the supervisors. He said a hand count of the 2024 election would cost the county more than $1 million, and require hundreds of workers and many weeks. Supervisors voted against the plan. Lingenfelter cast the deciding vote, saying it would be too costly.

Borrelli kept at it, though. In early November, he texted Lingenfelter and told him lawyer Bryan Blehm would be calling him.

“He’s the Attorney that will defend the County if it’s sued because of the hand count. ‘At no cost’ to the County,” he wrote.

After Lingenfelter and Blehm spoke, on Nov. 17, Lingenfelter texted Borrelli to confirm the vote would be on the Nov. 20 agenda. After Lingenfelter confirmed it, Borrelli sent him a smiley-face emoji with sunglasses.

That day, Votebeat published a story about the upcoming vote. That weekend, Mayes’ office sent a letter to Mohave supervisors warning them it would be illegal.

Lingenfelter sent Borrelli that article, as well as a related article in which Pinal County Attorney Kent Volkmer warned that Mayes could file criminal charges if supervisors moved forward.

“Criminal charges?” Lingenfelter texted Borrelli.

“That’s bullshit,” Borrelli texted back.

That day, Borrelli also texted Gould. “Please make the motion to approve,” he wrote. “And request a roll call vote.”

“I will,” Gould replied.

At the meeting, Lingenfelter again cast the deciding “no” vote against hand-counting.

Less than two weeks later, Mayes announced the indictments against the two Cochise supervisors.

In an interview, Lingenfelter said he had previously promised Borrelli he would put hand-counting back on the agenda if Borrelli found a lawyer who would make sure supervisors wouldn’t have to use taxpayer dollars for any legal costs associated with the effort.

He added that he ultimately voted no only because of Mayes’ threat to bring felony charges against supervisors personally, which he called “shocking.” If a court ultimately rules that hand-counting is legal, Lingenfelter said, he would vote in favor of using the method if that’s what most of his constituents want.

Johnson said he doesn’t know whether the county is done considering hand-counting.

“I guess it all depends on the results of the election,” he said. “When the election didn’t go the way people thought it should have, that’s when the problems came up.”

Pinal supervisors heed county attorney’s warning

Borrelli and Rogers had also tried to convince Pinal County’s supervisors to move forward with hand-counting. But just before the indictments, after the warning from the county attorney, they also rejected it.

At the request of the supervisors, the county’s election director began a hand-count trial in June 2023 using test ballots and found that each batch of 25 ballots was taking a team of workers about 87 minutes to count, or about 3.5 minutes a ballot.

In August, Borrelli and Rogers visited the supervisors and urged them to move forward.

Supervisor Mike Goodman’s office staff texted him before the meeting that they supported the idea. “Be bold boss! Hand count! Hand count! Hand count!” one said. “I say we stand up, stand out & lead on!!” another wrote.

The supervisors didn’t take action at that meeting. But months later they put an item on a Nov. 15 meeting agenda to discuss it again. That was when Rogers texted Cavanaugh and told him “don’t let them lie” about whether it was legal.

“By law, a 100% hand count can be done!” she wrote.

Cavanaugh texted her back. “I could not get any bos member to budge toward hand counts with volkmer talking grand jury indictments and pointing to ruling from appelate court,” he wrote.

Asked if Rogers influenced his thoughts on the topic, Cavanaugh said no. He said that he believes he and Rogers have a similar way of thinking, in that they are concerned about elections, but he also has to follow the law.

“I’m more cautious than a lot of people,” he said. “I try to base everything in law. So while I definitely support hand-counting, we have to do it in a way that is consistent with what the legislature has written and what the governor signed.”

Cavanaugh said that if it turns out to be legal to count votes by hand, and they can figure out a way to hand-count “accurately and speedily,” then he is OK with it.

“I don’t think the issue is dead,” he said.

Correction: July 16, 2024: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to indictments of Pinal supervisors. Peggy Judd and Tom Crosby are Cochise County supervisors.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.