Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

Out of the 13 propositions on Arizona’s ballot this year, Proposition 140 stands to have the greatest effect on the state’s elections.

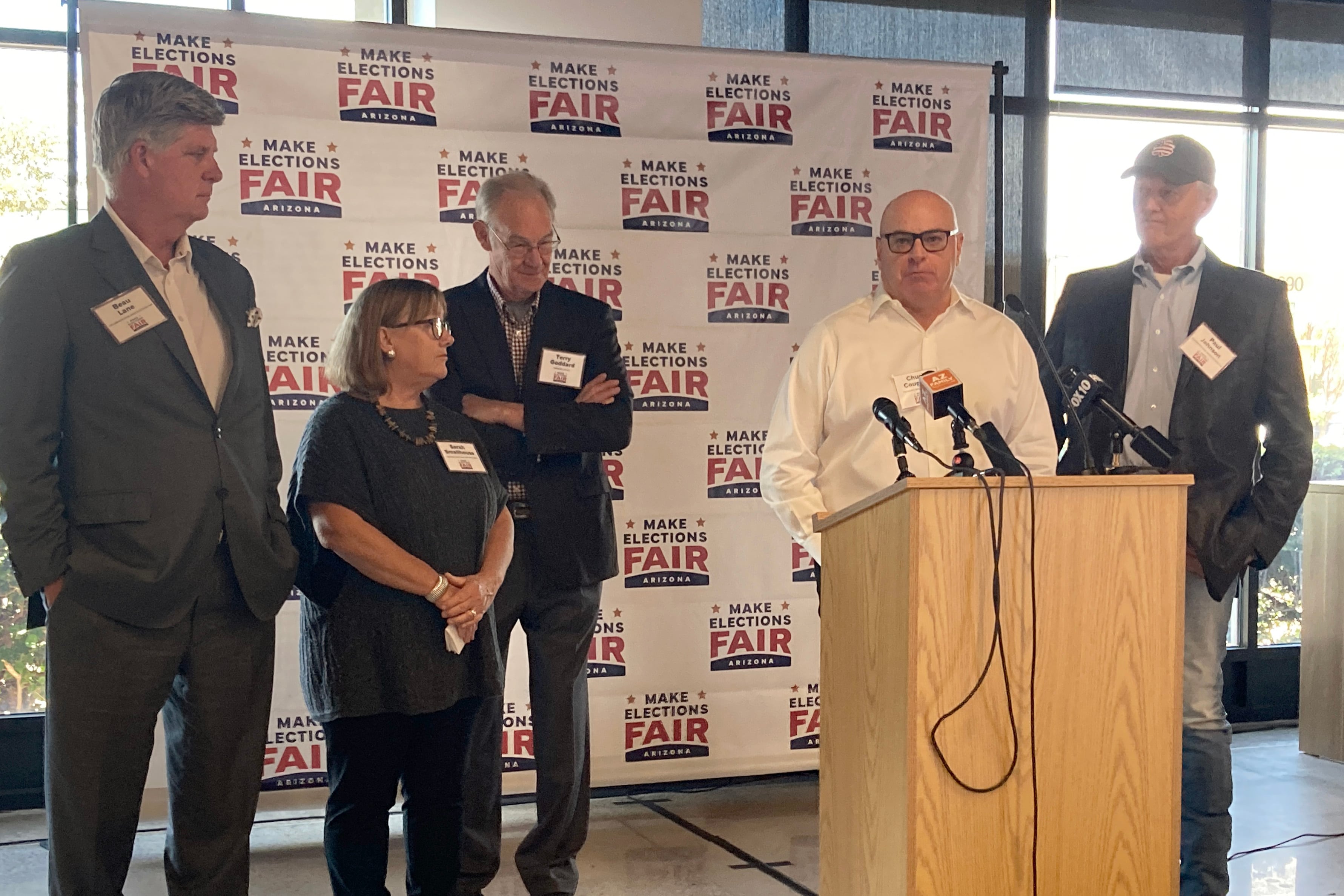

If approved, the Make Elections Fair Arizona Act would mandate open primary elections, ban the use of taxpayer money for closed partisan primary elections, and open up the possibility of ranked choice voting in general elections. Proponents and opponents have argued for months over how best to explain to the public what the proposition would and would not do.

The status of the proposition has been in limbo amid questions about whether proponents had collected enough valid signatures to put it on the ballot.

On Friday, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that the measure will remain on the ballot, and that votes for or against it must be tallied.

Here’s how each type of statewide election currently works in Arizona, and how a “yes” vote on Proposition 140 would change that:

Presidential preference election

Now: Arizona voters make their selections for presidential nominees every four years in a mid-March election called the presidential preference election. This is separate from the primary for all other offices. Taxpayers pay for the election, but not all voters can participate: Registered Republicans are allowed to cast votes only for Republican candidates, and Democrats can cast votes only for Democratic candidates. Voters who are not registered with a political party are prohibited from voting.

If Proposition 140 passes: Taxpayers wouldn’t fund presidential preference elections unless the parties agree to open them up to voters who aren’t registered with a political party, independent voters, and voters whose party won’t have a candidate on the November ballot; voters who are registered with a party that will be represented on the November ballot would still be able to vote only for their own party’s candidates.

If the parties don’t agree to open up their primaries, they would be required to fund their own presidential preference elections.

Statewide primary election

Now: Statewide primary elections are typically held in August each even-numbered year. (This year, the election was held in July, but that was a temporary change.) Each party holds its own primary election, funded by taxpayers, on the same day and under the same rules. Voters registered with a political party receive a ballot listing only candidates from their party to choose their nominees for the general election. Voters not registered with a political party, or not registered with a party that will be on the November ballot, can select any party’s ballot for the primary. If they are a mail voter, they must actively let the county know each election which ballot they would like to receive in the mail. Otherwise, they won’t be sent a ballot at all. Historically, voters not registered with a political party have had low turnout in primary elections, perhaps due to this requirement.

If Proposition 140 passes: The partisan primary system would be eliminated, but there would still be primaries to see who advances to the general election. All voters would receive the same primary election ballot, and all candidates from all political parties would run against one another. The election would be open to all voters, regardless of party affiliation, and including voters who are not registered with a party.

In races with one officeholder, voters would be allowed to choose just one name from the list of candidates. That list could include Republican candidates, Democratic candidates, and candidates from other parties.

The state Legislature would be required to enact a law by Nov. 1, 2025, deciding how many candidates would advance to the November general election. For a seat with one officeholder, such as for governor, lawmakers would set the number at two to five candidates. For a position with more than one officeholder, such as a state House seat — where each district elects two representatives — lawmakers would pick the number of candidates to advance, within the limits set by the proposition.

If the Legislature fails to enact such a law by Nov. 1, 2025, it would be up to the secretary of state to decide how many candidates would make the general election ballot.

The top vote-getters in the primary, regardless of their party affiliation, would advance to the general election. That means multiple members of the same party could be competing against each other in the general election. For example, if the Legislature decides that two candidates will advance to the general, and the top two vote-getters in the governor race are both Republicans, there would be no Democratic candidate on the November ballot.

Every six years, the Legislature would be permitted to change the law governing how many candidates advance to the general election.

Statewide general election

Now: Arizona operates under a plurality vote system in which the top vote-getter is elected. Even in contests with more than two candidates, the leader does not need to secure more than 50% of votes to win.

If Proposition 140 passes: How the November general election is run would depend on the law enacted by the Legislature governing how many candidates advance from the primary.

For a seat with one officeholder, if the Legislature decides that two candidates advance to the general election, the top vote-getter is elected. If the Legislature decides that three, four, or five candidates advance to the general election, the state would use a system called ranked choice voting, in which voters rank all candidates on the ballot in order of preference. For example, if there are three candidates for governor, the voter would mark their first, second, and third choices.

If one candidate receives more than 50% of the first-choice votes, that person wins the election. If no candidate gets more than 50% of first-choice votes, the procedures from there would be determined by the Legislature. In many ranked-choice voting systems across the country, the person who gets the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated from contention, and the state distributes that candidate’s votes by looking at voters’ second choices.

For a position with more than one officeholder, such as the House seats, the proposition allows state lawmakers to decide how the winner is determined.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.