Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

Arizona’s election system has been thrown into turmoil over the past four years by false claims of widespread fraud and some real instances of mistakes in running elections. Now, Republican candidates for county recorder across the state are playing up those false claims and errors as they try to get elected.

Their opponents acknowledge that Arizona elections can be improved, but warn voters to be wary of turning over crucial decisions about voting to candidates who seek to leverage distrust in the system.

The most closely watched race is in Maricopa County, where Republican state Rep. Justin Heap is running for recorder against Democrat Tim Stringham on a pledge to “secure our elections.” Heap defeated the current recorder, Republican Stephen Richer, in the August primary after claiming that Richer ran “the worst election in history” in 2022.

The competitiveness of these contests, and the rhetoric accompanying them, show just how much the role of the county recorder has changed since the last time the position was on the ballot, four years ago.

The recorder controls some aspects of voting, and other administrative duties, such as recording real estate transactions. In the past, recorders often served for decades without attracting much attention or controversy. But that changed in 2020, when a deluge of false election-fraud claims by Donald Trump’s allies, as well as a few real mistakes in election administration, fueled distrust among some voters.

Republicans with similar platforms to Heap’s — and using similar language — are running for recorder spots in Coconino, Navajo, Pinal, and Yuma counties. In Cochise, current Recorder David Stevens, another election skeptic, is running to defend his seat.

The county recorder races are among the most important on the Nov. 5 ballot, Secretary of State Adrian Fontes said in an interview, because he sees them as a showdown between the truth and lies. Fontes, a Democrat, offered a rare endorsement on Friday for Stringham in Maricopa County, writing that his race against Heap was a choice between “an honorable military veteran or an election denier.”

“This isn’t political,” Fontes said in the interview, “and I think that’s what people miss. It’s about the truth and about believing in reality.”

Recorders make decisions that directly affect voters, including how to clean the county’s voter rolls, where to put early voting locations and ballot drop boxes, and how many of each there should be. But in most counties, it’s up to county supervisors to oversee election day procedures and vote counting.

One exception is Pinal County, where the supervisors recently gave Recorder Dana Lewis, a Republican, control over the election department. There, Supervisor Kevin Cavanaugh has repeatedly questioned the integrity of the county’s elections, including in his own failed run this year for sheriff. After an $150,000 independent audit found no support for his allegations, Cavanaugh says he’s challenging Lewis as a write-in candidate for recorder.

The recorder position is in a period of unusually high turnover. The harassment and stress in recent years has forced a few longtime recorders out of the position, and helped convince others to retire. Meanwhile, the high profile of the role is now attracting people who are more comfortable in the public spotlight. This year, at least three of the non-incumbent Republicans running are current or former elected officials who have established campaign spending accounts and public reputations.

In Yuma County, for example, the GOP candidate is Republican David Lara, who ousted sitting Recorder Richard Colwell in the primary. Lara is a local school board member who has long worried about ballot trafficking and helped gather video that led to the conviction of two Democrats in connection with a ballot harvesting scheme during the 2020 election.

In Maricopa County, Heap vows full review of longtime staff

In Maricopa County, Heap is blaming Richer for technical problems voters experienced on Election Day during the 2022 midterm election, and suggesting he could do better.

“The plague of Election Day problems that we have seen in recent years must end now,” Heap said at a recent rally, also calling for election results to be finalized on election night.

As recorder, though, he would not have direct control over Election Day or ballot counting.

Heap has also accused Richer of failing to clean the voter rolls of people who have moved, saying during a primary debate that hundreds of voters told him they are receiving mail ballots for people who don’t live at their address.

Heap has not said what he would do differently to clean voter rolls. He didn’t respond to a phone call or text messages requesting an interview or an answer to that specific question.

Richer, who has fiercely defended the county’s election processes against a barrage of attacks from within his own party, declined to be interviewed for this story, but has said in the past that he follows all laws and that his office has been diligent and proactive about voter roll cleanup.

Federal and state law, and the state’s Elections Procedures Manual have detailed rules for how election officials must conduct all aspects of voting, including strict limitations on when someone may be removed from the voter rolls.

Under state law, for example, a county recorder can’t remove someone from the voter rolls who has moved from their address unless that voter notifies the county, registers to vote in another county, or goes two election cycles without either voting or responding to notices from the recorder’s office about undeliverable mail.

Still, Stringham said in an interview, the recorder controls the department’s budget and staff, and that can make a big difference in how the election goes.

Heap has said in a debate before the primary that if he is elected, he will conduct a full performance review of everyone working in the office, and the policies they follow. He signaled that he’ll push for personnel changes, saying many current employees were “hired under the radical Democrat Adrian Fontes,” and describing others as career bureaucrats.

In contrast, Stringham said he believes his biggest success will be retaining talent. He said that he doesn’t believe Heap has serious proposals on how to improve the county’s elections, but worries that Heap will damage good systems already in place.

“If I give a Lego Death Star to a 3-year-old, they probably can’t read the instructions and put the Death Star together,” he said. “But if I give a perfectly constructed Lego Death Star to a 3-year-old — yeah, any 3-year-old is capable of destroying that in a hurry.”

Yuma County candidate raises concerns about ballot harvesting

In Yuma County, Republican candidate Lara said he’s convinced that the illegal ballot harvesting he caught in 2020 is widespread, and not an isolated case. He said that he secretly monitored the county’s ballot drop boxes with cameras during the midterm to try to catch other instances, but that none were prosecuted.

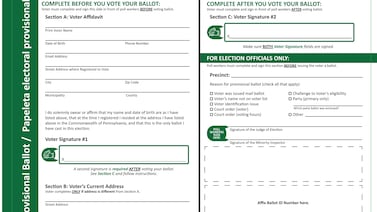

To combat ballot harvesting, Lara said he would use the signature verification process for mail-in ballots, rejecting any signature he did not believe was the voter’s signature. “That is a lot of power,” he said.

He said that while some media reports have described him a “conspiracy theorist” or “election denier,” he believes the 2020 case shows support for his assertions.

Xanthe Bullard, chair of the Yuma County Democratic Party, called Lara’s dropbox monitoring activities a form of voter intimidation, and said she expects more of that if he is elected. She said she believes he could use the signature verification process and voter roll purges as a way to unfairly target certain groups, such as Hispanic voters.

Lara dismissed those assertions, saying his hidden monitoring would not intimidate voters.

His Democratic opponent, Emilia Cortez, said she didn’t want to talk about her competitor’s activities or views. But she did say that she trusts the county’s election workers, after working as a poll worker in the past. She said she entered the race to protect the county’s elections and election workers and because she believes that she has the organizational background to develop better voting procedures.

“I want to be that bridge, that gateway, to reassure everyone that these elections in Yuma County are going to be valid and secured,” Cortez said in an interview.

Voter roll cleaning on the Republican platform

In other counties, too, candidates are alleging that voter rolls haven’t been properly cleaned, and in some cases, they’re echoing claims about noncitizen voting that have been circulating around the country. As they do so, they aren’t offering proof.

In Coconino County, for example, Republican candidate Bob Thorpe, a former state representative, wrote on his website that “Coconino County’s voter database has over 6,000 entries that have not been removed, some that are over 40 years inactive.”

Thorpe is running to succeed longtime Recorder Patty Hansen. Hansen said in an interview that Thorpe’s allegation is inaccurate, and she has tried to tell him that. Thorpe was looking at the incorrect inactive date, she said, and those voters are not eligible for removal.

Hansen said she is endorsing Thorpe’s opponent, Democrat Aubrey Sonderegger, to take her spot. She pointed out that Thorpe signed the joint resolution from the Legislature urging Congress to accept a slate of false electors in 2020. And she said she believes Sonderegger shares her commitment to “working toward having everyone’s voice heard.”

Thorpe didn’t return a phone call for comment. He says on his website that he will “protect voter rights for all Independents, Democrats and Republicans.”

(Update, Oct. 23: In a phone call after publication, Thorpe said he believes a full review of the county’s voter roll is important to ensure that no ineligible voters are voting, but stressed he doesn’t want to remove any eligible voters.)

In Navajo County, in northeast Arizona, Republican candidate Timothy Jordan says on his website that one of his top priorities is updating the voter rolls, which he claims, without providing evidence, include deceased voters and ineligible noncitizens. He’s running against incumbent Recorder Michael Sample, a Democrat.

Fontes said that although some recorder candidates might be advocating extreme policies, he believes their actions will be different if they win.

“I remember a certain county recorder race, when someone was going to come in and overhaul the system,” Fontes said, talking about when Richer unseated him as Maricopa County recorder in the 2020 election.

“He ended up supporting everything his predecessor did.”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.