The onslaught of first-time student voters who overwhelmed polling places at Michigan’s two largest universities on Election Day has officials looking for ways to avoid such severe backups in future elections.

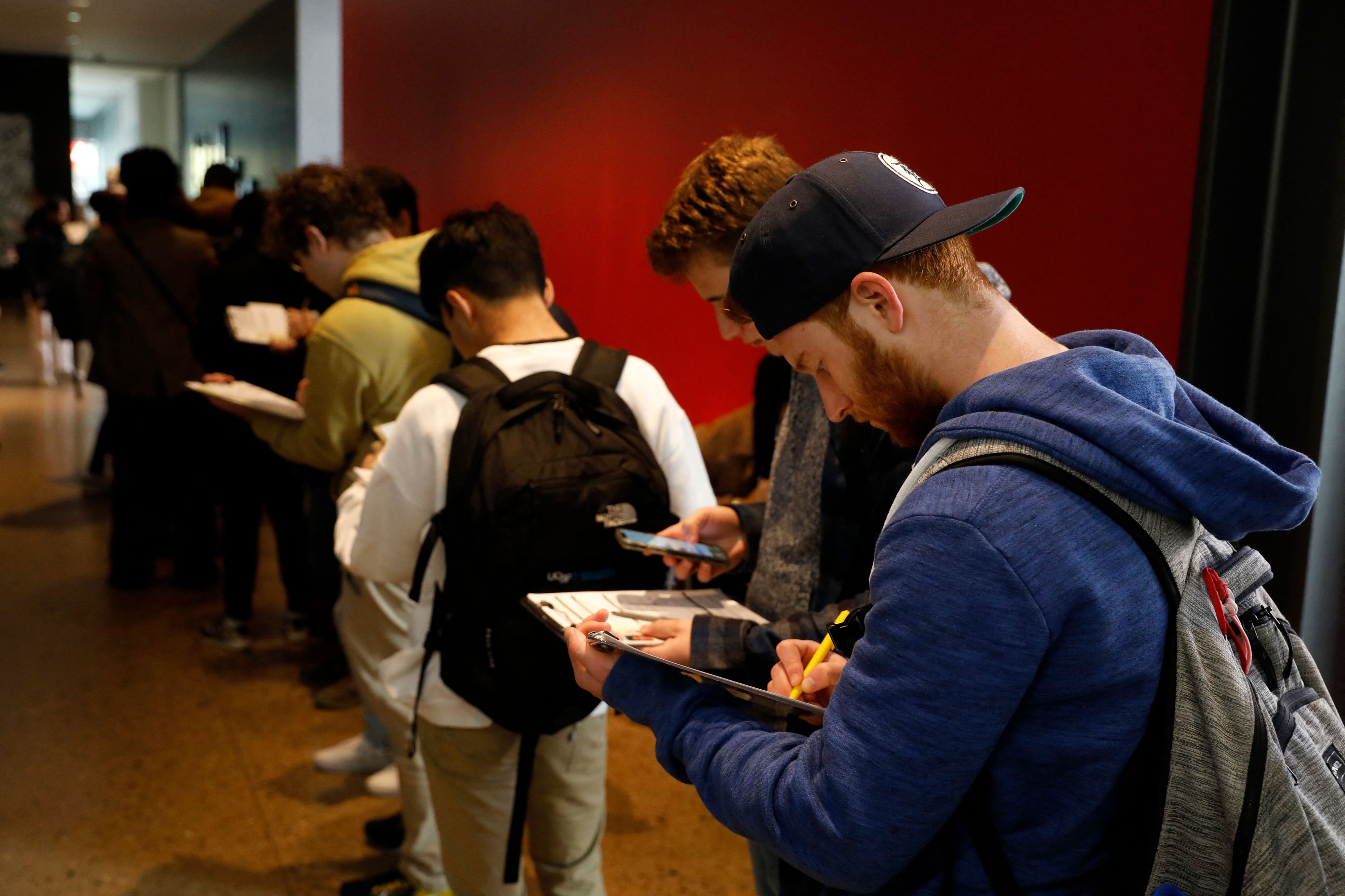

An unprecedented hundreds of students at the University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor campus and at Michigan State University in East Lansing crammed voting sites on Nov. 8. Many of those students were taking advantage of same-day registration, and some had to take an extra step to officially change their addresses — time-consuming processes that slowed down voting. The crowds meant winding lines and hours-long waits at the campus voting precincts, lasting into the wee hours of Wednesday morning, when the final ballot was cast at 2 a.m.

Some 4,000 University of Michigan students registered to vote on campus in the days leading up to Election Day. An additional 1,500 registered on that day, Ann Arbor city clerk Jacqueline Beaudry said.

Like the University of Michigan, MSU also saw droves of students turn out to vote.

MSU spokesman Dan Olsen said that 2,690 students voted in-person on Election Day. Some of those voters registered the same day. East Lansing Clerk Jennifer Shuster did not respond to phone calls requesting more detailed voting information.

While voting organizers and clerks were happy to see the huge turnout, they said they need to be better prepared by 2024 to avoid a repeat of the last-minute rush of student voters.

“We have more work to do in terms of how to get them to come earlier,” said University of Michigan art professor Stephanie Rowden, an organizer with groups that promote campus voting. “One of the coordinated efforts has to be in messaging. You have to remember many of them haven’t gone through this process before.”

Officials noted that although students were made aware a month and a half prior to Election Day of the opportunity to register and vote early, students did not take advantage of these options.

“We didn’t see a lot of interest until the last two days,” Beaudry said. “We were encouraged and excited to see so many students. Unfortunately we didn’t see a lot of pre-registrations,” she said, referring to a step that saves time when students show up to register and vote “It would have helped if more students chose to get registered early.”

Michigan’s ballot — with the hotly contested gubernatorial race and Prop 3, a constitutional proposal to outlaw a 1931 abortion ban — attracted wide student interest.

Since 2018, Michigan has allowed same-day registration, enabling many of these new, young voters to both register and vote on Election Day. Local election administrators attributed the high turnout to the same-day registration option, which takes more time than voting alone, fueling the growing wait times throughout the day.

While local election administrators in both areas say they tried to accommodate the voter traffic they expected, they’ll do more as 2024 approaches to prevent such delays. This year, both schools set up voting information for the students and worked with local election administrators to provide multiple opportunities for registration and voting.

Local administrators told Votebeat that they’ll hire more staff in future elections to deal with Election Day registrations. In Ingham County, where MSU is located, County Clerk Barb Byrum says the changes also should include improved technology and other resources such as funding, but Byrum did not say whether she will be asking for more funds for the efforts yet.

By the 8 p.m poll closure time on election night, there were about 375 students in line at the University of Michigan Museum of Art polling site and another 175 lined up at the Duderstadt Center, said Rowden, the art professor. Because those students were in line before the poll closure time, they were allowed to register if they needed to and cast their ballots.

The students “had a sense of humor and camaraderie” about the experience despite the long lines, said Rowden, adding that she was surprised and heartened by the turnout of the young voters.

“And they had a sense of appreciation for those of us working [the election],” said Rowden, who worked with a bipartisan coalition of campus and student organizations aimed at getting out the student vote.

“The fact that they stayed with us is evidence that they were excited about voting,” said Olsen, the MSU spokesperson. “We did our best to accommodate them. We were trying to make it as easy as possible to register and vote.”

Olsen said there was some confusion among students who had not changed their addresses to their college residences and had to do that before voting. Volunteers helped ferry them to another campus polling site, Brody Hall, where they could change their address and register to vote at one location.

Olsen said that while MSU’s turnout efforts were a success, he admits there “certainly are some things to revise and improve our efforts.”

Those who monitor youth voter turnout were encouraged by the enthusiasm. For Cheyenne Hunt-Majer, a Gen Z political activist and Washington, D.C., lawyer, seeing the lines of young voters looking forward to voting, in many cases for the first time, “made me real proud.”

“The outreach [groups] were doing on college campuses was tremendously effective,” said Hunt-Majer. “Those lines were such an indication that the message [to voters] was landing.”

But, the political activist cautions that long lines could be also a barrier to voting and democracy. Hunt-Majer said elections officials and colleges need to explore ways to make the “rite of passage” easier for voters, allowing them to be “part of democracy.”

Michigan State University and U-M Ann Arbor, and U-M Dearborn were among the nation’s colleges and universities applauded by the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge for efforts to get students engaged and active in voting.

Nearly 400 schools were chosen for their “most engaged” efforts in getting students to take part in voting. Fourteen other Michigan schools were recognized for their voting initiatives, including Wayne State University and Oakland University.

“The research is clear: colleges and universities that make intentional efforts to increase nonpartisan democratic engagement have higher campus voter registration and voter turnout rates,” Jennifer Domagal-Goldman, executive director of the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge, said in a press release Wednesday.

U-M pre-med graduate student Erik Pedersen, who cast the final ballot in the state at 2 a.m. Wednesday, voted at the museum polling place on the Ann Arbor campus after he’d waited in line for 6 hours.

“I was surprised by the long lines, as were many other students, but in retrospect we should not have been,” Pedersen said in an email. “Many of my fellow students felt very strongly about Proposition 3. It is my understanding that the majority of the student body voted in favor of the proposition.”

Pedersen, a second-year master’s student in microbiology and immunology, took the extended wait in stride.

“The event was a welcome distraction from my usual routine,” he explained. “Volunteers also gave everyone coats, blankets, hot chocolate, and pizza. Everyone seemed to be in good spirits overall.”

This article is made possible through a partnership with Bridge Michigan, Michigan’s largest nonpartisan, nonprofit news publication.

Oralandar Brand-Williams is a senior reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Bridge Michigan. Contact Oralandar at obrand-williams@votebeat.org.