Republican secretary of state candidate Kristina Karamo had something to say in Lansing on Monday as the Board of State Canvassers prepared to certify her loss, and she swore it wasn’t sour grapes.

The election, Karamo charged without evidence and with raucous protesters in the background, was “unlawful,” the certification process was “treason,” the incumbent secretary of state “refuses to accurately maintain our qualified voter file,” and she wanted the board to decline to certify the results.

The board’s chair, Tony Daunt, a Republican, was having none of it. Instead, he warned Karamo and the protesters against spreading “dangerous lies” he said the board would not tolerate, and chastised protesters’ behavior.

“We will ask for everybody to be polite,” warned Daunt. “If you have children, act like you would expect your children to act.” Despite his caution, police officers still had to remove a protester from the meeting. The man used expletives to refer to the board members as he was led from the room.

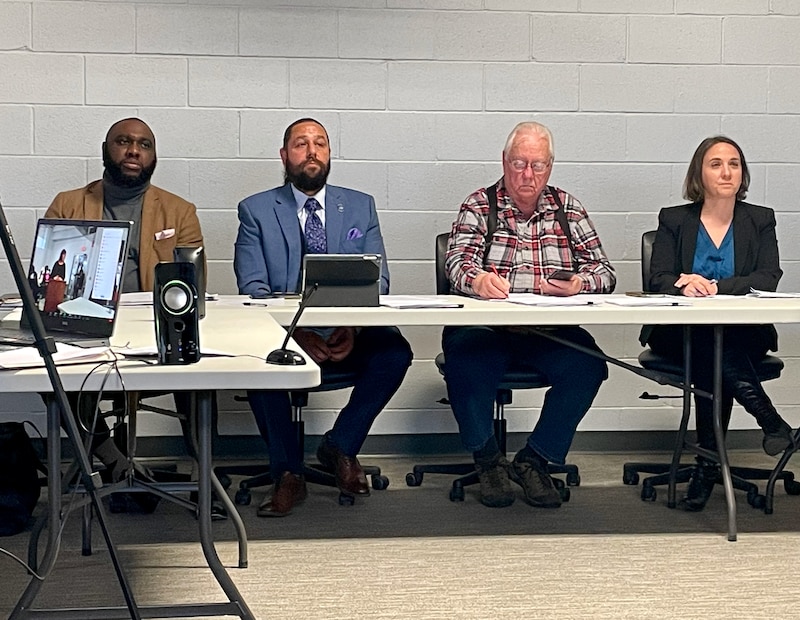

After four hours of belligerent but baseless objections, the four-member board unanimously declared the election results in Michigan final — and a host of state and local officials and watchdogs breathed a sigh of relief.

In 2020, some Republicans on canvassing boards resisted certifying the results, citing unfounded conspiracy theories about the election. Their reluctance highlighted the potential vulnerability of what had until then been a purely procedural step that drew little attention.

Many feared the problem could be even worse this year, after Trump-aligned Republicans were appointed to fill board vacancies. Instead, county and state boards finalized the results without any major stumbles, even as pitched battles over certification played out this week in Arizona and Pennsylvania.

And Michigan voters have now taken steps to limit the potential for mischief in future elections. During last month’s election, more than 60% of voters approved constitutional election reforms outlined in Ballot Proposal 2, known as Prop 2, which will virtually eliminate the threat of boards of canvassers interfering with election results.

“The board of canvassers is not an investigative body, and Proposal 2 makes it crystal clear that they are just to count the vote,” said Sharon Dolente, the adviser to the Promote the Vote coalition behind Prop 2.

A provision of the new law takes any suggestion of power away from the boards, codifying that a board of canvassers has a “ministerial, clerical, nondiscretionary duty … to certify election results” as reported by precincts and counties.

“We wanted to make sure it was enshrined in the state constitution and be based on nothing but the vote,” said Dolente.

Both the Wayne County and Michigan canvassing boards drew national headlines in 2020 after Republican members initially declined to certify the presidential election. Mobs of angry Republicans demanded that the boards toss votes from the city of Detroit and elsewhere in Wayne County.

Jonathan Kinloch, a former member of the Wayne County Board of Canvassers, remembers the contentious meeting in November 2020 during which two Republican members initially voted against certifying the election results.

This year was different. The atmosphere inside the room during the Nov. 22 certification vote was mostly placid, despite the din of demonstrators protesting outside. The board unanimously voted to certify results from the county’s 1,067 precincts.

Before voting to certify, Republican member Katherine Riley raised a concern with e-poll book errors in Detroit that complicated voter check-ins. Along with Democrats on the board, she pressed election officials about whether they had determined the cause. Michigan Elections Director Jonathan Brater had told the board on Nov. 16 that he was looking into whether the problems stemmed from glitches with laptops at the polling places.

“This is exactly how the process should work,” said Kinloch, a Democrat who is now a Wayne County commissioner. “I’m hoping this is normal” going forward.

The constructive questions made for a sharp contrast to November 2020, says Kinloch, when “the whole world was watching” as the Wayne County Board of Canvassers members Monica Palmer and William Hartmann, both Republicans, voted to not certify.

“We all knew there was nothing we could do,” Kinloch said of he and the other Democrat on the board. Under pressure, Palmer and Hartmann later reversed their decisions, voting for certification.

But until they did, certification hung in the balance, and people began to worry about what would happen this year. Those worries grew when local Republican Party officials who questioned the results of the 2020 election were appointed to fill vacancies on canvassing boards in Wayne County — where even Palmer was replaced — and elsewhere, including Macomb County and Genesee County.

Those hardliners include, for example, Nancy Tiseo, now a GOP-appointed member of Macomb County’s Board of Canvassers, who in December 2020 tweeted “DO NOT CONCEDE” with the hashtag #StopTheSteal” in response to a Trump tweet alleging that the 2020 election was fraudulent.

In Michigan, the two main political parties, Democrats and Republicans, each nominate three candidates for four-year terms on the county canvassing boards. County officials then appoint a member from each party’s slate. The board is made up of two Democrats and two Republicans.

Palmer’s replacement on the Wayne County board, Robert Boyd, said last year when he was appointed that he would not have certified the 2020 results. Boyd said he believed the results “were inaccurate.”

Before this year’s election, however, Boyd told Votebeat Michigan he would perform his duties solely based on the rules.

“The idea is even if the county board of canvassers found things that are wrong, we cannot correct them. We have to turn that over to the prosecuting attorney of Wayne County, and it’s up to them if they want to look into it or not,” said Boyd.

State board accepts its “ministerial” duty

Boyd isn’t the only new GOP member of a canvassing board who initially raised concerns before signaling he would move ahead and finalize the election. The new Republican members of the state board, including Daunt, sparked concern earlier this year when it deadlocked over allowing two proposals to appear on the November ballot, including Prop 2 and also Proposal 3, intended to repeal a 1931 state ban on abortion.

On the voting reform proposal, the Republican members argued that the language was hard to understand and full of mistakes. On the abortion proposal, the GOP canvassers complained about spacing of words in the petition language.

In September, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered the state board to approve Proposals 2 and 3 for the ballot. And by October, the board members were clearly acknowledging that they were obligated to certify the results that were presented to them.

During an Oct. 26 media briefing with election officials, Daunt reminded local canvassing boards that county canvassing boards have a “ministerial” duty to certify the vote. “Math is the key here,” said Daunt. “Making sure that the number of people who have shown up … that the tapes [from the counting boards] match those numbers.”

University of Massachusetts Amherst political science professor Amel Ahmed, an expert on democratic institutions and the electoral process, was among those who worried before the election that Republicans who believe the 2020 election was stolen could cause problems in certifying election results.

“There is a concern that the attempts to put people in place that will interpret the rules and use their discretion of one political party over the other,” said Ahmed who stressed she did not know the new members of the canvassing boards in Michigan or their intent.

But Ahmed was confident that the end result would be as voters wanted.

“We have resources,” said Ahmed, referring to the court system. “We have a very strong democracy. There are lots of [individuals] who have power and the fortitude to push back.”

With the passage of Prop 2 — a solution, Ahmed said, that creates “more rules to fill in the gaps and less room for discretion” — Michigan has now learned that the individuals who have the power to push back are the voters themselves.

Oralandar Brand-Williams is a senior reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Bridge Michigan. Contact Oralandar at obrand-williams@votebeat.org.