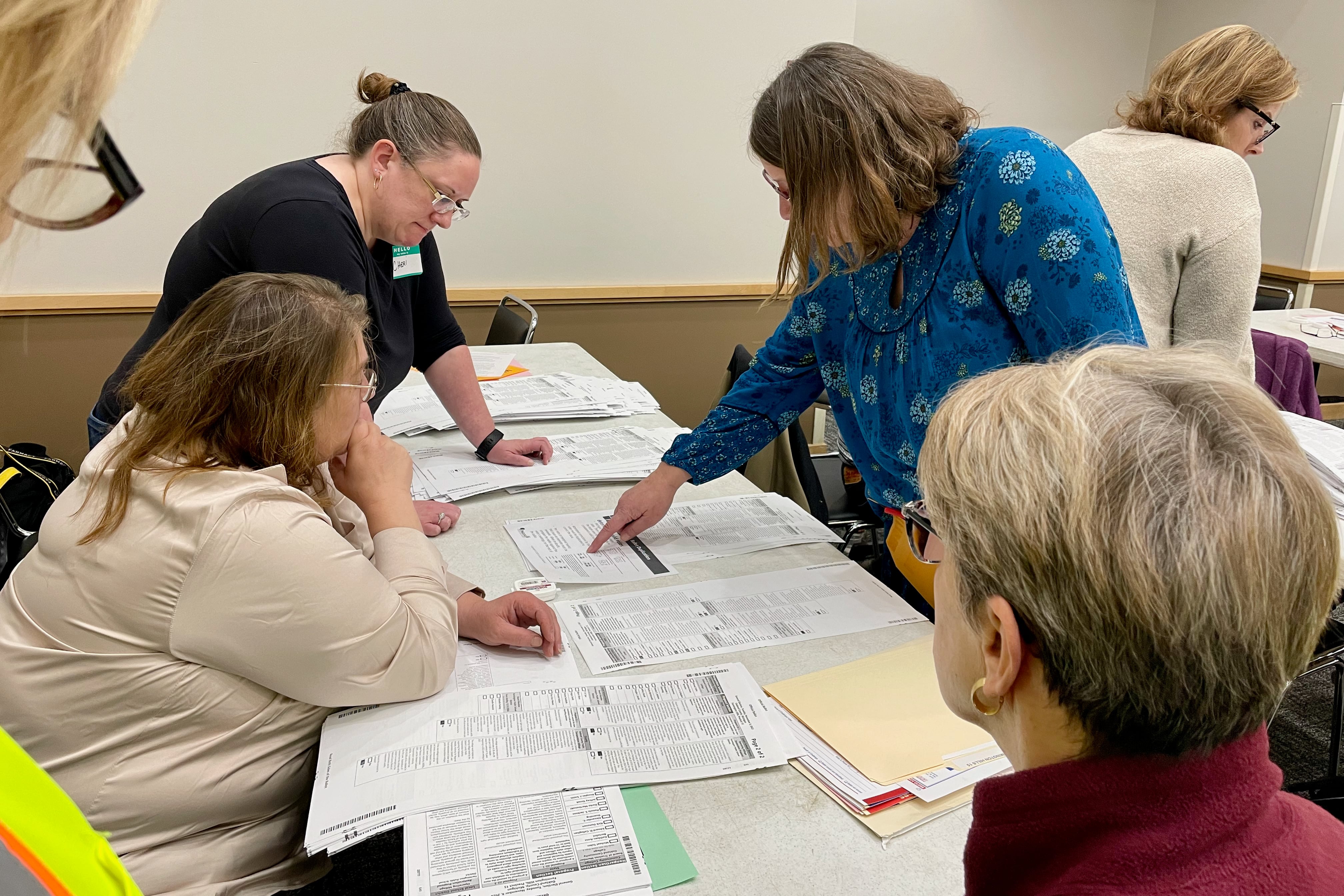

On the first day of a recount in 47 counties around Michigan on Wednesday, the auditorium of the Troy Community Center in Oakland County was filled with the sound of shuffling papers and restrained chatter. The county clerk, wearing a bright yellow safety vest, paced through rows of tables, checking on her election workers as they were inspecting and counting ballots.

From Detroit to the Upper Peninsula city of Marquette, election workers this week and next week are re-tallying the votes cast on two proposals that were on the November ballot: Prop 2, a set of voting reforms, and Prop 3, which ensures a constitutional right to an abortion.

The recounts are being conducted in more than 500 precincts at the request of a petitioner for the Election Integrity Fund and Force, a nonprofit and nonpartisan group based in Oakland County that recruits poll challengers and says it seeks “transparent and trusted” elections.

The group invoked a little-used provision in state law to trigger the recount, even though the two ballot proposals were approved by a margin that makes changing the outcome a near-impossibility, and is paying with money from prominent boosters of election conspiracy theories. Election skeptics are making similar requests in other hotly contested states, slowing the process of finalizing election results and prompting calls from advocates to change laws they say are being abused in ways lawmakers didn’t anticipate.

In Troy, workers from the Oakland County Clerk’s office brought in storage containers, resembling suitcases, full of ballots from 95 precincts to start the recount at 8 a.m. “Recountable,” workers announced from some of the 100 counting tables as they checked the security of a ballot container and matched the ID numbers on its security seal with the number written in the poll book on Election Day, all part of the measures to ensure a precinct is eligible for the recount. Officials determined five precincts were ineligible for recount for such reasons — not enough to change the outcomes of Oakland’s final count, according to Oakland County Clerk Lisa Brown.

Elsewhere, the process appears to have been less placid. By Wednesday night, Attorney General Dana Nessel announced there had been “reports of threatening behavior and interference” at some of the recount sites, without specifying where the incidents had happened or who was involved.

In an interview Friday, Sandy Kiesel, the executive director of EIF, said her volunteer challengers filed a police report in Jackson County and in other areas doing recounts when challengers were rebuffed on their requested access to ballots. Challengers, she said, are looking for errors on ballots and ballot boxes and reasons that precincts would be ineligible for recount. Kiesel said challengers had reported concerns, but she wasn’t able to detail their evidence.

The group also released a statement Wednesday night claiming without evidence that the first day of the recount revealed “evidence of ballot box tampering.” The group didn’t provide any specific details on those allegations.

“What are we doing it for?”

On Wednesday inside the Troy Community Center, there were about 15 challengers among the 50 election workers. Troy resident Kathleen O’Laughlin was among those who answered EIF’s call to act as a challenger, because, she said, she didn’t like the outcome of the election.

O’Laughlin sat at one of the tables as a pair of election workers fastidiously looked for irregularities or mistakes on the ballots. Workers had found none as of early Wednesday.

“So far, it’s going like how I would do it,” said O’Laughlin about the recounting process and the diligence the workers demonstrated.

But O’Laughlin also wondered why there weren’t more challengers and whether the recount truly makes sense.

“If it’s not going to overturn the election, then what are we doing it for?” O’Laughlin said.

On Tuesday, EIF held an online “training session” to recruit and prepare challengers to observe the process and look for ballots that they say would raise suspicion of fraud.

Volunteer challengers watched a video, produced by the Oakland County Clerk’s office, instructing challengers on their role during recounts. Election Integrity Fund and Force leaders also told volunteer challengers to look at the entire ballot, front and back, and inspect it for smears and other marks that would provide a reason to file a complaint and potentially invalidate the vote.

But at the recount in Troy, state and county election officials instructed challengers and election workers to look only at the part of the ballot dealing with the partial recount — the votes on Prop 2 or Prop 3.

Jerome Jay Allen, an EIF member, filed the recount petition. His filing based the request on suspicion of fraud, voting machines allegedly not being certified or recertified by the federal government, and tabulators being connected to the internet, all claims that have been debunked by election and law experts. Nonetheless, the petition met the requirements set by state law and Allen was willing to put up the required funds, so officials had to approve it.

Before approving the recount requests, the chairman of the Michigan Board of Canvassers, Tony Daunt, called Allen’s effort “frivolous” and a “fishing expedition.” Mathematically, the recount stands no chance of changing the outcome of the proposals’ passage. Prop 2 passed by more than 860,000 votes and Prop 3 by more than 580,000 votes.

Costs will exceed group’s recount fees

The cost of the recount filing is being financed by the America Project, a group run by Patrick Byrne, the founder and former CEO of Overstock.com, and former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn, who believe the 2020 election was stolen from President Trump and have financed other efforts to find weaknesses in the election system.

County clerks across the state say that although Allen paid a fee for costs of the recount — $125 per precinct, according to the secretary of state’s office, which adds up to $62,000 to $75,000 — taxpayers will still end up picking up some of the tab.

Brown, the Oakland County clerk, said the recount “is not the best use of taxpayers’ money if you ask me.” Brown is still working with the state to calculate what Oakland’s final cost will be.

Brown says the recount is “frustrating” because it adds to the “misinformation and disinformation” around Michigan’s elections. “It makes people not trust our process,” Brown said, arguing the recount organizers’ accusations about voting equipment glitches changing the outcome is “wrong” and “inaccurate.”

In Ingham County, Clerk Barb Byrum wrapped up her recount Thursday of 86,000 ballots, which will cost taxpayers $8,200.

“This was not my first recount, but I’ve never done one for such a large margin [of the vote],” Byrum said Thursday.

Byrum said she had to hire 42 additional election workers and use the Ingham County Fair’s Community Building in Mason to work through the ballots from 38 precincts.

Byrum took to Twitter Wednesday and explained the recount procedure, warning challengers to keep their hands to themselves and not touch anything when they come in to observe the recounting.

Byrum said Thursday’s recount went smoothly.

Challengers “were on their best behavior,” said Byrum. “No one was allowed to touch anything.”

Ed Golembiewski, the Washtenaw County deputy clerk and election director, also said taxpayers will have to foot the costs of the extra staff he’s bringing in to help. He estimated the county will need to pay $6,000 to $10,000 on top of the $11,000 reimbursement it will receive from the recount filing.

Golembiewski will oversee 60 temporary election workers for the recount of 88 precincts, running Monday through Wednesday at the Washtenaw County Learning Resource Center in Pittsfield Township.

While the recount will come at a financial price to many counties, election officials like Golembiewski and Macomb County Clerk Anthony Forlini said there is no way around it.

“We are legally obligated to do it,” said Golembiewski. “We will of course oblige and do our job. But it is next to impossible that the recount will overturn the election.”

“It’s going to cost. I don’t know what that number is, but it’s our job to get the job done,” said Forlini. “If they want a recount, that’s their right.”

Macomb County is hiring 40 additional workers to help Forlini’s four-person staff with the recount, which will take place Monday, and possibly Tuesday, at the south campus of the Macomb County Community College. All recounts must be complete by Dec. 18.

Election workers will examine 19,000 ballots, said Forlini, who doesn’t expect any errors to be found.

“I believe in my heart and soul and would be surprised if there would be changes in over 10 votes,” said Forlini. “I just want a good, accurate and efficient recount.”

Responding to criticism that the recount is a waste of money, Kiesel of the EIF said, “this is a pretty good use of taxpayers’ money. The question should be why was this election certified.”

Michigan State University law professor John Pirich said the granting of the recount request points to a need for the Legislature to change the laws that allowed it to proceed. Activist groups are misusing legitimate election laws intended to verify accurate results in closely contested elections to instead “satisfy these theories and conspiracy ideas that people are throwing around without any facts or any basis whatsoever,” said Pirich.

“This is just a folly,” he said, “and the legislature needs to step up quickly to address these kinds of abuses of the election code.”

David Goldman, regulatory counsel for the organization Informing Democracy, agreed, explaining that the organizers were able to use a little-known provision of the Michigan election code that permits a voter, rather than a candidate, to seek a recount.

“I don’t believe this portion of the [election] code has been used before in recent cycles,” said Goldman, who has studied Michigan’s election system and laws. “Going forward, one thing we would like to suggest … is that the legislature or election officials revisit this part of the code and make sure that there are specific thresholds to meet going forward.”

This article is made possible through a partnership with Bridge Michigan, Michigan’s largest nonpartisan, nonprofit news publication.

Oralandar Brand-Williams is a senior reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Bridge Michigan. Contact Oralandar at obrand-williams@votebeat.org.