As the midterms approach, the Michigan secretary of state’s office has found itself repeatedly defending the state’s election system against local clerks. Experts say the clearest vulnerability facing Michigan are such insider threats, which the secretary of state has little ability to proactively prevent. The problem became most evident after a handful of local clerks last year allegedly gave people unauthorized access to election equipment, forcing the secretary of state’s staff to manage the fallout.

Now at least one of those clerks is making false claims about the state’s voting machines and hinting she may conduct the election without them.

Michigan is among the closest watched midterm battlegrounds, and the allegations that clerks in Barry County’s Irving Township, Missaukee County’s Lake Township, and Roscommon County, and a supervisor in Roscommon’s Richfield Township, allowed pro-Trump actors to have unauthorized access to tabulators last year sent shockwaves through the state.

Experts and state officials agree that there has been no lasting damage to the state’s voting systems, because the protective measures in place worked. But Michigan’s decentralized election administration means the first line of defense in election security are the 1,609 county, municipal and township clerks, who are responsible for overseeing and protecting equipment and following the law — or not.

The widely disseminated responsibilities make it difficult for the state to ensure that the rules are consistently followed. While there is no indication that other clerks have allowed unauthorized access and several interviewed for this story vowed to keep the machines secure, elections security consultant Ryan Macias said insiders willingly providing access remains “the biggest risk to security.”

One of the powers the secretary of state can exercise to ultimately hold defiant clerks accountable is to restrict their duties, according to John Pirich, an election law attorney and adjunct law professor at Michigan State University.

“The secretary of state can revoke a local clerk’s authority and take over their elections responsibility,” Pirich said. The State Department’s Bureau of Elections has done so at least twice in unrelated cases in the past year.

A recent round of warnings to clerks in the four places that experienced breaches showed that Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson is ready to use that power to protect tabulators. In letters dated Aug. 26, 2022, state elections director Jonathan Brater warned clerks not to allow more unauthorized access to their election equipment.

The letters to Irving Township Clerk Sharon Olson, Lake Township Clerk Korinda Winkelmann, and Roscommon County Clerk Michelle Stevenson instructed each clerk to check in with state officials monthly from September to January “to provide confirmation” that they have not allowed any unauthorized individual to have access to their election equipment.

“If you fail to provide these confirmations, you will be instructed to refrain from administering any elections and legal action will be taken as necessary to enforce this instruction,” Brater wrote to those three clerks. “Be advised that willfully failing to comply with a lawful order from the Secretary of State is a misdemeanor.”

A secretary of state spokesperson said Thursday that Olson, Winkelmann, and Stevenson did confirm by Sept. 2 that they had not provided additional unauthorized access. Richfield Township Clerk Greg Watt, who has not been found responsible for allowing access to Richfield’s tabulators, was not asked to check in periodically.

In total, five tabulators were released early last year to unauthorized officials and pro-Trump activists who dispute the outcome of the 2020 election. They were returned in varying conditions. One of the tabulators had been subjected to “extensive physical tampering,” said Deputy Attorney General Christina Grossi in an Aug. 5 letter regarding the case.

Several people — including Barry County Sheriff Dar Leaf, GOP Michigan attorney general candidate Matthew DePerno, and Republican state Rep. Daire Rendon — are under investigation for allegedly tampering with voting machines, a felony, in connection with the breach. A special prosecutor, Muskegon County Prosecutor DJ Hilson, was assigned to the case this month, though no charges have been filed.

It’s still unclear why clerks or other officials allowed unauthorized access to their tabulators. Winkelmann and Watt did not return phone calls and email messages seeking comment. Stevenson declined to comment. Olson issued an eight-point media statement to Votebeat containing several false claims about the security and certification status of the state’s voting systems, but otherwise declined to respond to questions.

Olson’s claims are concerning to officials because she also alludes to the possibility of counting ballots by hand this November, whereas Michigan state law requires the use of tabulators to count votes.

How “chain of custody” procedures help detect breaches

The rest of the state’s clerks, for their part, aren’t “freaking out” about the breach and equipment security, said Harrison Township Clerk Adam Wit, who’s also head of the Michigan Association of Municipal Clerks. Wit said Michigan’s “chain of custody” requirements for election equipment create a “nice paper trail” that allows officials to determine responsibility for a breach, and he — unlike the clerks in the aforementioned places — would flat-out deny any unauthorized request for access.

Experts and local clerks say that the tabulator debacle, perhaps ironically, has shored up their confidence in Michigan’s existing procedures and heightened their sensitivity to possible threats.

“If someone attempted to tamper with the election equipment, it would be evident,” said Washtenaw County Elections Director Ed Golembiewski, who partners with clerks from the county’s 26 cities and townships, including Ann Arbor, to run elections. “In Washtenaw, I know the clerks follow the rules.”

The rules Golembiewski refers to — which he said the secretary of state’s office has “made clear” — are specific chain-of-custody guidelines for protecting the election equipment. They require clerks to continually log the movements and status of each machine as well as who has been given access to them, and secure each piece in such a way as to make unauthorized access immediately apparent.

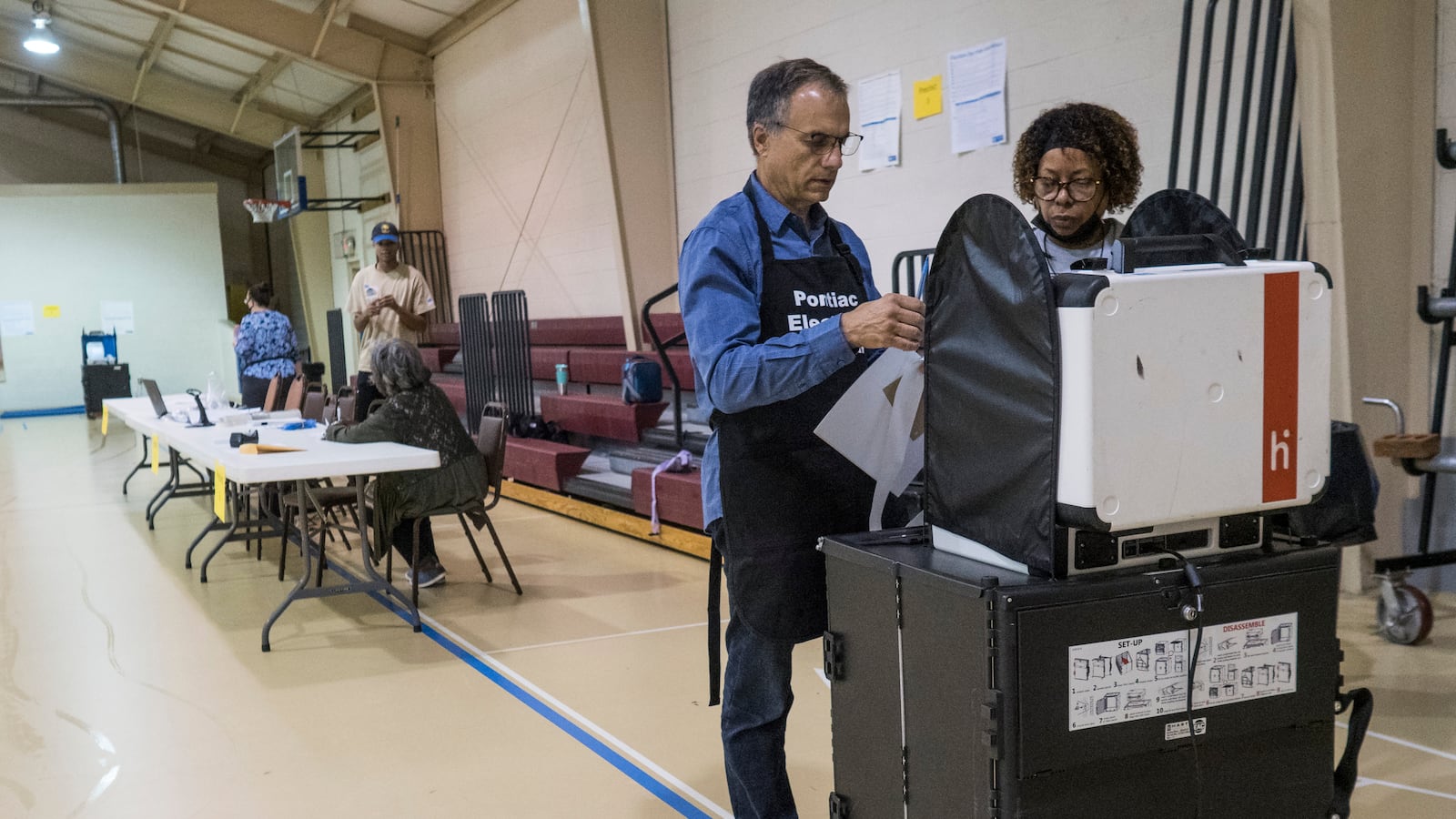

State policy restricts the handling of voting equipment and tabulators to the clerk, deputy clerk, elections staff, and employees from the companies that manufacture and service the machines. Each machine is outfitted with a tamper-evident seal and assigned a number that must match existing records. On Election Day, the tabulators are transported and put into use under the supervision of representatives from both the Democratic and Republican parties.

At each transfer point, those responsible for the machines must verify the condition of the seal and the machine’s number. The tabulators are sealed, usually with heavy-duty plastic, which is only broken at the end of the day when the USB drives containing the final count are removed and transported to the clerk’s office. If the seal is broken prior to that time, county and state authorities would be notified and would be able to immediately understand which employee had allowed unauthorized access and to how many pieces of equipment.

Given the detailed logs and protective sealing, state officials were able to respond quickly last year to the release of the equipment by the affected offices. Not only could they tell which employee had last accessed them, they could ensure that no tabulators beyond the five identified had also been tampered with, according to Macias and eight local clerks Votebeat interviewed.

Macias said the chain of custody logs allowed the state to immediately address any lingering security concerns and quickly identify the breadth of the problem. “There were protective measures in place,” he said in an interview. “All of these have been a success.”

Likewise, a recent unexplained incident in which a voting machine from Colfax Township in Wexford County apparently ended up for sale on eBay shows that equipment can go astray despite the procedures. Any chain of custody documentation will be crucial in the Michigan State Police investigation into how the voter assist terminal, which is used to help voters with disabilities mark a ballot, went missing.

Angie Cole, the deputy clerk for the Michigan/Indiana border town of Niles Charter Township, said that last year’s tabulator breaches caused her to reaffirm her commitment to the process already in place under law.

“No one gets access to these machines but me and [the clerk],” said Cole, who said she would personally supervise any court-ordered access. “They’re under lock and key 24 hours a day.”

How the law restricts access to tabulators

Under Michigan law, it is a felony for unauthorized individuals to tamper with voting equipment or for anyone to conspire with someone to do so, and once unauthorized access is allowed, the machines must go through an expensive, lengthy process before being put back into use, if they can be reused at all.

“Granting access to election equipment to unauthorized persons may result in the decertification of equipment or require additional procedures be followed prior to the use of such equipment,” Michigan Elections Director Jonathan Brater wrote in an August 2021 memo to clerks following the various attempts to examine election records or equipment.

Leaf, the Barry County sheriff who’s under investigation, told a Detroit News reporter last week that the clerks who handed over tabulators have the authority to do so under Michigan election laws.

Leaf reiterated those claims in a brief conversation with Votebeat Michigan, saying, “When they suspect voter fraud, they’ve got very broad powers.” Asked what section of state law gives clerks those powers, Leaf emailed a citation for a statute that addresses suspicions of illegal voter registration, not access to voting equipment.

Former Michigan elections director Chris Thomas says the sheriff’s comments have no legal basis.

“He’s wrong. If he can read English, then he knows he’s wrong,” Thomas said. “There is no connection between [Michigan laws] on voter registration and tabulators.”

Thomas said clerks who have questions about the law’s restrictions on access to election equipment should check with the state Bureau of Elections. “A prudent clerk would make that inquiry if they can’t make the legal justification” for handing over a tabulator to an unauthorized person, Thomas said.

Penalties for election officials who ignore the state’s election security rules could be severe, said Tracy Wimmer, a spokesperson for the secretary of state. “In instances where we learn of someone breaking the law we refer them to the attorney general’s office and local law enforcement for investigation, and, in certain instances, exercise supervisory control over the jurisdiction,” she said.

Typically, the secretary of state will only exercise such supervisory control if there is documented criminal behavior or a clear commitment to ignore rules and procedures. This year, the office stripped authority from the Genesee County clerk after he was charged with intimidating a witness and willful neglect of duty. In Adams Township, a clerk who had posted QAnon memes was blocked by the secretary of state’s office from running elections after refusing to allow a voting equipment vendor to perform routine maintenance in violation of state law.

Thomas says such drastic measures have been rare until now.

”[There’s] never been a reason to do what has been done this year because clerks did not intentionally violate the rules or security surrounding the voting equipment,” he said.

Thomas said that state officials need to stress that they “view it as illegal” for clerks to defy the rules around equipment security. Clerks also need to be reminded, he said, that if there is a breach, their jurisdiction will be responsible for replacing the tabulator, which can cost $5,000 to $7,000.

“The [special prosecutor’s] investigation can be a deterrent to future breaches,” Thomas said.

Clerk’s claims easily debunked

Olson, the Irving Township clerk, is beginning to represent a problem beyond tabulator security as she spreads what experts say is election misinformation from her position as an election official and as a lawsuit plaintiff.

Olson’s recent media statement falsely claims that Michigan voting systems were not reviewed by federally accredited test facilities, incorrectly concluding the 2020 election results should not have been certified. Olson and conservative groups made similar claims as part of a federal lawsuit filed this month, when they asked a judge to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

They also asked for a temporary restraining order, requiring the secretary of state and others to preserve records relevant to the case. Judge Paul Maloney of the Western District of Michigan denied the request in short order.

“The Court concludes Plaintiffs are not likely to succeed on the merits of their claim,” he wrote. “Plaintiffs were able to cast a ballot for their electors of choice and their votes were counted. Plaintiffs have not pled facts to show that their votes were canceled, diluted or nullified.”

The judge also expressed doubt in the facts presented by Olson and her allies. Experts and state officials say Olson’s statements and the arguments in the lawsuit are easily debunked.

For example, on the question of federal certification, Michigan law does not require machines themselves to be certified by a federal agency, as Olson claims it does. Instead, it requires that machines be tested by such laboratories and approved for use by the Board of State Canvassers, which they are. “All tabulation machines used in Michigan are certified by the bipartisan board of state canvassers, and tested by federally approved test laboratories,” said Jake Rollow, a spokesman for the secretary of state.

Matt Masterson, former head of election security for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, said that Olson has a “fundamental misunderstanding” of how the certification process works.

Likewise, Macias, who previously oversaw the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s voting equipment certifications, said the concerns levied by Olson and the lawsuit she’s filed are “inaccurate,” which he said makes her statement “misinformation or disinformation, depending on Ms. Olson’s intent.”

Rumors have been circulating about Michigan’s certification status since 2021, Macias said, and both the state and the U.S. EAC have previously addressed it. The EAC responded to the misunderstandings about testing labs last year with an online clarification to its processes. As an elections official, Olson would have received these clarifications. Her township also would not have been able to purchase any machine the Board of State Canvassers hadn’t approved for use. Her equipment was unanimously approved for use by that board in 2019.

Rollow declined to comment for the secretary of state on the group’s lawsuit. “We do want to remind Michigan citizens that meritless lawsuits have been used to gain media attention and mislead citizens by spreading election misinformation,” he said.

This article is made possible through a partnership with Bridge Michigan, Michigan’s largest nonpartisan, nonprofit news publication.

Oralandar Brand-Williams is a senior reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Bridge Michigan. Contact Oralandar at obrand-williams@votebeat.org.