Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Michigan’s free newsletter here.

Every other August in Michigan, thousands of votes are rejected because the voters didn’t pay attention to the directions on their primary ballot, or didn’t understand them.

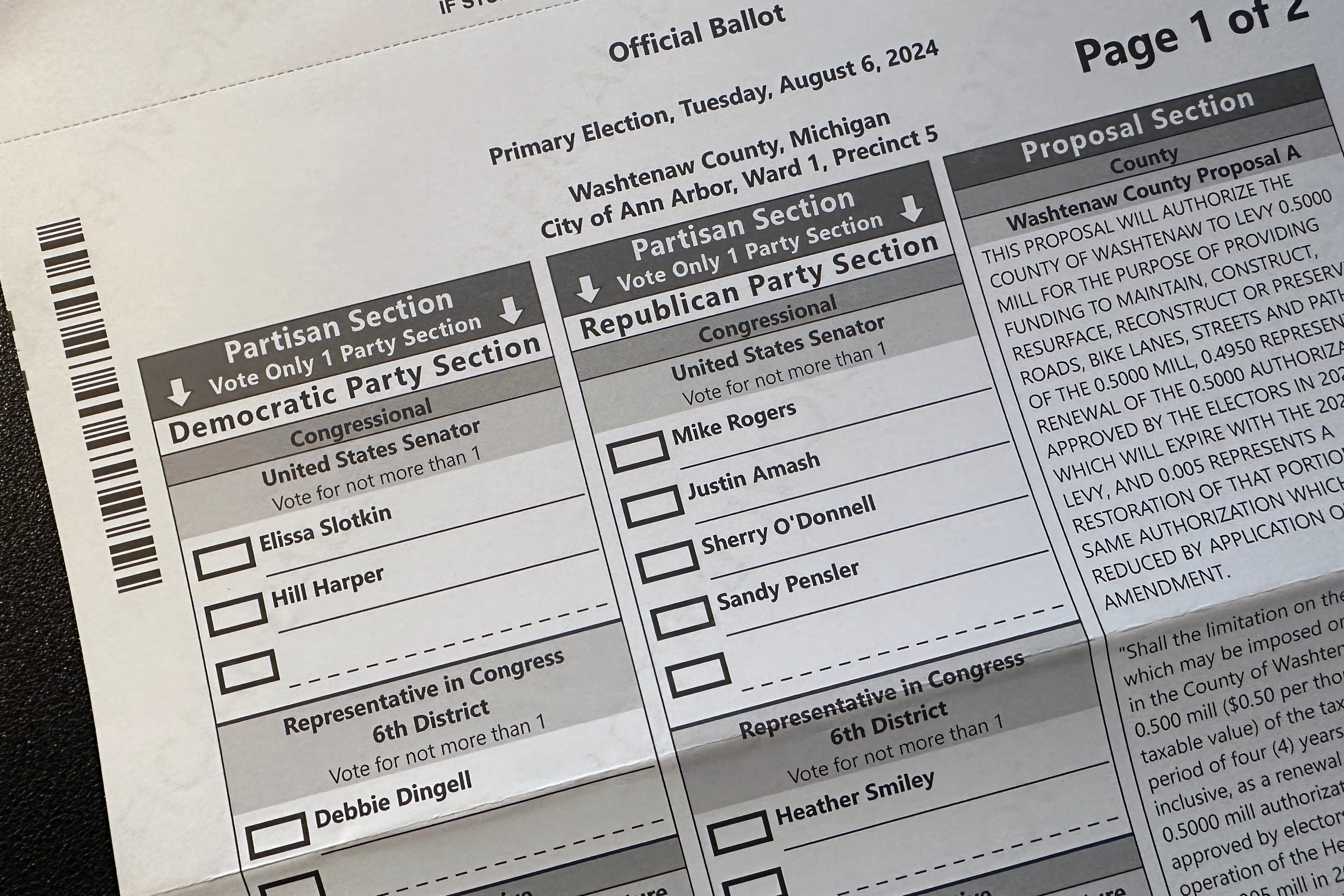

The problem occurs when voters do something called “crossover voting,” where, intentionally or otherwise, they vote for candidates from different parties on the same ballot. In a general election, that would not be a problem. And in a presidential primary, it wouldn’t be possible.

But in the August primary elections — where candidates for federal- and state-level positions are selected — a crossover vote that doesn’t get caught by the voter means officials can’t count the votes on the partisan section of the ballot. And many voters, particularly if they vote absentee, will never know that their partisan votes didn’t count, if they’re not around or don’t respond when their ballot gets flagged by the tabulator.

“I think that sometimes, it can be a source of confusion,” said Elizabeth Hundley, Livingston County Clerk.

It’s difficult to tell exactly how many crossover votes are cast in Michigan’s August primaries — the state doesn’t keep track of the number, and neither do many of the counties Votebeat surveyed. But the counties tha

t do keep track suggest the number is significant, meaning there are likely thousands of Michiganders whose votes on the partisan section aren’t counted each election. (Votes in the other sections of the primary ballot — for nonpartisan candidates, proposals or millages — are unaffected by the mistake, and still get counted.)

Two years ago in Macomb County, for example, nearly 6,300 ballots — about 3.6% of the more than 175,000 people who voted in the county’s August primary — had a crossover vote, officials said.

Washtenaw County doesn’t explicitly track rejections due to crossover votes, but Votebeat’s analysis of vote data from the county suggest the total was close to 1,400 votes in 2022, or roughly 1.5% of the 87,526 votes cast there. Even if that relatively low percentage was consistent statewide, Washtenaw County Clerk Lawrence Kestenbaum said, it would still be thousands of votes across Michigan being excluded from the count.

The rate of crossover voting is a significant improvement over the “punch card days,” Kestenbaum said, when “something like 5% to 15% of primary ballots would not have partisan votes counted.” Punch-card ballots, which were largely phased out across the state by the early 2000s, didn’t enable voters to catch their mistakes in the way today’s electronic tabulators do.

That’s why the problem primarily affects absentee voters today, clerks say. If an in-person voter were to select candidates from different parties, the tabulator would flag the error, giving the voter the chance to correct the problem by spoiling their original ballot and filling out a new one.

Absentee voters don’t get that chance and will likely never be aware of the issue.

When election workers insert an absentee ballot with a crossover vote into a tabulator, “the tabulator will still beep,” said Meredith Place, Kalamazoo County Clerk. “But the inspector then has to select the button to cast the ballot anyway. They can’t fix the crossover vote, and the whole partisan section isn’t counted.”

In Michigan, more than 1.5 million people have requested absentee ballots ahead of Tuesday’s election, according to Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson’s office, exceeding the number requested in the same time period in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s not that voters aren’t given instructions on how to mark their ballots correctly, clerks say. Those who vote in person, either early or on Election Day, will get instructions from poll workers to stay within a single party column. There are also instructions printed on the top of ballots that tell voters to choose only one party. Many polling places will also have signage to further warn voters.

With mail ballots, there is an included instruction sheet that tells voters in capital letters: “YOU MAY VOTE IN ONE PARTY SECTION ONLY; YOU CANNOT ‘SPLIT YOUR TICKET.’ IF YOU VOTE IN MORE THAN ONE PARTY SECTION, YOUR PARTISAN BALLOT WILL BE REJECTED.”

But still, there are enough places for confusion that many voters miss the messaging altogether.

For one thing, the August ballot is not like the others. In February’s presidential primary, Michigan has a closed primary where voters have to request a specific party’s ballot, so there’s no risk of a crossover vote. In November’s general election, voters can vote straight-ticket or go back and forth as they please for each office.

But August — technically considered an open primary, because voters don’t have to declare a party — is ripe for problems, because voters may not be alert to the risk, especially if they’ve voted before and expect the August ballot to be like the others.

“If we did the regular primary the way we do the presidential, this problem wouldn’t exist at all,” Kestenbaum said.

Another concern comes from the design of the ballot itself, which has a number of flaws, according to Whitney Quesenbery, director of the nonprofit Center for Civic Design, which helps ensure best practices for ballots across the country.

Among the issues Quesenbery flagged: The text on the ballot itself is small. The separate instruction sheet that comes with the mail ballot has language that’s set by state law but is potentially confusing, and the important information on potential pitfalls comes after information on how to fill in a bubble, which could lead voters to ignore it altogether. The columns for separate parties don’t have a lot of visual space between them.

“This was all written into law by lawyers, not by the people who have to explain to people how things work,” Quesenbery said. “They don’t give enough attention to accurately explaining a complex system.”

Largely, clerks say they’re doing all the can to make sure voters are aware they can vote in only one column. Beyond that, there’s a level of what Hundley called “personal responsibility by voters” to make sure they read instructions.

But some clerks say they’d consider a change because, as Hundley also said, an election administrator’s goal is to make sure “the will of the people is accurately reflected.”

Any significant changes would require changing state law. Legislators aren’t really talking about addressing potential August primary confusion, said Rep. Penelope Tsernoglou, a Democrat from East Lansing, because few people have brought it to their attention.

The open primary creates a complication with crossover voting, but it helps to eliminate a reason that might discourage people from voting at all, because they don’t have to declare a party, Tsernoglou said. While she described herself as a fan of the open primary system, she said she’s “always open” to proposals to try to address concerns people have about voting.

Before making any major moves, she said she would want more information on the scope of the problem. In the meantime, she said she thought more voter education might help.

“If people are really struggling with this, I’d want to look at it and consider what we can do,” Tsernoglou said. “I want to do all we can to make voting fair, accessible and easy for everyone.”

Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org.