Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Michigan’s free newsletter here.

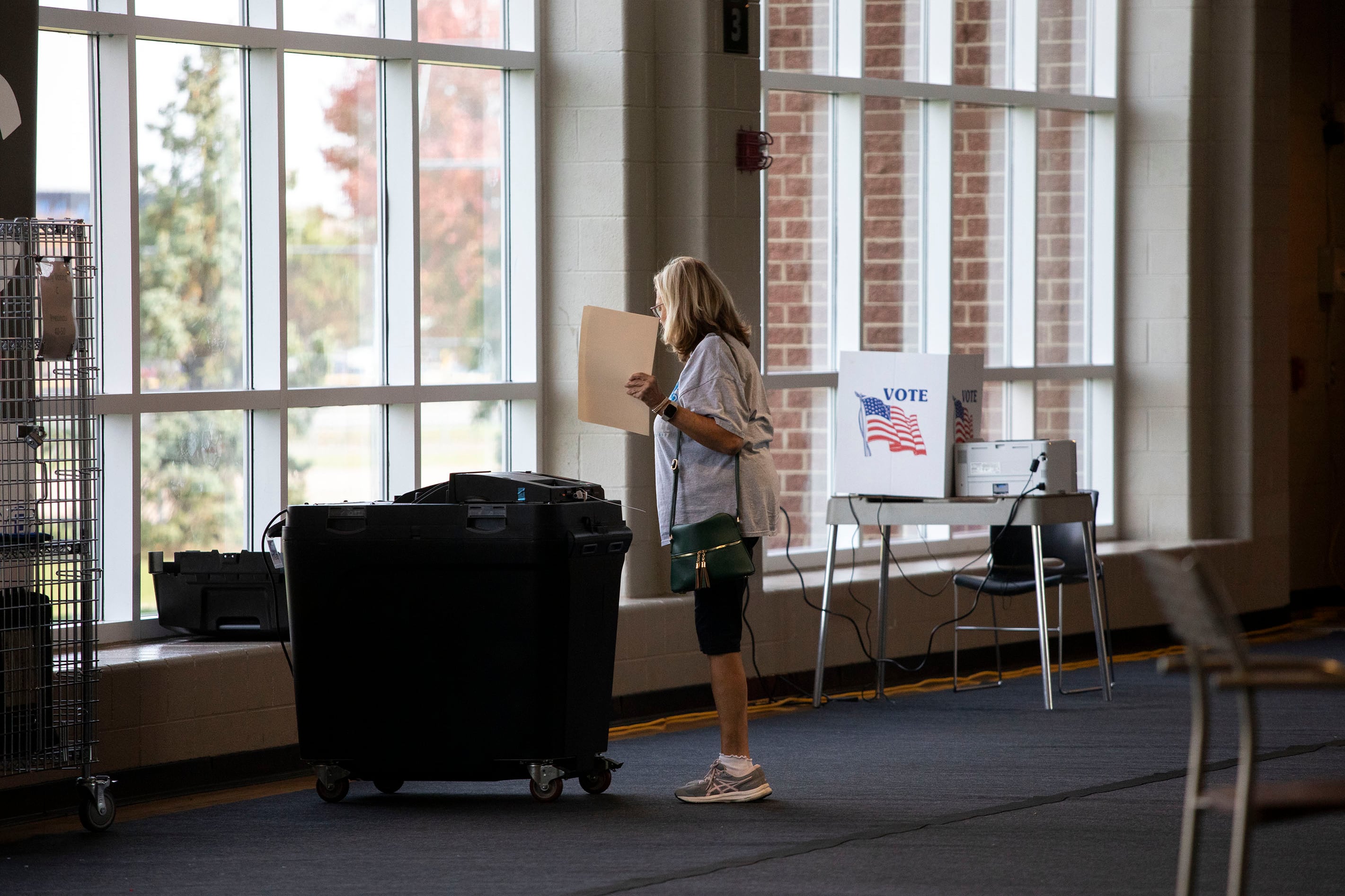

This Election Day, people around the country will be looking closely at the tight contest in Michigan to see who’s showing up to vote, how the vote counting proceeds, and what the results will show.

That includes bad actors, who will be seeking to profit in some way — maybe politically — by spreading inaccurate information as if it’s fact.

It can be easy to fall prey to mis- and disinformation, so we’re sharing information that can help debunk claims about Michigan before they can even be made.

Here’s what you need to know about Michigan’s elections to make sure you don’t get caught up in lies:

How do we know Michigan voters aren’t casting multiple ballots?

There are a lot of checks in place to ensure that each voter casts only one ballot.

Michigan uses something called the Qualified Voter File, which notes which voters have requested absentee ballots, who returned them, who voted early and so on. It’s the record of who’s allowed to vote, who has voted, and who hasn’t.

When someone who has already voted — either early in person or with an absentee ballot — checks in at their polling place to try to vote again, the QVF will inform poll workers that the person has already cast their ballot and cannot get a new one.

Double voting is extremely rare, but there are four voters who allegedly cast two ballots in the August primary election — one by mail and one in person. The double votes were quickly detected and they are now facing felony charges that could put them in prison for years if they’re found guilty.

Can poll challengers cause chaos at counting centers again?

Poll challengers in Michigan have a lot of power. They’re separate from poll workers or watchers, and they can challenge a voter’s eligibility or how officials are doing their jobs. They gained notoriety in 2020 when some challengers were denied entry at Detroit’s vote counting center (because there were already enough of them inside to reach the limit), and people gathered outside began to demand that the count be stopped.

They’re an important part of ensuring the transparency of Michigan’s elections, though. Any registered Michigan voter can be a challenger, but they must be credentialed by specific approved organizations. Clerks try to split challengers evenly between parties when possible.

Specific training is not required, but those offering credentials are encouraged to make sure challengers understand the rules so that they can “make informed challenges without disrupting or delaying election-related activities,” the 2024 guide says.

There are new rules in place to prevent such disruptions from happening again, with the end goal of getting counting done faster and more efficiently. Challengers have to make specific challenges, and they cannot make repeated failed challenges or blanket challenges without risking being removed from the facility.

Challengers cannot talk to or otherwise interact with voters — in fact, they can talk only to a dedicated challenger liaison. They can’t make audio or video recordings. And clerks have the right to limit the number of challengers.

Can homeless people vote in Michigan?

Yes! And it’s why you might see a lot of people whose voting records show them registered to a park, a street corner, or a church.

Homeless voters need to establish residency in some way, but like any Michigan voter, they can sign an affidavit in lieu of showing a photo ID.

A letters from a shelter or a group that works with the voter are acceptable, as long as it has their name and confirms that they live in Michigan.

Like any other voter in Michigan, voters without permanent addresses can register and vote on Election Day.

Is there a problem with Dominion voting machines in Michigan?

Only some of the machines have an issue, and it’s a problem with ease of use — not their security.

The glitch is occurring nationwide with Dominion’s voter assist terminals, which are the accessible machines designed to help voters who have disabilities. These are not tabulators; they are touchscreen ballot-marking devices that allow blind voters or others to use various assistive technologies to cast their ballots.

All polling places are legally required to have VATs, although not all of them use Dominion machines. Dominion VATs are used in 65 of Michigan’s 83 counties.

According to Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, the VATs nationwide have a programming error where if a voter uses the “straight ticket” voting option and then wants to vote across parties in some individual races (which is permitted in Michigan), they get an error.

It can be fixed by simply selecting candidates one by one down the ballot.

VATs are a critical for disabled voters, but each one is used by only a few voters each election, Michigan clerks say. The problem is annoying for those voters, but it will not affect most others.

Why does it take so long for Michigan results to come in?

It’s entirely normal to not know the results of the election immediately after polls close. Clerks say accurately counting thousands of ballots — millions across the state! — takes time. And in a very tight race, it’s hard to project a winner based on statistical patterns.

The state has done a lot in recent years to try to speed up the process, but it’s not perfect. Clerks have the option to process absentee ballots — take them out of the envelope, verify the signatures, and put them into the tabulator, but NOT count them — before Election Day, which many clerks, particularly in large cities, have opted to do.

We’ll likely have results from those ballots soon after polls close on Tuesday. But ballots that arrive on Election Day can take a while longer. There are also some potential bottlenecks in getting vote totals from precincts to clerks. Counties that use Hart machines, like Oakland County, can use modems — connected to secure cellular networks, not the internet — to transmit results quickly. In other places, results must be shared through a closed computer network (again, not on the internet) and then verified with data from portable data storage devices that are driven in from the precincts. That can take a long time.

It’s possible that Macomb County in particular could have slow results this year. Warren, its largest city and the third most populous in the state, has chosen to not pre-process ballots.

Does Michigan have more voters than people eligible to vote?

No. The claim has been debunked extensively by the state as well as independent experts.

Michigan has 7.2 million active voters and 7.9 million residents over the age of 18. (We have a high registration rate in part because anyone who gets a driver’s license is automatically registered to vote.)

In total, Michigan has 8.4 million registered voters on the rolls, but that number is misleading. About 1.2 million of those are records of inactive voters that cannot be cleared because of federal rules about cleaning voting rolls. They are labeled inactive because they haven’t voted in the past two federal elections or responded to election mail.

When people move and don’t cancel their registration in Michigan, they can appear on that list as an inactive voter for years. Others on that list may be dead, although there’s no evidence that dead voters are somehow voting.

Active voters and registered voters are not the same thing.

Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org.