Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Michigan’s free newsletter here.

A set of bills that would expand voting rights for non-English speakers and voters with disabilities is moving closer to becoming state law after the House elections committee voted Tuesday to advance the bills championed by Democrats and Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson.

In a vote along party lines, the committee passed four bills that make up the proposed Michigan Voting Rights Act. Next, the bills will go before the entire House for a vote. They were approved by the Senate back in September after spending nearly a year in that chamber’s committee.

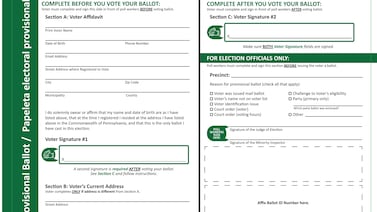

The bills aim to expand ballot access by providing ballots in more languages, create a voting data clearinghouse, codify protections for voters who may need help casting their ballot, and broadly aim to prevent voting suppression.

If signed into law, they would be yet another consequential change in Michigan’s election laws, which have seen massive changes in the past few years as voters have approved constitutional amendments to expand voting rights through same-day registration and early in-person voting.

Lawmakers appeared to resolve one of the biggest concerns about the bills: who would actually pay for the significant costs the legislation would impose. Deputy Secretary of State Aghogho Edevbie said recent House amendments to the bill would place much of the financial burden — about $15 million, he estimated — on the Department of State rather than local governments.

But the costs were just one area of concern from clerks and opponents to the bills. They fear that in an attempt to fill in gaps left by the recently weakened national Voting Rights Act, the state risks placing a heavy burden on local clerks to meet ambitious voting requirements.

The bill package has been a legislative priority for Benson and other Democrats. But if it does not pass this session, it is unlikely to become law; Democrats lost control of the House in the November election. Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has not publicly weighed in on the bills, but she has supported other Democratic expansions of voting rights.

Clerks worry about liability, challenges for early voting

The bills would expand language support, including translated ballots, to a wide variety of additional communities not covered by the federal Voting Rights Act. That could include Arabic, which is not covered by the VRA.

In Detroit, it’s possible the city could add more than half a dozen languages to the translations it provides. In Coldwater, a Branch County community with a population around 14,000, it would mean providing support in at least three languages, Delta Township Clerk Mary Clark told the committee.

Those requirements had previously created a major concern over the costs of the new laws. One of the biggest estimated expenses originally was in providing extensive printed election materials translated into multiple languages: around 230 separate election documents, including the manual provided to clerks on how to administer elections. Recent revisions to the bill reduced the number of documents that need to be translated to only the ballots and 22 pages of documents that voters might use, Edevbie said.

In addition to other changes, the bills would also codify curbside voting for those who can’t physically enter a polling place, and allow people to provide food and other things to voters inside or outside a polling place. The MVRA would also create a data clearinghouse within at least one of the state’s public universities to allow broader access to voting data.

Rep. Rachelle Smit, a Republican from Martin and the minority vice chair of the elections committee, asked Benson why the MVRA went so far beyond its federal counterpart. Benson responded by noting the VRA has been rolled back in several ways by courts.

Several local clerks told Votebeat in October that they supported the changes from the MVRA in theory, but that the scope of the bills and the potential penalties made them untenable at best.

That was the sentiment shared by Lansing City Clerk Chris Swope, who spoke to the House committee Tuesday on the behalf of the Michigan Association of Municipal Clerks.

“If you had told me a year ago that I would ever testify in opposition to anything called a voting rights bill, I would have laughed in your face,” Swope told the committee. “It’s a little bit sad to me that we are in this position.”

He flagged concerns about penalties against communities that fail to follow the legislation as proposed, particularly for reasons related to simple human error rather than a malicious attempt to suppress voters.

The bills allow voters to sue municipalities for alleged violations of the law, including diluting the vote through redistricting or moving a polling place to a new location deemed inaccessible. If that lawsuit is not resolved independently, the state or even the courts could instead make changes, such as drawing new districts or selecting new polling places.

Such “preclearance” requirements were central to the federal Voting Rights Act in areas with a history of discriminatory voting practices, until the U.S. Supreme Court dismantled those protections in its 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision.

Swope also expressed concern about how the bill package would enable judges to allow remedies that are currently illegal under Michigan law, such as ranked choice voting. Ranked choice voting has been approved by voters in several communities but cannot be implemented without a change in state law.

“You could end up with a situation where a community that wanted to do ranked choice voting then gets sued, and the court orders ranked choice voting,” he said. “Yet the community is still looked upon as having violated the voting rights of their constituents when it’s something they were already trying to do but weren’t allowed by state law.”

Oakland County Clerk Lisa Brown told the committee that if the state codified curbside voting, it would create a liability for the county, and that she would have to stop taking the lead on centralized early voting for her communities.

That would force each city and township to run its own early voting rather than relying on the county to run shared early vote centers, which can be an expensive and time-consuming process immediately before Election Day.

“Our early voting sites were not made to accommodate curbside voting,” said Brown, who runs early voting for the majority of her county, covering more than 900,000 voters. “It was really hard to find enough locations that we could utilize for nine days — or really, 11 days, because a day for setup and a day to take it all down.”

She also criticized the “unfunded mandate” of requiring two additional poll workers per location to help with curbside voting. Without funding, she said she feared it would have a “chilling effect” on clerks across the state, discouraging interested people away from the job because of the work required.

Edevbie countered that curbside voting is already required by Michigan’s election manual, so these legal changes should not impose a significant additional burden. The manual is not law, but rather a lengthy set of instructions provided by the secretary of state’s office to local election officials.

Benson: Bills make voting rights ‘real’ for residents

In addition to Benson, ACLU of Michigan, Detroit Disability Power, and others expressed support for the MVRA. They all argued that the changes proposed would expand voting rights at a critical time.

Benson said that recent changes to Michigan voting law helped the state reach the number two ranking on the Elections Performance Index, which is run by the MIT Election Data and Science Lab.

“What the Michigan Votings Rights Act really is about is making sure that constitutional right is real, just in the way that you’ve passed legislation to make other constitutional rights ... real for our citizens,” she told the committee. “This is, in my view, the additional piece that needs to happen, the additional legislation that is needed to make those constitutional rights real for our residents.”

The party will continue to hold both chambers until the end of the year, so Democrats have been trying to push several pieces of voting legislation through during the lame duck session.

Whitmer announced Tuesday, for instance, that she signed bills to make it illegal to have a firearm at polling places or counting boards.

Other pieces of voting legislation, including those on the national popular vote and signature collection for petitions, are also in motion.

The national popular vote effort seeks to add Michigan to an emerging interstate compact that could someday lead to committing these states’ presidential electors to the winner of the national popular vote.

Signature collection laws, meanwhile, seek to provide new requirements to help eliminate some of the problems that have popped up in recent years due to faulty signatures. These have kept candidates off the ballot in a number of races across the state.

The end of the legislative session is scheduled for Dec. 19.

Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org.