Good-government advocates and voting experts say Pennsylvania should change a recount law that was weaponized by activists and delayed the state’s certification by several weeks.

A Votebeat and Spotlight PA review of historical legislative records and news articles found that the 1927 provision has not been substantially updated in the near-century since its passage, and was designed to combat a type of fraud now easily detected by modern improvements to election administration.

The recount petition fee, for example, has never been updated from the $50 amount set in 1927. Adjusted for inflation, the modern equivalent is $860.

By design, the authors of the law specifically didn’t require citizens submitting recount petitions to include proof of fraud. That means almost none of the petitions submitted this year offered actual evidence of malfeasance.

“Having an outlet for a citizen who sees something is important,” Commissioner Josh Maxwell, chair of the Chester County elections board, said. Instead, “there was no fraudulent behavior and [the statute is] being abused and used possibly to delay the certification of elections.”

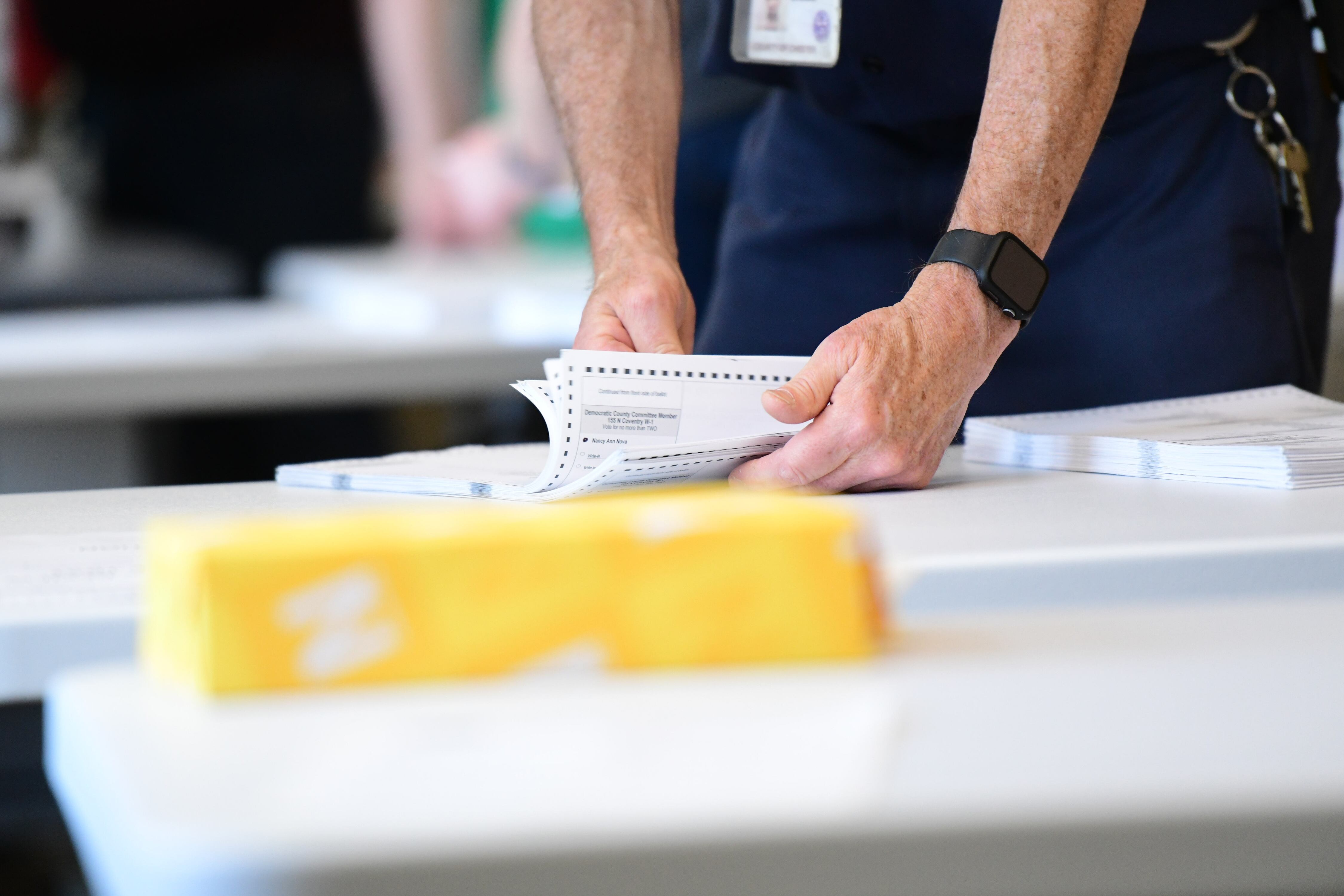

Roughly 150 petitions were filed across the state in November, most targeting the gubernatorial and U.S. Senate races. The petitions held up certification in several counties as judges considered them and, in the counties where recounts moved forward, election administrators fed the ballots back through high-speed scanners. None of the outcomes were altered by the recounts, which found almost no errors.

This year, “I think the scope and the motivations [behind the recount petitions] are pretty novel,” said Forrest Lehman, elections director in Lycoming County. He noted that Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein did use the provision in a “scattered” way, relying as well on other parts of Pennsylvania election law. This year, he said, “you had people filing dozens” of petitions.

Adam Bonin is a Philadelphia-based attorney who regularly works with Democratic candidates and said he has used the statute in local races, such as school board or township supervisor races, when the margin is close and a recount may be justified.

The low fee of $50, originally “meant to be cost-prohibitive,” has now made it too easy to file such requests due to inflation, Bonin suggested, describing the amount as now equivalent to “a rounding error.”

Lehman and Bonin said the statute should at least be adjusted for inflation.

But Elizabeth Grossman, a senior regulatory counsel at Informing Democracy, a nonprofit focused on the vote-counting process, has been researching the law’s origin and said simply upping the cost may not be the right solution. While cost provisions and evidence standards might lessen the number of petitions, motivated parties who refuse to accept the results will climb whatever barriers are placed before them. Instead, she said, the state should consider whether the 1927 provision is still needed at all.

“I think this is more about ‘what is this for,’” she said. “If the purpose is to check if there is an error, we don’t need it. This is an old bill. We have recounts when the margin is slim, and we have audits in Pennsylvania.”

Provision dates back to 1927

The provision was championed by the newly elected Republican Gov. John Fisher as part of a package of election reform proposals Fisher had offered during his 1926 campaign. It had been a cause championed by his predecessor, Gov. Gifford Pinchot, also a Republican.

Fisher and Pinchot were attempting to push back against what they saw as the corruption of elections by machine politics, which, Pinchot said in a 1926 address to the state Legislature, was on display when attorneys in Philadelphia sought to block the opening of ballot boxes in the 1925 election. Those later showed “undisputed evidence of fraud,” he said.

According to coverage at the time from The Philadelphia Inquirer, “glaring debauchery” was committed against Benjamin H. Renshaw, who’d received zero votes out of more than 20,000 that were cast in his race for judge. Renshaw’s campaign petitioned for recounts in 25 precincts, submitting sworn statements from voters who had voted for him or who said they saw ballot boxes being stuffed. He was aided by the Committee of Seventy, an influential Philadelphia-based nonpartisan nonprofit that advocates for good government measures aimed at improving democracy, such as informing voters and combating corruption.

In one incident, a judge of elections told a watcher for Renshaw’s campaign that he would only credit Renshaw with 50 votes — and the watcher was told to “take that or nothing.”

But despite what many considered extensive evidence of election malfeasance, not all the petitions were granted. As a result, Pinchot formed a “committee of 76” prominent men from around the state to consider necessary election reforms. According to newspaper coverage at the time, one of the committee’s recommendations was to take away judicial discretion when it came to recount petitions.

Fisher’s bill did that, mandating that the ballot box be opened if three voters in a precinct posted $50 and submitted a petition stating it was their “belief” that fraud had occurred in a race. The money would only be returned if fraud was found. The law also said, as it still does today, that the petitioners did not have to provide evidence of their claims. The logic behind this was articulated in a March 1927 editorial in The Inquirer.

“Since whatever evidence of fraud or error is locked up in the box, the petitioners are not required to prove corruption in advance,” the editorial read.

But that’s no longer how elections operate, said Al Schmidt, current president of the Committee of Seventy.

“No doubt Philly had a problem with voter fraud a long time ago, as did every other major American city, but there are safeguards now that exist that didn’t then,” said Schmidt, pointing to modern updates such as voter ID requirements for mailed ballots and banning party committee members from collecting ballots.

‘Unsupported’ petitions cause delay, spark calls for change

The Department of State said there was a “significant increase” in the number of counties receiving “unsupported” petitions filed this year. In 2016, Stein’s petitions targeted 15 counties and were heavily concentrated in Allegheny and Philadelphia, according to the Department of State. The petitions this year were spread out across at least 27 counties, according to a spokesperson for the state’s court system.

The agency told counties they could delay their certification past the statutory Nov. 28 deadline if they received valid petitions. Many did, leading to the latest date for full state certification, Dec. 22, in at least the past three years.

Some petitions are still pending in Bucks County, but most were dismissed. Judges were particularly incensed by petitions filed by judges of elections, who filed recount petitions in their own jurisdictions despite previously certifying the results.

One Republican judge on the Court of Common Pleas, Jeffrey Sommer of Chester County, released a scathing opinion castigating the petitioners for embarking on what he called a “fishing expedition.”

Some judges, relying upon a separate part of election code which says if voters are going to use the 1927 provision they have to have at least some evidence or submit petitions in every voting district, dismissed petitions for lacking evidence.

Others, confounded by both the vagueness of the law and apparent contradictions within state statutes, urged the Legislature to amend the 1927 provision.

“A sustained failure to address this deficiency will continue to burden the courts, elections bureaus, elections boards, county executive branches and the voting public by allowing manufactured challenges without a scintilla of evidentiary support to any and possibly all election certification processes in future elections,” Harry Judge Smail Jr., a Republican judge in Westmoreland County, wrote.

Election law experts say the lack of clarity around an evidentiary requirement should be addressed by the Legislature.

Lycoming’s Lehman said the Legislature should consider an evidentiary standard, a sentiment echoed by state Sen. Ryan Aument (R., Lancaster), whose race was the subject of such petitions, and by Schmidt, who was targeted by former president Donald Trump after speaking out against false claims of voter fraud in Philadelphia while serving as a commissioner there.

“I think it is a matter of having to put forward some evidence that an impartial juror could consider when considering where to examine that election,” said Schmidt. “That mechanism is in the code for some reason and the solution isn’t to get rid of it because some people are abusing it; it is to require evidence. The great thing is that the courts can be a ‘put-up-or-shut-up’ moment when it comes to election lies.”

The delayed certification may not have had reverberating impacts in 2022, but Grossman said she is worried about the potential for chaos in a presidential election year when the state must submit certified results for the Electoral College in early December. Schmidt, as well, said he is worried about future elections without legislative intervention.

“You could say, ‘What is the harm of having them certify a few days later,’” Schmidt said. “2020 showed they are trying to prevent certification. Just because someone isn’t trying what they did in 2020 doesn’t mean they aren’t testing vulnerabilities to the system.”

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.