Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

A federal appeals court decision upholding Pennsylvania’s rules for voting by mail could mean that tens of thousands of ballots are rejected in this year’s election because they lack a date or are misdated. But the full impact of the ruling is still up in the air while the parties who brought the case decide whether to appeal.

A panel of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 2-1 Wednesday that a Pennsylvania law requiring mail voters to handwrite a date on the return envelope did not violate a provision of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that’s meant to protect voters from being denied the right to register to vote.

The decision could have broad implications: If plaintiffs appeal to the Supreme Court and justices uphold it, it could become precedent for the entire country, rather than just the jurisdictions in the 3rd Circuit. Such a ruling could limit how the Civil Rights Act applies to requirements for casting a ballot.

And some conservative justices already hinted in an earlier ruling that they’re skeptical of the argument that the date requirement violates the Act. When the court nullified a previous opinion from the 3rd Circuit that ruled such ballots should be counted, three of the court’s conservatives wrote that the lower court’s opinion was “likely wrong.”

The plaintiffs will now need to make a choice about whether it is worth pushing this case forward, or containing the decision to the 3rd Circuit, said Derek Muller, an election law professor at Notre Dame Law School.

“I think there’s a lot of challenges raising it with the Supreme Court if you are the plaintiffs,” he said. “You’ve already got three justices who sketched out a preliminary position against your position, so I just think it’s an uphill battle to go to the court and make that claim now.”

Andy Hoover, a spokesperson for the ACLU of Pennsylvania, which represented the plaintiffs, said, “We are analyzing the ruling and have not made a decision about next steps.”

The Department of State, which was a defendant in the case but took the view that the ballots should not be rejected, said in a statement that it was “reviewing potential next steps” and highlighted recent changes it made to the return envelopes that it hopes will reduce the number of ballots rejected this year.

Even if it is appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court — given where we are in the court’s current term — Muller thinks any decision would be unlikely to come before 2025.

“My guess is this rule will be in place for 2024.”

There may be other action in the courts in the meantime.

Adam Bonin, a Philadelphia-based attorney who regularly works with Democratic candidates, is currently representing a township supervisor candidate in a case tangentially related to the 3rd Circuit appeal.

“I think the majority got it wrong here,” said Bonin, who was also involved in a 2021 case from Lehigh County on the same issue. “This was a remedial statute intended to remove all sorts of barriers to the right to vote. I thought that Congress was very clear that this goes to all the steps” that involve ensuring a vote is counted.

The three-judge panel’s ruling can still be appealed to the full 3rd Circuit by April 10.

For their part, Republicans are embracing the decision as a victory.

“The Court ruling is a gigantic win for Pennsylvania, the nation, and election integrity,” said Chairman Lawrence Tabas of the Pennsylvania GOP, which was one of the intervening defendants in the case.

Wednesday’s ruling, from a three judge panel of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, centered on whether the date requirement under Pennsylvania election law violated a part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act known as the “materiality provision.”

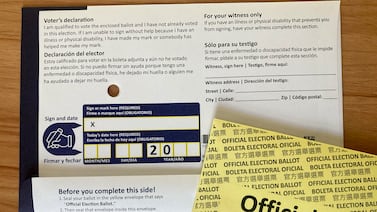

That provision says a person cannot be denied the right to vote because of “an error or omission on any record or paper relating to any application, registration, or other act requisite to voting, if such error or omission is not material in determining whether such individual is qualified under State law to vote.”

The majority on the panel ruled that the provision only applies when the state is determining who may vote.

“In other words, its role stops at the door of the voting place,” Judge Thomas Ambro, an appointee of former Democratic President Bill Clinton, wrote for the majority. “The Provision does not apply to rules, like the date requirement, that govern how a qualified voter must cast his ballot for it to be counted.”

Mike Lee, executive director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania, said in a statement that if the decision stands, thousands of Pennsylvanians could lose their vote over a “meaningless paperwork error.”

“The ballots in question in this case come from voters who are eligible and who met the submission deadline,” Lee said. “In passing the Civil Rights Act, Congress put a guardrail in place to be sure that states don’t erect unnecessary barriers that disenfranchise voters. It’s unfortunate that the court failed to recognize that principle. Voters lose as a result of this ruling.”

Ruling distinguishes registration barriers from voting rules

Unlike the last time this question was before the 3rd Circuit, the court split on the issue, voting 2-1 against the plaintiffs.

Ambro, along with Judge Cindy Chung — an appointee of Democratic President Joe Biden — took the view that the materiality provision is limited to documents related to a voter registering to vote, which would “restrict who may vote.”

“It does not preempt state requirements on how qualified voters may cast a valid ballot, regardless what (if any) purpose those rules serve,” the opinion read.

Much of the decision came down to whether the provision deals only with documents related to registering to vote, or whether its reference to “other acts requisite to voting” applies to other documents voters may encounter when trying to cast a ballot. Ambro and Chung argued that when the materiality provision is read in context with the sentences around it, along with the discussion among legislators who wrote it, it was clear that it related only to registration documents.

They also argued that rejecting undated or improperly dated ballots did not take away the voter’s ability to vote and that states had the freedom to make rules concerning how votes are to be cast, such as rejecting mail ballots that have identifiable markings on the secrecy envelope.

“A voter who fails to abide by state rules prescribing how to make a vote effective is not “den[ied] the right . . . to vote” when his ballot is not counted,” Ambro wrote. “If state law provides that ballots completed in different colored inks, or secrecy envelopes containing improper markings, or envelopes missing a date, must be discounted, that is a legislative choice that federal courts might review if there is unequal application, but they have no power to review under the Materiality Provision.”

Judge Patty Schwartz — an appointee of former Democratic President Barack Obama — disagreed, noting that the date on the mail ballot return envelope is in relation to a declaration that states “I hereby declare that I am qualified to vote in this election,” which makes it fall under the provision.

She also pointed out that the 1964 Civil Rights Act defines “voting” as “all action necessary to make a vote effective including, but not limited to, registration or other action required by State law prerequisite to voting, casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted and included in the appropriate totals of votes cast.”

When this section is read in conjunction with the materiality provision, she argued, the dating requirement becomes subject to that provision.

How we got here

Wednesday’s decision came as part of an appeal of a November 2023 ruling from U.S. District Judge Susan Baxter in the Western District of Pennsylvania.

Shortly after the 2023 election, she ruled that the whether the ballot envelope had a date was “immaterial” to a voter’s eligibility, and that ballots should not be rejected over what is essentially a technicality.

“There are many reasons to date a document,” Baxter wrote at the time, adding, “Dates may also be wholly irrelevant, as in this case. The requirement at issue here is irrelevant in determining when the voter signed their declaration.”Her ruling was just part of a string of disputes over whether to count undated or incorrectly dated mail ballots that have been before the courts since the state’s no-excuse mail voting law, Act 77, passed in 2019.

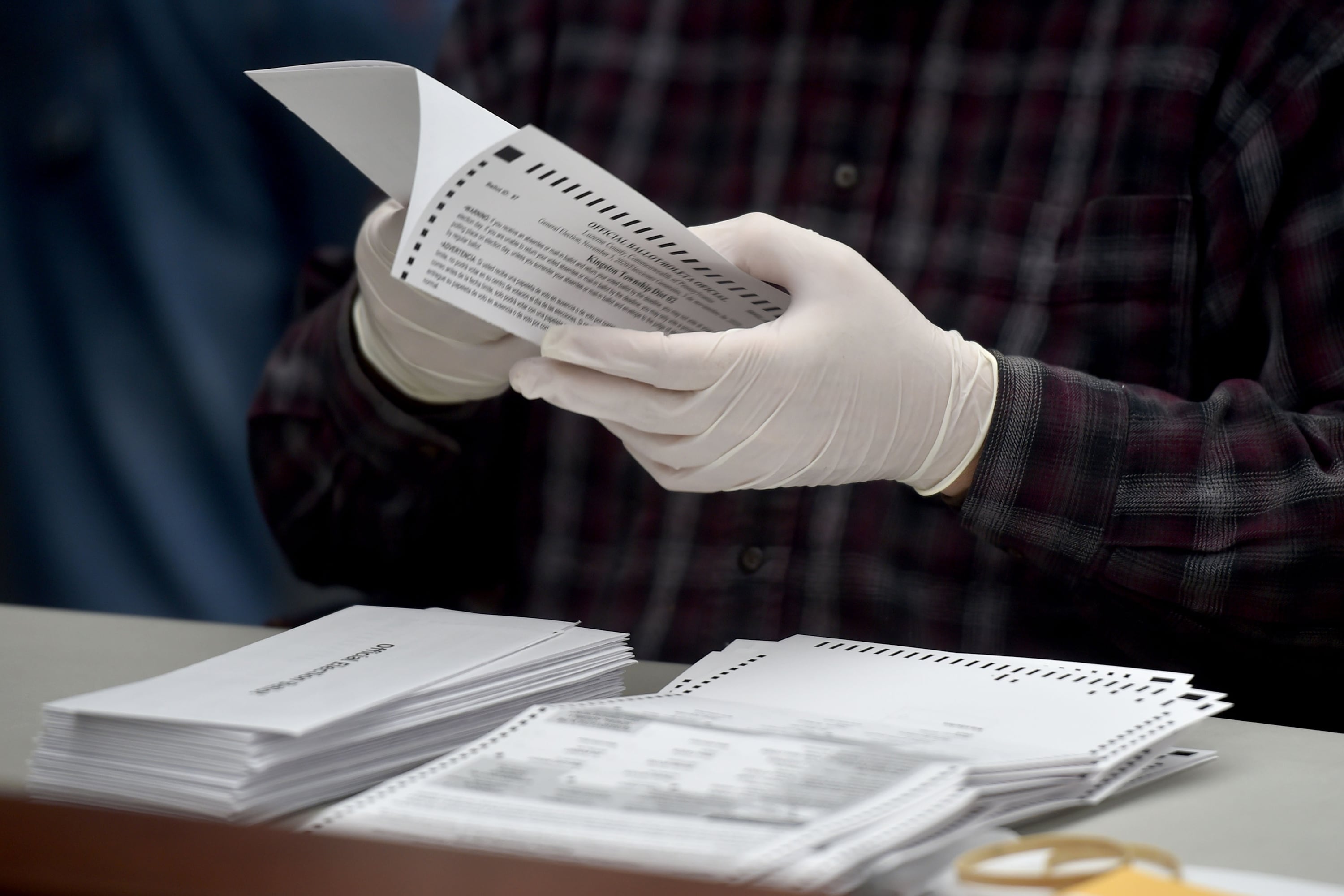

That law required that voters sign and date the outer return envelope.

A 2021 case out of Lehigh County challenged the provision, citing the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s materiality provision.

In 2022, a separate three-judge panel of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously agreed in the Lehigh case that the date issue was immaterial, but the U.S. Supreme Court nullified the ruling later that year, after one of the candidates in the race in question conceded.

That left the question up in the air again ahead of the 2022 midterm election, until the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled on Nov. 1 that counties should not count the ballots if they were missing a date. The court defined an incorrectly dated ballot as one that fell outside of the time range for acceptable ballots, Sept. 19 through Nov. 8, 2022, the first day mail ballots were sent out through the day of the election.

In practice, this has often led to counties rejecting ballots that they know were cast in the correct time period.

Roughly 8,000 ballots were rejected during the 2022 midterm election for lacking a proper date or signature on the outer return envelope, according to the Pennsylvania Department of State.

A Votebeat and Spotlight PA analysis of data from three counties in 2022 — Philadelphia, Allegheny, and Erie — found voters submitting the flawed ballots were more likely to come from communities with higher than average non-white populations compared with the overall voting population in the county.The department began being able to track rejections specifically for dating issues in 2023, and said in last November’s election the issue accounted for roughly 2,500 rejections.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.