Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

When Northampton County voters cast their ballots in an election last November, it became clear to them very quickly that something was wrong.

On the printed records that are meant to show them how they voted, the votes they cast in one judge’s election were appearing under another judge’s name.

“It’s a joke,” one frustrated voter told Lehigh Valley News on Election Day. “We don’t even have faith in the electoral system, then this happens?”

The mixup — the result of an error in programming voting machines — didn’t result in any votes being counted incorrectly, because the machines don’t rely on the text of that printed record to tabulate results. Nonetheless, it was the kind of error that should have been caught and demonstrates the importance of putting voting machines through robust pre-election testing. And in Northampton County’s case, it was part of a larger pattern of testing flaws that went beyond an undetected programming error.

A Votebeat and Spotlight PA investigation into the county’s preparation for last November’s election found that its testing documentation was incomplete, inconsistent, and in more than 150 cases missing entirely, making it difficult to prove that it tested its machines correctly.

“Obviously, it’s not the way it is supposed to happen,” said Kevin Skoglund, president and chief technologist of the Pennsylvania-based Citizens for Better Elections who has studied the model of machine Northampton County uses. “Imagine if you took your car in to get your brakes checked, and then something went wrong and you went back and they couldn’t prove what they’d done.”

The county’s lapses don’t point to any malfunction or malfeasance with the voting machines, and the Votebeat and Spotlight PA review didn’t find any. But even benign errors threaten to undermine voters’ confidence in election administration and feed conspiracy theories about fraud, as Northampton experienced last year. That’s partly why the state requires counties to document the testing of every machine they use ahead of each election.

In response to Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s findings, Northampton County has made efforts to correct its procedures. But its original lapses do raise questions about how faithfully counties around the state are following requirements for testing their machines and documenting what they’re doing. Some outside observers, including state legislators, are wondering whether a legislative fix is needed.

State Sen. Jarrett Coleman, a Republican from neighboring Lehigh County who has been skeptical of Northampton’'s testing process, is working on such a bill. “Northampton County’s neglect to properly test election equipment and document it is abhorrent,” he said after seeing the Votebeat and Spotlight PA findings.

How pre-election machine testing is supposed to work

Before each election, counties are required by law, and directives from the Pennsylvania Department of State, to test the election equipment they will use to ensure it is working properly. This is known as “logic and accuracy” testing.

The testing looks for problems that could arise during voting or tabulation, such as machines being unable to read ballots, miscalibrated touch screens, and incorrect vote totals.

The testing is “intended to ensure that ballots, scanners, ballot-marking devices, and all components of a county’s certified voting system are properly configured and in good working order prior to being used in an election,” according to a Pennsylvania Department of State directive on machine testing.

Typically, a county or its vendor — representatives of the voting machine manufacturer — will first design and print a “test deck”: a set of mock ballots that simulate different combinations of votes that could be cast by voters.

For example, in a county commissioner’s race where voters can select two of three candidates, a test deck would include ballots that would account for the different combinations.

But before any of the test ballots are put through the tabulator, inspectors print out a “zero tape” from the tabulator machine. The zero tape — a strip of paper that’s like a receipt from a cash register — serves as proof that the machine doesn’t have any votes already recorded.

After the test ballots are run through the machine, inspectors print out another strip of paper, the results tape, which shows what the vote totals are for each candidate or question on the ballot. They then compare the ballots in the test deck and the results tape to ensure that the vote totals match.

The exact process can vary depending on the types of machines the counties use — some have voters make selections on a touch screen — but no matter what, the testing protocols are intended to ensure that a tabulating machine generates results that accurately reflect voters’ choices.

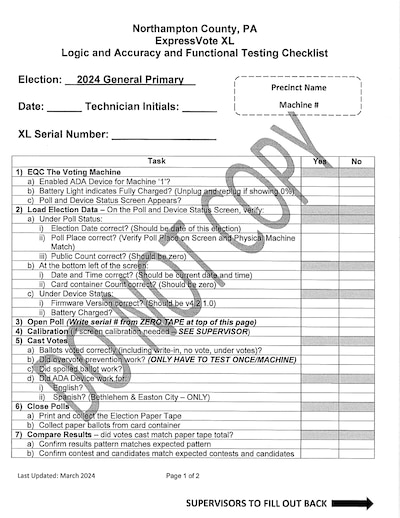

The inspector also reviews various functions on the machine and uses a checklist to record each step. This includes things such as whether the machine’s date and time are correct, if the machine can read the ballot without error, and if vote totals were cleared from the machine after the test deck is run through the tabulator, so that the machine is ready to use for the actual election.

The process is important not only because it helps ensure a smooth election and the state requires it, but also because it generates a paper trail — proof for county officials that they completed the testing and that the system worked.

“Hypothetically speaking, if there are people that are saying something is incorrect, we would obviously do a full investigation on the matter, and that starts with this paperwork,” said Karen Barsoum, election director for Chester County.

If a machine doesn’t go through the testing, she said, it’s not used at the polls, because there’s otherwise no way to show it was functioning properly.

How one voting machine error slipped through

Northampton’s voting machine, the ExpressVote XL, is an all-in-one “ballot marking device.” Voters insert a ballot card into the machine, make their selections on a touch screen, and the machine prints those selections onto the ballot card, in text form and in a barcode. The machine then reads the barcode to tabulate the results and stores the paper ballot card in an internal hopper, to be retained for post-election audits or recounts.

This means that for pre-election testing, inspectors handle the test deck differently. They replicate the votes shown on the test deck by entering the selections on the machine’s touch screen. The machine prints those votes onto a ballot card, displays them to the inspector, and then tabulates them internally.

In the November election that went wrong, two state judges were running in retention elections, where voters had to choose, with a yes or no vote, whether to keep them on the bench.

But in the run-up to that election, an employee of the county’s election machine vendor, Election Systems & Software, incorrectly programmed the machines in a way that produced an incorrect text record on the printed ballot card.

A voter wouldn’t notice the misprint unless they had split their votes, voting “yes” for one judge and “no” for the other. If a voter voted this way, they would see that the text on their printed ballot would display their “yes” or “no” vote under the opposite judge’s race than they had intended.

The error didn’t affect the way the machines recorded the election results. That’s because the ExpressVote XL uses the barcode on the ballot card — not the printed text — to tabulate voting results, and the barcodes were printed correctly, county and ES&S officials said.

The programming error went undetected during the test run in October, because Northampton did not check this specific scenario with its test deck — a ballot where a voter voted “yes” on one of the judges and “no” on the other one.

But the error was enough to create confusion on Election Day.

Additional problems Votebeat and Spotlight PA discovered

The county’s issues went further than simply not testing enough permutations. Records show a disorganized, incomplete process, with no evidence of machine inspectors’ work being double-checked for accuracy.

A Votebeat and Spotlight PA reporter spent nearly 14 hours over six days going through the county’s logic and accuracy testing documents from October 2023. The reporter also inspected a box of documents and spoke to an official from another county to compare the way records were maintained.

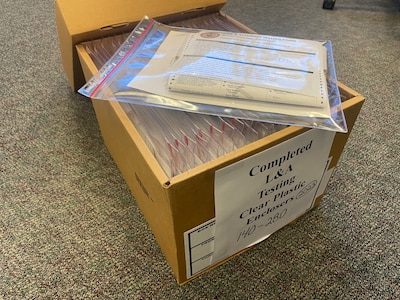

The Northampton documents — test decks, zero tapes, results tapes, checklists, and test ballots printed out from the ExpressVote XL — were stored in four file boxes. A reporter was allowed to access and make copies of the documents following a public records request.

What stood out immediately was a lack of organization. Northampton County Election Director Christopher Commini said that after the test was performed in October, bags containing each machine’s testing documents were dumped into the file boxes. This left them in no discernible order, and testing documents for a single machine were often split across multiple boxes.

Mixed in with these documents were also a zero tape and checklist from the 2023 primary, while many checklists had no date on them at all, raising questions about whether they were from the right election.

By contrast, in Chester County, Barsoum keeps her documentation neatly organized. Each machine’s test deck, tapes, checklist, and other documents are neatly folded and placed in clear, resealable envelopes and kept in file boxes indicating which election they are for. The sealing end of the envelopes are even staggered in the box, to keep the stacks orderly.

In Northampton, Commini downplayed the misfiled documents, noting that it was only two items out of four filing boxes and not indicative of a widespread issue, but he acknowledges the county’s organization is lacking.

“We recognize that in the past, there was no process to keep these documents in order,” he said. “We are aware now that we need to create a new filing process for this information, and we are going to take steps to do so.”

The checklists in Northampton’s boxes weren’t just misfiled. Large numbers of them were incomplete or inconsistent. More than 200 did not have the back filled out, which includes steps like removing mock ballots from the machine after testing. Some inspectors completed some questions that others skipped. And in some cases, the same inspector would fill out the same checklist differently for two precincts’ machines. None of the checklists had the line for supervisor’s initials filled out to indicate the inspector’s work had been checked.

(Story continues below graphic)

The testing was performed by a mix of county employees — some from outside the elections department — and ES&S employees, with ES&S providing the training. Commini said while there are supervisors from the elections office and ES&S overseeing the process, those employees did not examine the inspectors’ checklists to ensure they were complete.

The checklists also lacked serial numbers that would indicate which machine they were for, so in most cases they couldn’t be linked afterward to a particular machine or its zero and results tapes. Not a single checklist had a serial number written on it, according to Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s review.

One particular checklist that turned up in the review illustrates why this lapse is problematic. On that document, the inspector had checked “no” for all the questions related to that machine. That would indicate that the machine had several problems: that its tabulated results did not match the test deck, for instance, and that it did not prevent a voter from selecting more candidates than they were allowed to vote for.

Whether this was an error by the inspector in completing the checklist, or an indication that the machine was actually malfunctioning during testing, is difficult, if not impossible, to determine. Since the inspector did not record the machine’s serial number, or its assigned precinct, on the checklist, his answers cannot be checked against the corresponding tapes and test deck. This also means the paperwork can’t prove that a malfunctioning machine wasn’t deployed in the November election.

Commini said this inspector’s services “were not retained.”

Commini said that while the checklists are “useful” in indicating the functions of the machine were checked, they’re not critical in proving the machines were functioning properly.

He said it’s safe to assume, based on the election outcome, that a malfunctioning machine wasn’t put in service on Election Day.

“The public can be assured, because if a machine is not working, it is not deployed,” he added. “We can prove the machines worked properly by the information counted during the official canvass. This is when we go through the machines’ tapes and match them to the results we are reporting.”

Indeed, a machine’s proper functioning could be verified after the test with the zero tapes, results tapes, and test decks. But Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s review found that many of those documents were missing from the boxes.

In total, Votebeat and Spotlight PA identified over 150 documents or sets of documents — including checklists, zero and results tapes, and test decks — that were missing from the four boxes. Votebeat and Spotlight PA sent a list of these missing documents to county spokesperson Brittney Waylen and Commini, who initially said that there were other boxes in the warehouse that “may contain those items.”

But Waylen later said that after three trips to the Elections Warehouse, “Chris and his team could not find the boxes with the majority of the missing items.”

The county was able to find three of the documents that were missing.

Reforms in the works

In response to Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s review, the county made several changes to its process, and a reporter watched inspectors following that process during testing on April 8 for the upcoming primary. Each machine now has its own dedicated checklist with the precinct prewritten at the top.

The field for the machine serial number is on the front of the form, rather than the back, and testers are being specifically instructed to fill it out. The front also now has an arrow at the bottom to indicate that the back contains new sections to be filled out by a supervisor.

The county says it is also working on a better filing system.

“We definitely have to get better on a lot of the things we did,” Commini said. “These are major changes that need to be done.”

Other officials were troubled by Northampton’s problems and are interested in refining the logic and accuracy testing.

In a joint letter to the Senate State Government Committee, the Northampton County Democratic and Republican party chairs pointed out that the machines the county uses also had a calibration error in 2019, which was not caught by pre-election testing.

Matthew Munsey, chair of the Northampton County Democratic Party, said the testing that year was “awful” because the county used a feature built into the ExpressVote XL that automatically generated test ballots and ran them through the machine, rather than having test decks entered manually as the county does now.

He’s happy Commini made that switch, but still, the disorganization makes finding paperwork like looking for “a needle in a haystack,” and he has noticed over the years that the checklists were not being filed out, because as he was told: “There’s no need for them to be.”

“Sometimes people just put their initials down,” he said. “But it’s critical when you have a problem that you want to see what was done. … Failing to fill out the paperwork doesn’t show due diligence.”

Northampton’s lapses have also prompted state legislators to step in, seeking to make sure all counties are using best practices for testing.

Coleman, the Republican state senator representing neighboring Bucks and Lehigh counties and chair of the Senate Intergovernmental Operations Committee, said in an interview that he is working on a bill to tighten up the testing procedures.

“It shouldn’t take a [records request] and 14 hours of research to determine if your county tested equipment properly,” he said

He is working with the Department of State on a bill that would codify recent directives from the department on testing procedures. He said Pennsylvanians who buy gasoline can see right on the pump that the equipment was properly inspected, and he thinks voting equipment should be similar.

“The fact of the matter is it may have to be a state law for counties to follow the procedures,” he said. “This is insanity and at some point, the adults have to step in and say, ‘You didn’t listen to the Department of State, so the legislature has to step in and standardize the testing.’”

It’s unclear if other counties have the kinds of flaws and disorganization in their testing documentation that Northampton does. The Department of State said all counties provided certification that they had completed testing, although Coleman said he is still waiting to see the details of those certifications to know exactly how thoroughly counties are complying with the testing. But the granular documentation — test decks, results tapes — would only be available at the county level through records requests.

State Sen. Cris Dush, a Republican from Jefferson who chairs the Senate State Government Committee, said he will be co-sponsoring the legislation. Dush’s Democratic counterpart on the committee, Sen. Amanda Cappelletti, also said she was working with a Republican colleague to codify the Department of State’s directive, without mentioning Coleman’s bill directly.

Codifying the department’s recent directive would give the agency monitoring and enforcement authority, which would help prevent errors, Cappelletti said.

“These additional checks and balances will bolster Pennsylvanians’ confidence that our elections are being conducted appropriately,” she said.

The Department of State recently updated its directive on preelection machine testing to clarify what voting patterns must be used when testing to avoid problems like only testing “yes” “yes,” and “no” “no.” The department also offered new training sessions on how to perform the testing.

Jerry Feaser, a former Dauphin County election director with 10 years of experience, said during his tests a separate county election office employee would check that documentation was filled out properly. He thinks much of a county’s proficiency in the practice comes down to training.

Northampton’s 2023 documentation may have been more complete if a supervisor had signed off on each inspector’s work.

“This is one of these things where experience matters,” Feaser said.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.