Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Pennsylvania’s free newsletter here.

Update, July 19, 11:55 a.m.: This story was updated with additional comments from Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt to clarify his interview.

The Pennsylvania Department of State is hoping another change to mail ballot return envelopes will eliminate the chance of ballots being rejected this November because of voters failing to write in the year completely.

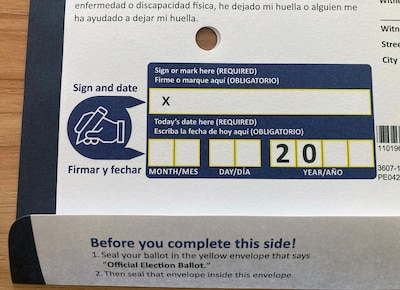

In a directive earlier this month, the Department of State told counties that they should now preprint ballot return envelopes with the full, four-digit year in the date field, leaving voters to fill in just the month and day alongside their signature.

“We conducted an analysis after this election of why ballots were rejected,” said Al Schmidt, secretary of the commonwealth. “We didn’t see a significant number of ballots missing the full year, but there were some, and every vote is precious in every election.”

It’s the second modification to the envelopes since the 2023 municipal elections, as state officials try to cut down on the number of ballots rejected for lacking a properly filled out date and resolve differing interpretations among counties on whether to count these ballots. The move will also eliminate a risk of lawsuits in November over whether incomplete-year ballots should be accepted or rejected.

Pennsylvania law requires that voters sign and date the outer return envelope of their mail ballots in order for them to be counted, but the date requirement has proven to be tricky for voters, and has drawn challenges from voting rights advocates. Roughly 8,500 ballots, or 1.22% of those returned, were rejected during the April primary for lacking a proper date or signature or for being returned without a secrecy envelope, according to an analysis of Department of State data.

With the November presidential election again expected to be close in Pennsylvania, even a small number of ballots rejected for technicalities like lacking a date could prove consequential for the outcome.

Problems with year show up in 2024 primary

In November 2023, the Department of State announced a redesigned ballot return envelope that it hoped would cut down on the number of rejected ballots. The new design had a shaded area where a voter would sign and date the envelope, to make it stand out, and had the first two digits of the year — “20″ — prefilled to deter voters from writing the wrong year by mistake. The state also changed the color of the inner secrecy envelope a voter must use to yellow and added watermarks to identify it.

In the April primary, the first election in which those envelopes were used, fewer ballots were rejected for voter errors. But as completed mail ballots came in, election officials around the state started to notice that many of the envelopes they were receiving had a problem: Voters hadn’t filled in the last two digits for the year in the date field.

After several counties reached out to the Department of State about how to handle these ballots, Deputy Secretary for Elections Jonathan Marks sent an email to counties advising them to count ballots even if the envelope didn’t have the last two digits of the year.

“It is the Department’s view that, if the date written on the ballot can reasonably be interpreted to be ‘the day upon which [the voter] completed the declaration,’ the ballot should not be rejected as having an ‘incorrect’ date or being ‘undated,’” Marks wrote on April 19.

Not all counties followed that advice, however. At least 22 counties opted not to count ballots missing the “24,” according to a Votebeat and Spotlight PA survey of elections officials.

An analysis of Department of State data found that the overall rejection rate for mail ballots went down following the redesign, compared with the 2023 primary. But counties that Votebeat and Spotlight PA identified as choosing not to count ballots missing the “24″ had virtually no decrease in the rejection rate as a group, and most saw an increase.

The Department of State said its analysis showed older voters were more likely to return ballots with errors that led them to be rejected.

This means the decision to prefill the full year is likely to prevent voters from making the mistake and further reduce the number of ballots rejected over issues with the date.

It would also resolve disparities among counties in how these ballots are handled, an issue that has sparked lawsuits on both sides of the decision.

Centre and Luzerne counties were sued, by the county GOP and a GOP candidate, respectively, for counting the ballots. The Centre County case was dismissed at the county court level on technical grounds, and the Luzerne case is currently being appealed to the state Supreme Court.

The Department of State argued in the Luzerne lawsuit that writing a year on the ballot was not necessary to satisfy the dating requirement. Asked why the state didn’t just do away with the year field altogether, Schmidt said that could be an option, but including the year makes it more clear when the ballot was voted and prevents further litigation over the issue in November.

Meanwhile, Lancaster County was sued for not counting the ballots, by the Pennsylvania Alliance for Retired Americans. But the group dropped its lawsuit last week after seeing the new Department of State directive on preprinting the full year.

Schmidt added that the litigation over this issue also motivated the department to issue the directive.

“With the presidential election ahead of us, and very strict deadlines for certification of election results at the county and state level, we thought it would be important to do our part to keep counties out of all this litigation,” he said.

Schmidt also noted that it took more than two months after election day for an appeals court to rule in the Luzerne case, which would have pushed the state well past the federal certification deadline had it been initiated after the November election.

“This is certainly a desired outcome, and much faster than going through litigation,” said Nina Beck, an attorney with Fair Elections Center, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on voting rights, which represented the retiree group in the Lancaster case.

“We’re happy to have a uniform mandate across the state.”

How counties will handle the change

Election officials said it had become clear in recent weeks that the department was moving toward making a change to the date field.

Some counties were considering printing the full year on the envelope even before the directive.

Abigail Gardner, communications director for Allegheny County, home to Pittsburgh, said the county was talking to the company that prints its mail ballot envelopes about the feasibility of adding “24″ to envelopes that had already been printed.

“It was just obviously one of the biggest pain points for ballot errors, so it seemed like a smart fix,” she said.

Schmidt confirmed that other counties had been seeking permission from the department to preprint the full year.

Costs are likely to be low, Fayette County elections director Marybeth Kuznik estimated. Her county uses the same printing company as Allegheny and Philadelphia, Phoenix Graphics. She said that the directive was not a surprise.

“At this point, there have been so many changes and court cases, nothing surprises me anymore,” she said. She’d like the legislature to take up the issue to make sure a mail ballot envelope requires only critical information from the voter.

“We know when we mailed [the ballots] and when we get it back. The date in between is not useful to us,” Kuznik said.

A pending lawsuit filed in May by the ACLU of Pennsylvania and the Public Interest Law Center seeks to invalidate the dating requirement altogether, but for now voters will still need to write at least the month and day on their return envelope.

As counties move forward with adding “24″ to old envelopes or printing new ones, they will need to estimate how many envelopes they’ll need for a given calendar year, so they don’t waste money on envelopes that can’t be used in future years.

While state law spells out how many ballots a county must provide for in-person polling places, it doesn’t specify a number for printing envelopes, Beaver County elections director Colin Sisk said.

Sisk said he imagines most counties will err on the side of over-ordering.

But overall, Sisk said, any time counties can get direction that has the force of law, it helps streamline processes and create more uniformity across the state.

“The most important thing we can have is a consistent approach across the counties,” he said.

Now, he said, it’s just a matter of “getting voters to know they still need to put the month and the day.”

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.