Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Pennsylvania’s free newsletter here.

Update, 7:10 p.m., Oct 23, 2024:This story has been updated with news of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision on provisional ballots.

Update, Oct. 26, 2024: This story has been updated to reflect changes this past week to Indiana County’s policy, as well as information on Mifflin County’s policy.

Voters in most Pennsylvania counties will have the chance to fix errors with their mail ballots during this election and spare them from being rejected, according to a review of county policies by Votebeat and Spotlight PA.

Thirty-eight counties allow voters to fix errors with their mail ballots in some way.

The practice, referred to as notice-and-cure, is a policy some counties have adopted to inform voters of errors with their mail ballots that put those ballots at risk of rejection and allow those voters to correct the mistakes.

At least 26 counties, however, will not offer voters the chance to fix errors, according to the survey. But in light of a new ruling from the state Supreme Court, counties will at least have to accept valid provisional ballots cast on Election Day by those voters.

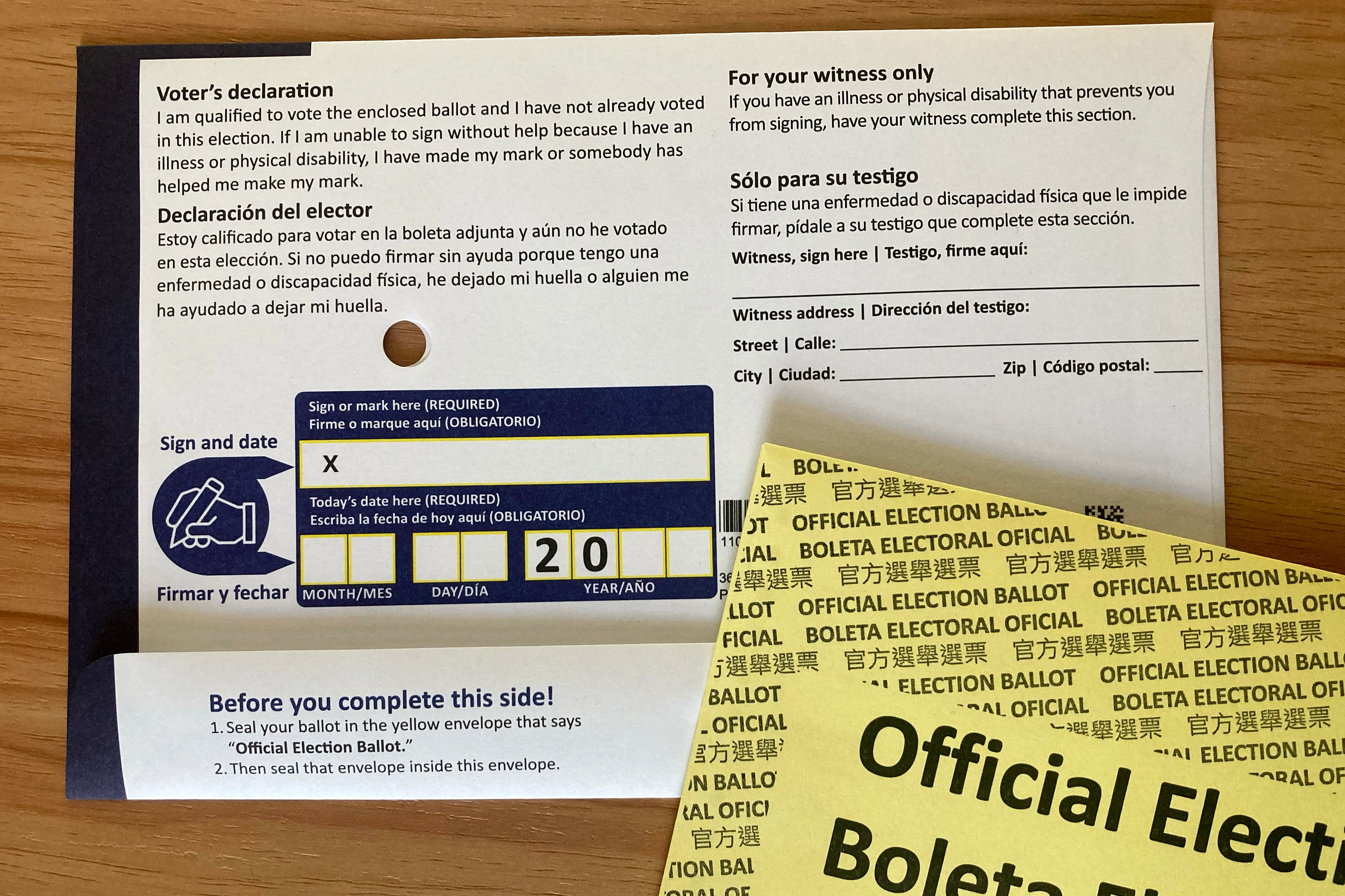

The rules that can lead to mail ballots being rejected are outlined in Act 77, the 2019 law that expanded mail voting in Pennsylvania. It requires that voters place their ballot in a secrecy envelope before placing that envelope in the return envelope, and that voters sign and put the current date on the return envelope. Failing to do one of these things will prevent the county from counting the ballot.

Precisely how voters can fix these mistakes varies from county to county, creating a patchwork of policies around the state that can sometimes be confusing for voters and advocates to keep track of.

Some counties, including Allegheny, send the defective ballot back to the voter with instructions on how to fix the error, as well as a new return envelope. Chester County tells voters to come into the elections office with ID and fix it in person. Delaware County cancels the defective ballot and issues a new one.

How successful curing is also depends on the method. A spokesperson for Allegheny said that voters there fixed nearly 62% of defective mail ballots in the spring primary using its method. Data from Fayette County shows a roughly 50% cure rate this past election. In Venango County, roughly 40% of ballots at risk were fixed and counted.

The variation comes from the fact that curing is not a process defined by the state’s election code. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has held that while counties aren’t required to offer an opportunity to cure, the law doesn’t prevent them from doing so either.

Some counties have interpreted that lack of clear direction to mean that they shouldn’t allow curing.

“Our board has consistently taken the stance that the law does not tell us, it doesn’t say we ‘shall’ cure ballots,” said Joe Kantz, chair of the Snyder County Board of Commissioners. “So because of that, we don’t. Because when people go outside of what the law tells them to do, that’s not usually a good thing.”

Kantz, who formerly served as the chair of the Election Reform Committee in the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania, said many other counties take that viewpoint. He said he “would love nothing more” than to have uniformity across the state, but he said that requires legislators to “do their job.”

“I’m not saying either side is wrong or right, but what we need is clear definition in the law,” he said. “This is a pretty simple issue: Either we are going to cure, or we are not going to cure. So give us some clarity in the law.”

Since 2020, the legislature has tried to clarify what curing means and whether counties should be able to allow it, but no legislation has made it through Harrisburg’s partisan gridlock.

The state Supreme Court has just resolved one such question, and stands to provide clarity on another.

The court ruled late Wednesday in one case, from Butler County, that dealt with whether voters whose mail ballots are rejected have the right to cast provisional ballots at their polling place on Election Day and have those votes counted. The 4-3 decision found that these ballots must be counted.

The other case, from Washington County, deals with whether counties are required to notify voters when they are going to cancel the voter’s mail ballot due to defects. The court has yet to rule on that case.

For now, counties continue to navigate this lack of clarity on their own. Just last week county commissioners in Bradford County, which previously allowed curing, voted to discontinue the practice, while Indiana County changed course in the opposite direction, voting to allow curing.

The analysis by Votebeat and Spotlight PA also shows that, contrary to popular belief, notice-and-cure is not a strongly partisan issue. Thirteen counties that Joe Biden won in 2020 have implemented the practice, but so have 25 counties that Donald Trump won.

Fayette County, in south central Pennsylvania, is one of the Trump counties that have a notice-and-cure policy.

Sophia Murray and her husband, John, both submitted mail ballots to the county during the primary, but they had the wrong date on the envelope.

Sophia said she and John, who are both in their 70s, wrote the wrong year or day of the month. Data shows ballot errors tend to affect older voters more frequently. But the county called to let them know, and they both were able to fix the problem and have their vote counted.

“It was really great that they let us do that,” she said. “They let us save our vote.”

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.

Correction, Oct. 29, 2024: This story has been updated to reflect that Cambria and Lackawanna counties do allow ballot curing in person at the county elections office.