A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

My heart, it breaks, because the focus this week is back on my home state of Texas. Houston state Sen. Paul Bettencourt has proposed a two-part bill, the second half of which is supported by Donald Trump and would require all of the counties to audit the 2020 election at a cost of, according to a nonprofit’s projection, $250 million. This is the high end of one estimate, but experts say an audit is not likely to be materially cheaper than that, especially when you factor in election equipment that might need to be replaced after third parties tinker with it — invalidating the machines’ certification — and the incredible workforce cost of conducting something like that in a state where 11.3 million people cast ballots last year.

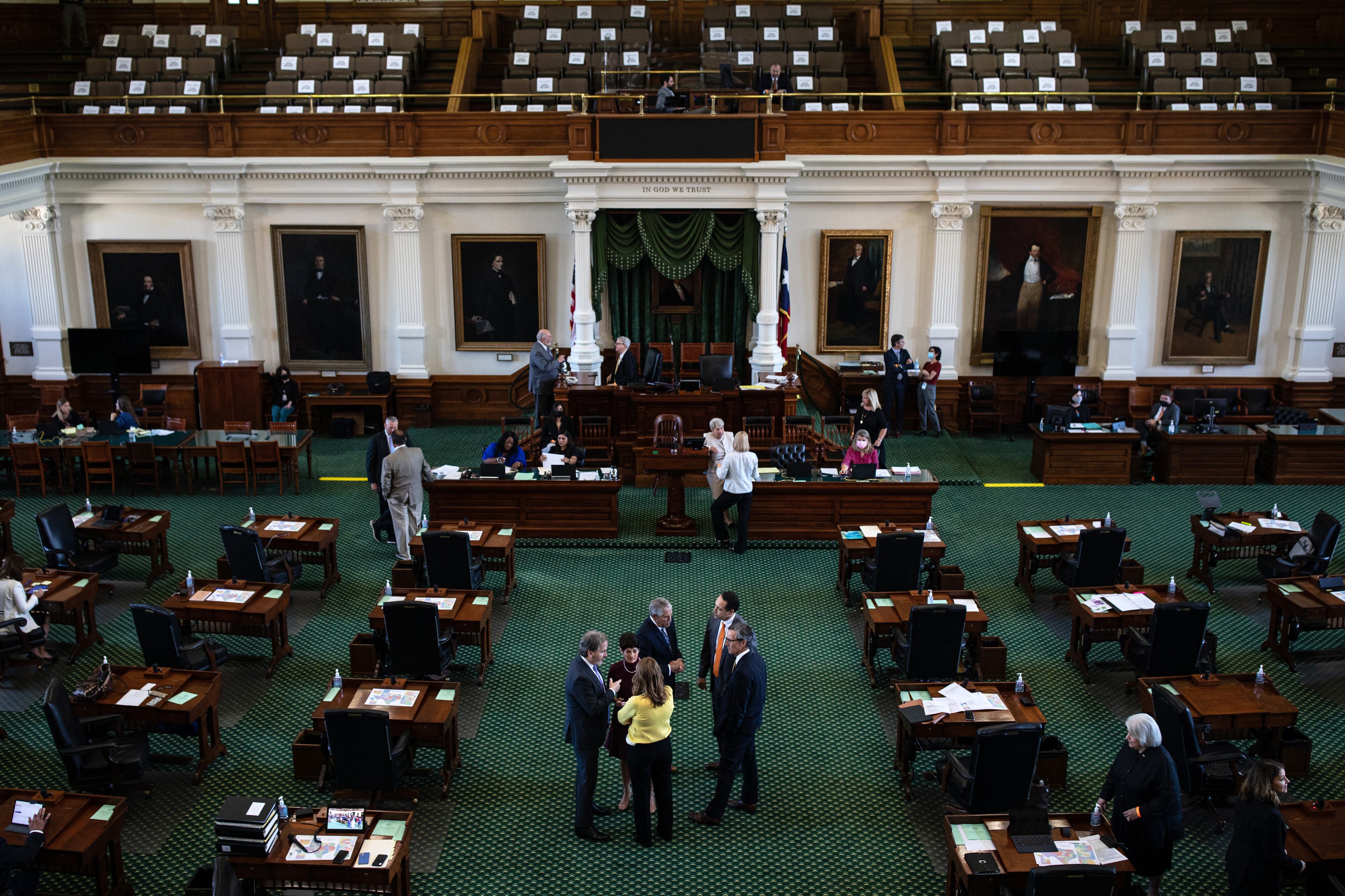

Let’s stop to think how needless this gargantuan effort would be, considering that Trump won this state. If even a winning candidate can demand a recount, where does it end? At what point do we cut our elections administrators, and frankly our system of democracy, a damned break? The Texas House may be doing just that. While the Senate passed the bill last week, the House hasn’t taken it up. As I learned through my reporting during the last special session, House Republicans — buoyed by Speaker Dade Phelan — are reluctant to pass draconian voting legislation, and this moderating impulse is what kept much of the most heinous ideas out of the Texas election bill that passed this summer.

The first part of Bettencourt’s bill is, really, not that concerning, say experts I’ve spoken to. It creates a formal process by which a candidate, party chair, judge, or the leader of a political committee related to a ballot measure can formally ask the county for an explanation of an irregularity, which the county would have 20 days to provide. If they are not satisfied, they can ask the secretary of state’s office to look into the issue further. But the secretary of state’s office, historically, has agreed with the counties on election disputes. Many news outlets have characterized this section as recounts-on-demand, but that’s not my read of the bill. Before an audit could happen, the citizen would have to take their claim to the SOS’s office, which would determine if an audit was reasonable. The secretary of state has historically not bucked the decisions of counties, and voters can already come directly to the office with concerns. So while this might open the door to more audits, it doesn’t seem likely that these audits would spiral out of control.

Left-leaning activists have largely also ignored this section, but to the extent that they’ve acknowledged it, their criticism is the same as for the 2020 statewide audit: This would consume tons of time for county clerks, who would be forced to respond to politically motivated questions. But really, they are already doing that. The 20-day deadline to respond is double the amount of time that clerks get to respond to public records requests in Texas, and many of these questions could be answered through records or seeking this information without a formal process. Clerks already answer these requests, and have no formal way to proceed if the requestor disputes their findings. Now, the clerks do. They can send the request up to the secretary of state’s office, who will provide the same explanation but with more force.

State officials I’ve spoken to in Texas say this is a fine idea. But this section of the bill has been glossed over in news coverage and with Republicans who are discussing the bill — because of course, an impending audit that costs $250 million is going to overshadow a review procedure. (The same amount of money, per the budget passed this year, could fund the salaries, benefits, travel, and expenses of the entire workforce of the attorney general’s office.)

The 2020 audit was affixed to this bill in order to make it more salient during this very weird time in election politics — the first section, which would lead to transparency, is boring to the base. Slap an audit on there that Trump wants? It’s basically legislative hot sauce. It is a strange moment when Republicans are motivated by a deeply unnecessary and transformatively pricey government action. This feels like we’re in the twilight zone.

Let’s consider, for a moment, the logical extension of this type of messaging. On Wednesday, Donald Trump sent out a statement (since he can’t tweet anymore). It said, “Republicans will not be voting in ‘22 or ‘24” if the fraud his campaign “conclusively” documented is not dealt with. A spokesperson for Trump clarified: Trump wasn’t saying not to vote, she said, rather “if we don’t fix our elections, many voters will think their vote won’t count.”

Well, they already do. For instance, more than 750,000 Georgians who turned out for the November general stayed home for the Jan. 5 runoff. I was in the war room with the Georgia SOS staff as the results came in, sitting next to Secretary Brad Raffensperger, a Republican. When it was clear that both Democrats would be headed to the Senate, something initial results from the general election and polling did not anticipate, Raffensperger looked at me and said, “Trump did this.” And he did. Apparently he’ll keep doing it as long as Republicans stand by and say nothing, demanding audits even in states that he won.

I suppose that, yes, Trump did not literally tell Republicans, “Don’t vote” — he said that Republicans won’t vote. Trump’s team seems comfortable with this, but it’s not clear if they’re comfortable with repeatedly losing because their boss suppresses his own voters.

Back Then

Those who highlight accusations of fraud love to talk about the fraud that used to happen here. LBJ stuffed ballot boxes. Party bosses paid the poor. But what if the basis for these accusations was not as solid as many believe? Alexander Keyssar — my voting guide in all things — writes, “on the one hand, fraud and corruption clearly did exist: complaints came not only from upper-crust reformers but from labor organizations and Populists.” But, the reformers themselves had questionable motives: “Their antagonism towards poor, working-class, and foreign-born voters was thinly disguised at best, and many of them unabashedly welcomed the prospect of weeding such voters out of the electorate.” In recent years, political scientists have been studying this history more fully, and what they’ve found sounds eerily similar to today. Keyssar writes, “Most elections appear to have been honestly conducted: ballot-box stuffing, bribery, and intimidation were the exception, not the rule.”

In Other Voting News

- Politico is out with a fascinating look into the (possible) future. If Trump runs again 2024 and wins, his call to “reform” elections to deal with “fraud” will become a full policy agenda - not just a talking point.

- Yet another judge in Arizona has disagreed with Senate Republicans who continue to try and keep documents about the “audit” there secret. “It is hard to imagine more serious litigation than the disclosure of documents underlying an audit of the election of the president of the United States and a United States senator in Maricopa County,’’ Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Michael Kemp wrote.

- Mesa County Clerk Tina Peters will not be allowed to manage her county’s election in November, a district court judge in Colorado has ruled. The judge found the state had sufficient evidence that Peters had “committed a breach and neglect of duty and other wrongful acts.” In a statement, Peters called the decision a “power grab” and said she intends to appeal.

- Counties in Florida say they each need several thousands of additional dollars to comply with Florida’s new election law. At least one county is removing drop boxes in order to save money. In St. Augustine County, a right-leaning county, there will now be one drop box. In 2020, there were 10.

- The national poll worker shortage has hit Ohio, where Secretary of State Frank LaRose says they are “putting out the help wanted sign” because the state is short a whopping 17,000 poll workers for its upcoming local elections. Poll workers in the state are paid about $200.

- The ambition of the Republicans’ investigation of Wisconsin’s 2020 election seems to be shrinking. Election officials who were initially subpoenaed to testify will now provide documents instead, the AP reports. The lead investigator has said that those individuals who do not cooperate will be required to testify in person.

- After an administratively smooth but politically chaotic recall election, California Democrats are now zeroing in on reforming the state’s century old rules governing the move. A special committee is reviewing the issue, and legislators anticipate seeing reform legislation during the 2022 session.

- Trump supporters plan to go door to door looking for “ghost voters” in Michigan, who are alleged to have cast ballots despite not existing. No proof of this phenomenon has been found. Federal officials have already warned the move could constitute voter intimidation. A bill there that would only allow a provisional ballot to be counted if an ID is shown after it is cast, and removes exceptions to the ID rule in place is also now headed to the governor’s desk, though she is expected to veto it.

- We’ve found it, the world’s greatest election headline: “Costume Confused For Election Drop Box Not Part Of Illegal Activity.” Apparently the folks who run Bucks Voices, an advocacy group in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, made — and I am not kidding at all — ballot box costumes so they could dance around in them to advocate for more drop boxes. If you don’t believe it, there is video. But one costume, which was apparently inadvertently left on the steps of the town hall, caused some confusion. Apparently voters thought it was real, and dropped six ballots in there, and someone complained to the local county attorney. The ballots have now been properly cast, and the county removed the cardboard costume, which, in fairness to Bucks Voices, was festooned with signs that said “COMING SOON.”

Good Idea of the Week

At our panel event this week, CTCL executive director Tiana Epps-Johnson and former secretary of state Trey Grayson touched on something we’ve talked a lot about in the Votebeat newsletter: The need for election administrators to be more transparent with the public about procedures and safeguards. And we have one great example of that. Benton County, Iowa held public tests of their voting machines on Monday, which they also streamed on Facebook Live. In the video, Gina Edler, the county’s auditor, and her deputy walk through every step of the process, showing the machines and the process of the logic testing, right there on the screen! The local news calls it “worth a watch,” and we agree! For the sake of voters, please do more of this!