This article was co-published with Texas Monthly.

When Greg Abbott selected John Scott last month to serve as Texas’s top election official, the move generated little local controversy—a striking achievement in a state where the two major parties have staked out what they say are diametrically opposing views on voting. Republicans in state politics, predictably, welcomed Scott, a conservative Fort Worth attorney who was briefly hired by the Trump campaign to challenge election results in Pennsylvania last year. More surprising was that Democratic lawmakers, who only months ago fled to D.C. to protest an expansive voting bill, also largely embraced him, after a brief recoil, as the best option possible.

“You know, [Scott] called me to tell me he was being nominated, and I said, ‘You know I’m going to be suing you?’” said Roland Gutierrez, a Democratic state senator from San Antonio, who has filed a complaint in federal court over Republican redistricting in the state. “We’ll go to court, and then we’ll have a beer.”

“I never agree with Greg Abbott on much of anything, but at least with John Scott I know that he’s a competent person, a good person, and a good lawyer,” Gutierrez added. “This is a contact sport and I’m all about fighting the good fight, and I feel comfortable fighting that fight against John Scott.”

It’s a strikingly cordial tone in a state in which the debate over voting rights has reached a fever pitch. The Secretary of State is Texas’s chief elections official and is responsible for issuing guidelines to counties on complying with state and federal voting laws. The secretary also oversees election audits and voter roll maintenance. By picking Scott, Abbott, who has not shied away from taking full-throated partisan positions on everything from border security to making it more difficult to vote, may have found the single person capable of satisfying both parties. While he has the backing of Trump supporters, he also is an experienced bureaucrat who told me over coffee this month that he does not believe voter fraud swung the 2020 election.

Unlike previous appointees to the role, who were selected for their interest in Mexico policy or economic development—other components of the Secretary of State’s job—Scott also has experience with elections and running large agencies. He served as the Texas deputy attorney general from 2012 to January 2015, and earned a reputation as a fair but fierce attorney for the state. Abbott then tapped him to be the chief operating officer of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, a 56,000-person agency that is several hundred times the size of the Secretary of State’s office, and Scott later served as chairman of the board for the Department of Information Resources, which provides IT services to state and local agencies. Gutierrez and Senator Judith Zaffirini, a Democrat from Laredo, say he excelled in both roles and will be able to deftly navigate the oddities of Texas state government from day one.

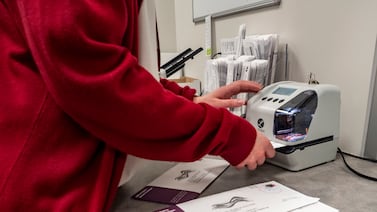

In recent decades, secretaries have viewed responsibility for elections, and coordination with county elections officials, as secondary to border policy, diplomatic relations with Mexico, and economic development. Scott already has shown that he sees the role differently, visiting three elections offices in the first six days of his appointment and scheduling a drop-in at a fourth. He said he thinks Abbott chose him because of his specific interest in and knowledge of elections. “I think it’s the only reason I was picked,” he said.

Scott told me when we met in Dallas that his top concern is “bringing the temperature down” on voting by engaging more directly with local election officials and being transparent with the public about the voting process, all in an effort to create a common set of facts both parties can agree on. “If I can walk away and people go, ‘Hey, it works—the system is good,’ I can ride off into the sunset and go back to my happy old life, extremely pleased. It’s a worthy effort.” Five Republican and Democratic state senators I talked to told me he might be the only person in the state who can pull it off.

Nonetheless, it would be tempting for Gutierrez and other Democratic senators to write off Scott’s nomination on its face. Abbott has repeatedly claimed that voter fraud plagues elections, has asserted without evidence that thousands of illegal immigrants are registered to vote in Texas, and called multiple special sessions this year to force the passage of a controversial election bill. Given his zeal, Democrats worried that he would nominate a hard-liner who would allow Abbott, who’s up for reelection, to satisfy Trump voters as he battles two right-wing challengers in the GOP primary. Because Abbott waited until after all three of this year’s special legislative sessions to fill the Secretary of State position, there was also worry the nominee would run rampant without legislative oversight until facing confirmation in 2023, when the state Senate reconvenes. “I was really concerned about who [Abbott] would select,” said Zaffirini. “I was shocked when I found out it was John. Shocked. He is an absolutely wonderful attorney—I have referred friends to him for representation.”

Other aspects of Scott’s record offered Democrats some cause for concern. As the state’s deputy attorney general, he defended in court Texas’s controversial voter ID law, which initially required all voters to provide specific photo identification, barring those without it from casting a ballot. (Litigation continued for almost two years after Scott left the office, and the law ultimately was partially struck down.) And in late 2020, the Trump campaign hired him, alongside Republican state senator Bryan Hughes of Mineola, to represent it in one of a flurry of lawsuits it filed to challenge the election result. A handful of counties in Pennsylvania had notified voters whose initial ballots were rejected, allowing them to correct them, and Trump was arguing that those ballots should be thrown out because voters in the rest of the state were not offered such an opportunity—though Pennsylvania law does not bar counties from the practice.

Though he doesn’t believe voter fraud tilted the election, Scott told me he felt the campaign had a strong equal-protection claim to make, even if it was always going to be a difficult case. “These aren’t the greatest cases in the world,” he told me, referring to equal protection litigation concerning election procedure. He only lasted one business day on the case. An appellate court ruled that the campaign had no standing on the issue, and Scott and Hughes withdrew—even as elements of the case continued on in lawsuits tried by other attorneys, until the Supreme Court eventually declined to hear it. “There wasn’t anything else to do,” Scott said of his decision to withdraw.

The brief representation set off alarm bells on social media and in some Democratic circles after Scott’s appointment. Jessica González, a Democratic House member from Dallas, said she believes the association with the lawsuit alone to be disqualifying, calling Scott’s selection “irresponsible.” Representative John Bucy of Austin said that he’ll reserve judgement on Scott, but that his work on Trump’s lawsuit gave him “real pause.”

Other Democrats said they see the brief association as a potential benefit. “If anything, I’m more confident,” said Zaffirini. Republicans will trust him, she and Gutierrez both said, because he has the Trump bona fides, and Democrats don’t have to be worried about his integrity. Both senators said they were pleased that Scott allowed the facts of the Trump case to guide his decision to end his participation. “He’s careful and honest,” said Gutierrez, who told me he and Scott have spoken extensively about the case, and that he is satisfied that Scott chose to represent the campaign “in good faith” before he realized there was not a firm enough basis to continue.

Gutierrez recognizes that Democrats who share his views on voting are likely to have a more negative impression of Scott’s brief dalliance with the Trump campaign. But he said Democrats do not have the power to throw roadblocks in front of the governor’s selection. “As long as Democrats don’t vote and get these people out of power, we are going to be subject to whatever nominee this man [Abbott] wants, for the most part. Our ability to fight these nominations is limited,” he said. Like Zaffirini, he found himself shocked that Abbott would select a person who is “partisan, sure, but not an ideologue.”

Across the country, secretaries of state are playing a far more public role now than they once did. What was once a bureaucratic, even sleepy, position in state government now comes with intense scrutiny, constant threats of litigation, and even threats to personal safety. That is especially true of the position in Texas. While Trump’s many 2020 lawsuits were the legal equivalent of a long, deflating balloon sound, his impact on the state has only swelled in the last year.

Earlier this fall, a day after Trump requested additional scrutiny of the election results in Texas despite his victory in the state and no evidence of misdeeds, Abbott introduced an audit of the results in the four largest counties. The move drew criticism from Democrats, but Scott said he hopes the audit will codify a “common set of facts” between the two warring parties. If they are working with the same information, he believes, they will come to more similar conclusions. He wants it to become a model for how other states can use audits to offer reliable data and meaningfully improve the system, rather than serve to sow doubt. To that end, the Texas audit he will oversee will be notably different from the one Trump called for. It won’t encompass the whole state, and the audit will be bipartisan, run by the state and counties, rather than an outside contractor as in Arizona and Wisconsin. While counties in those states loudly protested Republicans’ reviews, none of the four in Texas have meaningfully pushed back against Abbott’s demand.

Scott told me he does not believe that mass fraud will be found. He said he wants the process to be a fair, good-faith assessment of how well the system works. “I want to illuminate the efforts that go into having a fair election, because I think anybody that thinks they’re not having a fair election may decide not to vote.”

Not all Democrats are buying it. González said the audits begin from the premise that there is something wrong with the system. “Why audit something that works? That’s not why Trump asked the state to do this,” she said. “I think this will backfire.” She isn’t convinced by Scott’s reasoning for joining Trump’s lawsuit, either. She called his appointment “another way to placate Trump.”

As Secretary of State, Scott will almost certainly be caught up in litigation challenging Texas on its voting law passed in the wake of Trump’s questioning of the election result. The Department of Justice brought a suit this month, targeting provisions in the law that criminalize mistakes made by those assisting voters who need help casting a ballot, and a provision requiring voters to provide an identification number on applications for absentee ballots and their envelopes that matches what the state has on record. The latter provision introduced a problem documented by Texas Monthly and Votebeat in July. Some 1.9 million Texans are lacking one of two possible identification numbers in the voter roll, either a driver’s license number or a Social Security number. An absentee voter who incorrectly recalls or guesses what number they used to register initially will have their application or ballot rejected. Legislators partially addressed the issue, but the final version of the bill still relies on voters to take several steps on their own to correct the missing information. Scott declined to answer questions about the law, citing the ongoing litigation.

As he steps into the fire, Scott is likely to be better prepared than Abbott’s last two choices for the office, who saw their nominations fail before the Senate largely because of partisan election controversies. David Whitley, who had the job in 2019, served for only six months before resigning after his office presented counties with a deeply flawed list of what it claimed were thousands of “possible non-U.S. citizens” on the voter roll. Democrats demanded accountability, and civil rights groups successfully organized to block his confirmation. Ruth Hughs, his successor, resigned from the post in May, after declaring the 2020 election to be “smooth and secure,” causing ire among hardline Republicans. Staffers of the Secretary of State’s office and two Republican legislative aides said they believed Hughs actively stayed away from elections after watching Whitley’s downfall: she rarely visited local election offices, and county election administrators interviewed for this piece could not remember having specific conversations about election policy with her.

Scott said he isn’t worried about getting caught up in partisan drama. Because he’s never held elected office, he says he is inherently less ideological than many of his critics believe given his résumé. And because he’s uninterested in future government jobs, he said, there will be no need to inflate his reputation within his party. “I am trying to be as neutral as possible, because I think the one thing [we need to do] to bring credibility into the system is to be able to speak for both groups,” he said. “It’s like, Stop, you know? You can have your debates on policy, but don’t have your debates on whether we have fair elections. That’s what I want. That’s the end game.”