For more than a year, a coordinated group of Texas activists have mounted a statewide effort to further former President Donald Trump’s lies about the 2020 election: They’ve sent voters hundreds of postcards requesting personal information, questioned residents at addresses pulled from voter rolls, and examined thousands of ballots for unspecified irregularities.

So far, despite the work of what they say are dozens of steadfast volunteers across the state, they’ve offered no compelling evidence of mass fraud.

That isn’t slowing them down.

“We are a grass-roots organization in Ft. Worth/Tarrant County that has been praying and seeking God’s guidance regarding suspicious election statistics following the Nov 2020 elections,” members of the Tarrant County-based group wrote to the secretary of state in an email late last year. He met with them a month later, but said nothing came of it.

Similar efforts by affiliated groups are taking place in Harris, Hays, Travis, Williamson, Bexar, Bell, Collin, and Dallas counties. But the work appears to be rooted in Tarrant County, home of Fort Worth — Texas’s reddest major city whose future as such remains unclear.

This work echoes efforts nationwide by allies of former President Trump who have been sowing doubts about the integrity of the vote, advocating for the creation of groups such as this one to investigate and monitor the administration of elections at a local level.

Interviews with more than half a dozen local and state officials, as well as emails obtained by the watchdog group American Oversight and shared with Votebeat, paint a vivid picture of a coordinated network of activists eager to find an audience for its claims. Officials say the group has offered no valid evidence of fraud despite a relentless and wandering investigation.

“Texas voting processes are not okay,” the network’s leaders wrote on an informational flier earlier this year. The conspiracy-laced screed featured a QR code linked to a 13-minute video by embattled Colorado clerk Tina Peters, who by that point had been charged with a list of federal and state crimes for tampering with election equipment and was running for the Republican nomination for Colorado Secretary of State. She would later lose handily, blaming fraud.

Mobilizing on the ground

In early 2021, the network of activist groups began filing public records requests seeking voter rolls and the ability to inspect physical ballots in counties across the state. Once they got access to the voter roll — a public document — their on-the-ground activity began in earnest. In June of last year they sent canvassing postcards to Fort Worth voters asking them to enter their personal information into a website, to ensure “no irregular votes were added and that people’s votes counted” in the 2020 election. Voters, alarmed, contacted state and local elections officials to ask if the inquiries had come from them. They had not, and voters were told to give the group no information.

By July 2021, volunteers were knocking on doors in Tarrant County attempting to verify voters’ addresses and ask whether they had voted. Since then, affiliated groups have done the same in Collin, Hays, Harris, Travis, and Williamson Counties. They claim they’ve knocked on more than 10,000 doors.

The emails provided by American Oversight show the level of coordination between the Tarrant County group, called Tarrant County Citizens for Election Integrity, and like-minded organizations across the state. Most notably with Alan Vera, the chair of the Harris County Republican Party’s ballot security committee, who has been baselessly sounding the alarm on voter fraud in Texas for the better part of two decades. The Harris County Attorney’s Office announced in July it was investigating allegations of Vera’s group — the Texas Election Network — knocking on doors, verifying voters’ addresses and asking them to sign affidavits.

Vera did not respond to a request for comment, and no one could tell Votebeat what, if anything, had been learned from knocking on so many doors. Dan Bates, a Fort Worth attorney who is the Tarrant County group’s head counsel, presented no evidence that could be successfully used to prove fraudulent activity.

A fruitless effort with the secretary of state

His group also came bearing little in the way of proof in December 2021, when he and eight others successfully invited newly appointed Secretary of State John Scott for breakfast at the Colonial Country Club in Fort Worth — a swanky, members-only golf club with a reported $80,000 initiation fee.

Scott, who briefly represented the Trump campaign in a challenge to election results in Pennsylvania before backing out due to an absence of evidence, began receiving emails from the group shortly after Gov. Greg Abbott tapped him for the position less than two months before.

Buff Kizer, a Fort Worth resident and self-identified part-time chaplain, wrote to Scott in November 2021 offering to show Scott “findings of voter rolls and voting issues” in Fort Worth and Tarrant County, including vacant lots, fictitious addresses, and “excessive number of votes from a single address.”

“They did provide a packet of information, I flipped through it,” Scott told Votebeat. Although he turned the packet over to his office’s audit division, nothing came of the complaints. Scott wouldn’t say whether he shared the group’s concerns of voter fraud, only that he acknowledged they have a right to raise them and show their evidence.

“We want the information. And to the extent the information turns out to be relevant, great. To the extent it proves to be irrelevant, then we’ll make sure they understand and we can document why we believe it is irrelevant,” Scott said.

There are legitimate reasons why a voter might list a vacant lot or a P.O. Box on their voter registration forms, Sam Taylor, assistant secretary of state for communications said. Laws protecting the personal information of domestic violence victims, peace officers, and certain public officials allow them to keep their address of residence withheld from public release or anonymized, and voters without a permanent or stable address can register using alternative addresses.

“For example, if a homeless person wants to register to vote, they can say, ‘My residence is at the corner of I-35 and Cesar Chavez.’ And they can put a PO Box as their mailing address,” Taylor said.

Additionally, multiple voters registered at one address could mean that a family of four adults at one location are all registered to vote.

Bates said he and the group are unsatisfied with Scott’s lack of action, and the lack of action of the Tarrant County Commissioners Court.

“If our elected officials are not going to make an inspection [of the machines] we will do it and we will pay for it,” he said, expressing frustration that their requests to do such inspections have been rebuffed.

Scott said his office is already doing its due diligence. The secretary of state’s office is finalizing its own audit of the 2020 election on Tarrant, Collin, Dallas, and Harris Counties — the two largest Republican and two largest Democratic counties in the state, respectively. The first phase was released in December, shortly after Scott met with the group, and revealed no major issues. The full audit should be completed by September.

Scott was far from the only person the Tarrant County group attempted to convince to spare some time. Emails to Scott from the group state that in Collin County they have “cooperative officials at all levels.” Collin County election administration officials did not respond to a request for comment.

Emails show Citizens for Election Integrity also contacted Tarrant County Sheriff Bill E. Waybourn. A sheriff’s office spokesperson would not say whether Waybourn met or communicated with people involved with the group, noting only that “election discussions between the Sheriff and citizens have not revealed evidence of a criminal nature to date.”

Kizer told Scott by email the group also briefed Rep. Steve Toth, a Republican representing part of Montgomery County just north of Houston. Toth, Kizer wrote, “shares our concerns” and was copied on the email.

Toth’s legislative background suggests his sympathies: In 2021, Toth sponsored a bill that would have required a forensic audit of the 2020 results in counties with populations over 415,000 (there currently a dozen such counties). The bill failed.

“It is personal. I’m fed up.”

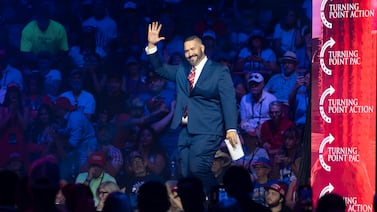

More alarming has been the spotlight the group has cast on local election administrators. In Tarrant County, an outsized share of Citizens for Election Integrity’s ire has been directed at Heider Garcia, the election administrator.

In the fall of 2020, a ham-fisted and sloppily produced video called “Who is Heider Garcia?” began making the rounds on rightwing social media. Toth, the sympathetic state representative, shared the video on his own Facebook page. “Heider Garcia of SmartMatic is grilled in the Philippines over voter fraud. He now runs election (sic) in Tarrant County, Texas. What could possibly go wrong?” he wrote in late November 2020. “Democrats play to win while Republicans play for a participation trophy.”

The video made its way onto sites like 4Chan and 8Chan, known for hate-filled content posted by conspiracy theorists, resulting in near constant harassment for Garcia. Tarrant County Citizens for Election Integrity shared the video repeatedly on its own channels.

It alleges Garcia — who worked for election technology company Smartmatic before taking jobs in election administration in California and then Texas — was involved in voter fraud in the Philippines. Garcia can be seen in the video being grilled by a Filipino lawmaker, a remnant of his work implementing Smartmatic voting machines in the country more than a decade ago.

Bates told Votebeat he is familiar with the video but does not know who created it or why, and defended it as “informational.”

Garcia said the allegations in the video are false. Notably, the Philippines never rejected voting systems by Smartmatic and continues to use them.

But Garcia worries about the safety of his family given how personal the attacks have become, he said.

“They will say these things, but then they’ll come in and they’ll be very polite and respectful. You know, like, ‘Oh, no, we know you’re a really good guy. This is nothing personal.’ I’m like, It is personal,” said Garcia. “I’m fed up with it.”

The videos and the social media posts have led to threats, Garcia said. In testimony submitted to a U.S. Senate committee this week, he included pages of screenshots of hostile social media posts and recounted a night in November 2020, after the election, when he and his wife realized their address had been posted online.

“To this day, not a single person or entity has been held accountable for the impact this whole situation had on my family and myself,” Garcia said in his testimony.

The Tarrant County group’s intimidation efforts aren’t stopping Garcia or other election workers from fulfilling their duties.

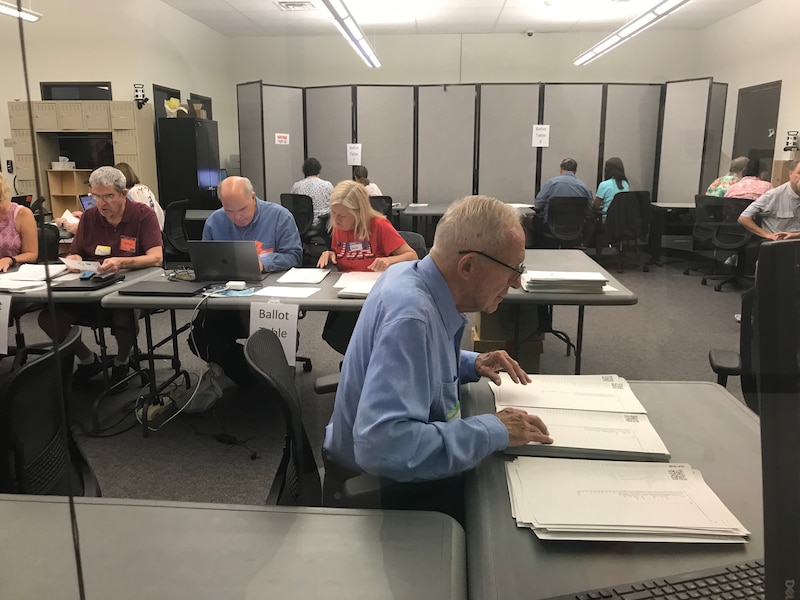

When Citizens for Election Integrity requested to inspect the paper ballots from the March 2020 GOP primary, Garcia and his staff provided the more than 300,000 ballots and space in the county office to review them. While Garcia would have been within the law to charge the group a fee for the request, he chose not to. The tallying of the ballots by the group was completed last week, though it’s unclear what, if anything, the group found. Election administrators in other counties have received similar requests to inspect ballots and have heard of door-knocking concerns.

A review of Tarrant County Commissioners Court meetings shows that volunteers have shown up at almost every single meeting since the beginning of the year, lodging repetitive complaints with hazy origins. Meetings in other counties, including Collin County and Harris County, have been similarly bogged down with these grievances.

The comments are almost identical: Speakers say there’s a need for more and independently done audits of elections in Texas. They ask to eliminate electronic voting systems and use only paper, and demand precinct-based polling places rather than countywide vote centers.

Tarrant County Judge B. Glen Whitley said he has been on the commissioners court since 1997 and has been a county judge since 2007, and has never seen the public question the integrity of elections in this way. The ongoing stream of speakers in Tarrant County prompted the court to ask Garcia for a presentation to explain elections to the public. “There were so many misstatements occurring in those public comments,” said Whitley. “So we felt like it was important to bring folks together to be able to describe [the election process] step by step.”

In April, Garcia did so. The County Commissioners Courtroom was filled to the brim, with members of the public spilling into the hallway. More than 30 people signed up to speak, many unmoved by Garcia’s explanations. “Stealing elections is stealing our country,” said one speaker, her voice shaking. “We may like big everything, but I don’t think big voting is good any longer.”

Buff Kizer — the part-time chaplain from Fort Worth who’d sent emails to Scott — spoke as well. “The manufacture of even one vote in Tarrant County is not okay,” Kizer said. “This is breaking God’s commandments and it’s something that none of us want to see.”

But that day, there were also many speakers, including election clerks, judges, ballot board members, and poll workers who expressed confidence in the system. The attacks and false claims are wearing on election workers in the county, and some said the continued onslaught is beginning to feel more and more like a personal affront.

“There are thousands and thousands of people, not the election clerks, not even candidates who work elections in our county,” Kate Duffy, a Tarrant County election judge, said to those gathered.

“There’s the pastors who make coffee really early in the morning. There’s the janitors who clean up the schools afterwards. There’s the librarians who set aside their space. And I think it’s a slap in all of our faces to say our elections are not run with good intent.”

Natalia Contreras is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org.