Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

A new state law eliminating the elections department in Harris County is likely to cause large disruptions and problems for voters in this fall’s elections and potentially 2024, experts say, throwing responsibility for dozens of state-mandated deadlines to new officials in the middle of the crucial process.

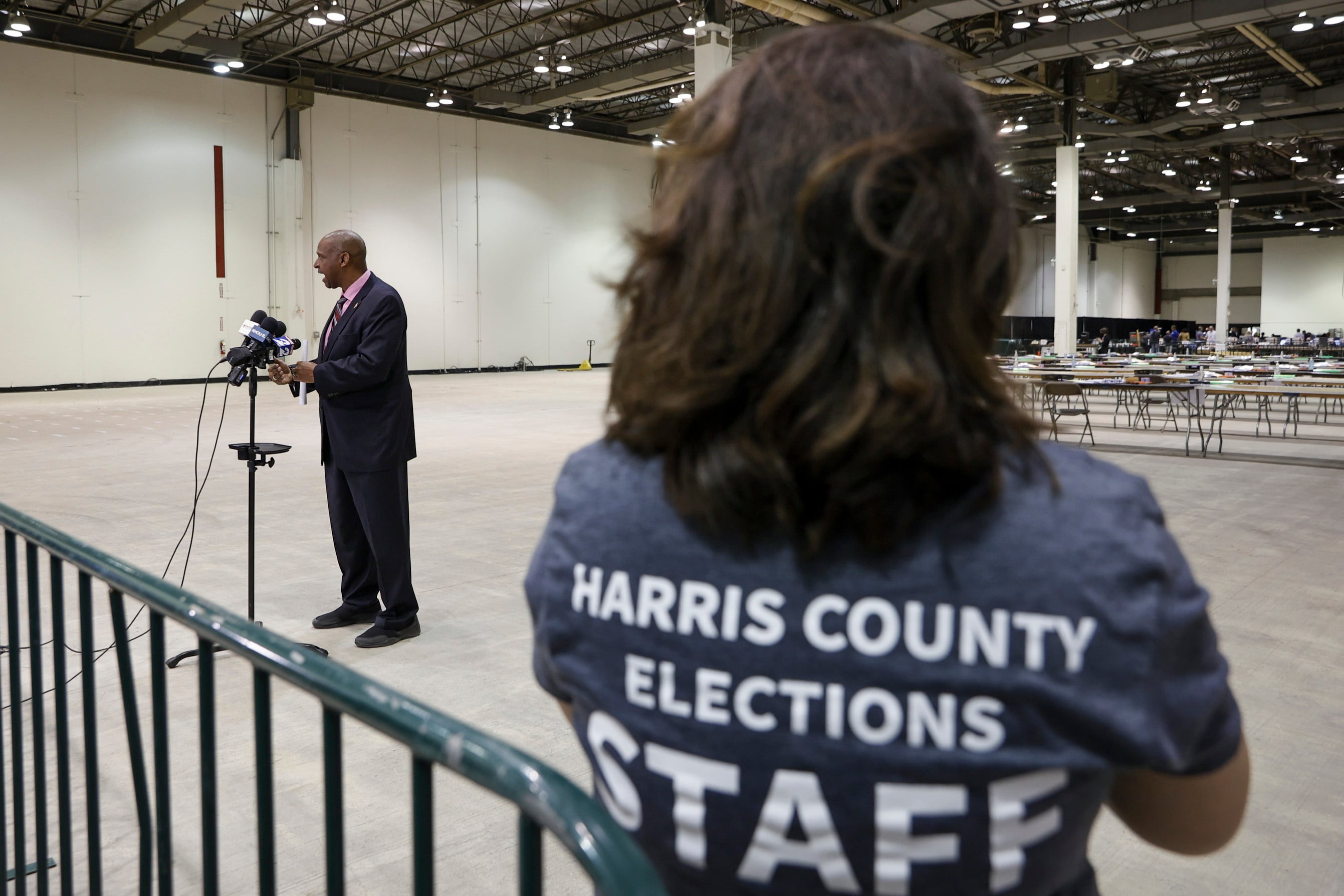

Harris County has sued to block the law, but unless a judge steps in, the county’s two-year-old elections department — currently headed by Clifford Tatum — will be eliminated on Sept. 1. The office’s duties will revert back to being split between the county clerk and the tax assessor-collector, a historic model for overseeing elections in the state that many counties have moved away from in recent years. Harris County created its elections department in 2020.

The timing of the law means the transition of election duties in the country’s third largest county would happen while election offices across the state are trying to prepare for elections this November and a presidential election in 2024, election administrators told Votebeat.

If one deadline isn’t met, it can have a negative domino effect, said Bruce Sherbet, the elections administrator in Collin County, who warned that each step on the pre-election checklist must be done in sequence for the whole thing to work.

“It’s like trying to juggle 10 balls in the air at one time. It’s very easy for one of them to drop,” Sherbert said. “And that’s when you could have situations where workers aren’t thoroughly trained and then you can have polls opening late or situations like when they’re not sure how to use the equipment.”

The potential for problems looms large in Harris, the state’s most populous county, which has been beset by controversy and stumbles since creating the elections department two years ago.

Tatum, who joined the office less than a year ago, did not respond to Votebeat’s request for comment.

But in a written statement when the law passed in May, Tatum said the “only solution” to the recurring Election Day problems is stability for the elections department. He pointed out that the new law’s effective date would be 39 days before the voter registration deadline and 52 days before the first day of early voting for a countywide election that includes the Houston mayoral race.

“We fear this time frame would not be adequate for such a substantial change in administration, and that Harris County voters and election workers may be the ones to pay the price,” he said.

Harris County sued earlier this month to stop the new law from going into effect. A court hearing has not yet been scheduled.

How the law could impact Harris County elections

Election workers in counties across the state work year-round on processing mail-in ballot applications and updating their voter registration lists. In the summer months and up to the first week of early voting this fall, election officials told Votebeat they are also busy working on a lengthy list of key tasks, all of which are time-sensitive and essential;

- Inventories of election supplies to make sure there’s enough for upcoming elections;

- Attending training to get up to speed on new election laws and how to implement them;

- Ensuring precincts are divided in compliance with the law based on county population;

- Training election workers;

- Testing voting equipment to make sure it’s running properly;

- Getting their ballots designed and proofed before they’re printed;

- Mailing out ballots to overseas military voters;

- Making sure they’ll have the number of facilities they need to use as polling locations;

- Prepping a mass mail out of voter registration cards at the end of December.

Jennifer Doinoff, the elections administrator in Hays County, which has 175,000 registered voters, said her staff has been working round the clock to do voter list maintenance and the redistricting of overpopulated precincts ahead of 2024.

Harris County, by comparison, has more than 2.5 million registered voters and last year set up 782 polling locations for them.

“What we’re doing in Hays County to prepare for November and for next year is a huge undertaking. So if it’s a big deal for us, it’s a big deal, but times 100, in Harris County,” said Doinoff.

“A change like that right before a presidential election year can set back an election department that much further,” Doinoff said, referring to the potential elimination of the elections department in Harris.

Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee made similar points in the lawsuit he filed against the state earlier this month. Menefee argues the law violates the Texas Constitution because it singles out one county. He is asking a district judge to prevent the law from taking effect.

Menefee in his filing says the elimination of the county’s elections department and the transfer of election duties to the county clerk and the tax assessor-collector — only six weeks before the November election — could lead to “not only inefficiencies, office instability, and increased costs to the county, but it will also disrupt an election the Harris County [election administrator] has been planning for months.”

“Without court intervention, the public’s selection of their elected representatives — the core process on which our democracy rests — will be risked in Harris County,” it says.

A history of problems

Harris County’s decision to combine election responsibilities into a single office in 2020 wasn’t out of the ordinary; Texas counties have a well-established right to determine how best to administer their own elections.

In the late 1970s, the Texas Legislature passed a law allowing counties’ commissioners courts, based on their individual needs, to assign election duties to the county clerk and tax assessor-collector — which are elected positions — or to create an elections department and appoint a nonpartisan elections administrator. More than half of the state’s 254 counties, large and small, have since appointed a nonpartisan elections administrator.

Harris, in fact, was one of the last large counties in Texas to create an elections department and appoint an elections administrator. County leaders initially appointed an inexperienced elections administrator, Isabel Longoria, to lead the newly created department, which had also at the time just purchased new voting equipment voters would have to learn to use. Longoria resigned in July 2022, after the department failed to report unofficial primary election vote totals to the state by the deadline required by law.

Tatum, who has years of experience running elections, inherited Longoria’s department with very little time to fix lingering administrative problems when he was appointed to his role in August.

In the November 2022 general election, Harris County had to extend voting for an hour after various polling places experienced problems with voting machines, paper ballot shortages and long waiting times. Losing Republican candidates filed more than 20 lawsuits against the county, citing those problems and seeking a redo of the election. Those are still moving through the court system.

At the time of the 2022 election, Harris County’s elections department lacked a tracking system typically used by large counties to identify issues in real-time, and for months, could not say how many polling locations ran out of paper on Election Day or whether anyone was prevented from voting. The Houston Chronicle subsequently reported that out of the more than 782 polling locations, only about 20 ran out of paper.

In an assessment of the November election released in January, Tatum detailed proposed actions to improve the operations of elections in Harris County, including obtaining the election tools necessary to track and resolve issues at the polls in real-time — such a system was in place for the May election. Tatum also suggested having a review of the processes for opening polling sites, setting up voting systems and updating their software. As well as hiring additional full-time staff for the elections department and obtaining “sustained and dedicated administrative funding.”

Nadia Hakim, the Harris County elections department spokesperson, did not answer Votebeat’s questions about whether the department has hired additional staff or whether it’s working on its budget needs for next year.

An unclear future

Hakim said the Harris elections office is currently operating normally. “There really is no opportunity to hit pause, so this office will continue to operate business as usual to meet these statutory requirements,” she said, adding that details about what the transition of election duties to the county clerk and tax assessor-collector would look like “remains to be seen.”

Harris County Clerk Teneshia Hudspeth, a Democrat, previously worked under former Republican County Clerk Stan Stanart, who ran elections for the county from 2011 to 2018, before the county created the elections administration department. Hudspeth handled voter outreach for the office and later became chief deputy clerk.

Hudspeth and Harris County Tax Assessor-Collector Ann Harris Bennett, also a Democrat, whose office would take over the duties of updating the county’s voter rolls, declined to comment on the potential transition. Bennett, too, has experience, having been in charge of the voter rolls for the county from 2017 to 2020.

The new law’s author, state Sen. Paul Bettencourt, a Houston-based Republican, told Votebeat that he is certain Hudspeth and Bennett are experienced enough to manage the county’s upcoming elections, but it would be “a mistake to wait” for a court order to begin preparations to transfer the duties “There is no other operational reality right now, unless the courts actually intervene,” he said. “And if not, these people are elected and therefore accountable to the public.”

Meanwhile, the instability could make it hard to retain experienced election workers, Sherbet, the Collin County elections administrator, pointed out.

“It can be very volatile if you don’t have enough experienced, capable people to really take on probably the most complex election not just in the state but in the country,” he said.

Natalia Contreras covers election administration and voting access in Texas for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org