Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

SINTON, Texas — At church last month, Pam Hill’s neighbor approached her after service and asked her if she’d be opening an early voting location in their small town of Odem, just as in previous election years.

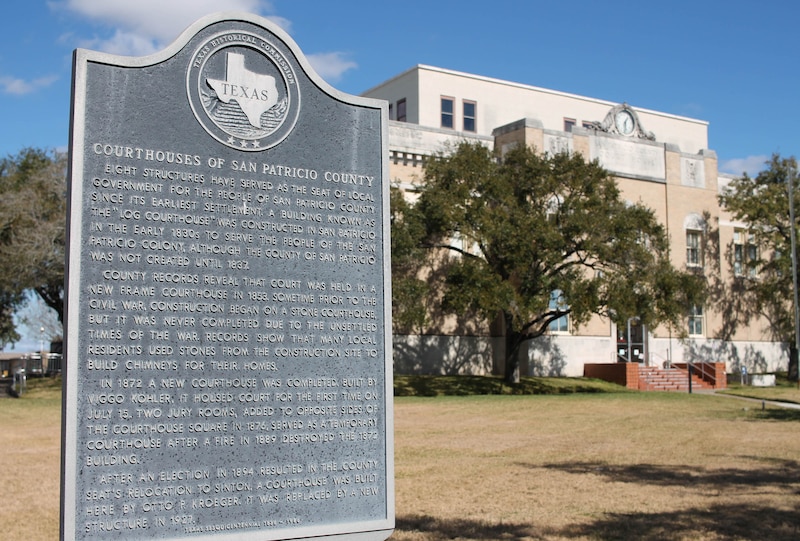

“I can’t. I’m sorry,” answered Hill, who has run elections in San Patricio County for more than two decades. “You’ll either have to wait for Election Day, or you’ll have to come to Sinton.”

Sinton, the South Texas county’s seat, is about 7 miles from Odem, a 10-to-15 minute drive down US Highway 77. But Hill knows some elderly voters in her community won’t, or can’t, make that trek. And she’s worried about it.

“My concern is, what if something happens to them between early voting and Election Day? What if they get sick, or they can’t walk? They won’t be able to go vote,” Hill said.

But Hill has no real choice but to reduce the number of early voting locations in San Patricio County from the eight offered in previous elections to four this year — she’s also shutting down longstanding sites in the small towns of Taft, Ingleside, and Gregory.

Texas lawmakers last year passed a new law requiring all counties, regardless of population, to comply with extended early voting hours at all sites. The law provides very little funding, and Hill’s budget won’t stretch to support the new requirements at all of the county’s previous sites. That means a law intended to give voters in rural areas more opportunities to vote will instead have the opposite effect, as cash-strapped small counties shut down sites when they don’t have the budget to meet the new requirements.

Lawmakers “have no idea what they’re doing to voters in my county,” Hill said. Prior to the new law, small counties had more flexibility. “To me, instead of helping voting, it’s hurting voting. We’re taking their right away” by closing those locations.

What HB 1217 says about extended early voting days and hours

The number of additional early voting days and hours required by House Bill 1217 depends on the election.

For the typically high-turnout March primary and November general election, the main early voting location — usually the county courthouse or the county’s elections administration office — must be open for at least nine hours every weekday except holidays. Early voting sites must also be open on the same days as the main location for at least eight hours each day. In the last week of early voting, the main early voting location must be open for at least 12 hours every weekday and Saturday, and at least six hours on Sunday.

Some of the early voting locations in San Patricio were typically open for less than a handful of days per week, and for seven to eight hours per day. But it was more than nothing.

In the heavily Republican county, less than an hour north of Corpus Christi and home to more than 40,000 registered voters, the money to pay election workers for the additional hours and days are not in the budget. Hill is already digging for money to deal with a different new law, which requires the county to add more polling locations on Election Day. The voting equipment for three required additional locations cost taxpayers more than $80,000, Hill said.

Hill told county leaders about the new requirements and requested more money to pay election workers for the extra hours. County leaders told her they did not want to put an additional burden on the county’s taxpayers and didn’t grant the increase.

The new law allows counties to dip into funds, known as Chapter 19 funds, that the state provides to counties for voter roll maintenance. The amount of money each county receives varies based on how many voters the county adds and removes from the roll, generally 25 cents to 40 cents for each one. The greater the number of registered voters in the county, the more money it can potentially receive.

In smaller counties, however, election officials say the money isn’t enough to pay for extended hours and the workers required to support them. Some counties’ elections departments have seen as little as $900. In some counties where the voter registrar is also the tax assessor-collector, the county clerk’s office, which is in charge of elections, doesn’t have access to the funds at all. Every other year, San Patricio receives about $15,000 from the fund, but the county spends that money paying part-time election workers who perform voter list maintenance duties and for internet access costs, which aren’t going away.

That means there’s no new money to pay for the costs associated with the extended hours now required for early voting sites.

San Patricio’s neighbors, Refugio and Bee counties, typically operate only one early voting location each, which is a common practice in rural counties across the state. For years, San Patricio did the same, before Hill decided to add more in response to requests from voters.

The requests made sense. San Patricio extends more than 55 miles across, and elderly residents prefer voting in their own community. Other residents work in agriculture, steel mills, or the oil and gas industry, and commute daily across surrounding towns and counties for work. More early voting locations made things easier.

The county began to offer one day of early voting in various towns across the county back in the mid-2000s, later adding early voting sites in the towns of Odem, Taft, Mathis, Ingleside, and Gregory for one to three days, depending on the type of election. Hill said anywhere between a handful of voters to a couple hundred would cast ballots at those locations.

“At least they had the opportunity,” Hill said.

“One size does not fit all”

During a legislative hearing in March, state Rep. Valoree Swanson, a Republican who proposed the bill, said her goal was to “make it better for our good people in rural areas.” Swanson, who represents a district in Harris County, the state’s most populous, said voters in rural areas may have to travel long distances to the polls, and the extended hours would give them more time to get there.

The bill passed with bipartisan support and went into effect in September. Swanson did not respond to a request for comment.

Similar legislation to standardize voting hours across counties, ostensibly to increase voting access, has been approved in other states, and similar problems have followed where election officials lack the resources to keep up with the demands.

In 2018, North Carolina legislators approved Senate Bill 325. Not long after, nearly half of the state’s 100 counties had to shut down some early voting sites, in part because of the law. The state did not provide additional funding for the counties to comply.

Experts say research has shown that requiring additional locations or extended hours can negatively impact voters’ experience in jurisdictions that are strapped for funds.

“When legislatures try to manage local governments, it invariably fails because one size does not fit all,” said Bob Stein, a political science professor at Rice University who has done research on when and where people vote, and on early voting. “You’ve got to trust local election officials. The people that run elections in their jurisdictions, who have the data about their own jurisdictions, they should be trusted to make these decisions about the hours and locations they need.”

Some residents who used San Patricio’s early voting sites aren’t happy.

Isabel Martinez, 56, a resident of Odem, has for years voted early in town because “it’s just convenient and I can go just whenever I have some time,” she said. But now, Odem’s early voting location at the Planter’s Grain Co-op won’t be available until Election Day.

Martinez, who works at a fast food restaurant in the evenings, said that whether she votes at all in the March primary, and when, is now up in the air. It’ll depend on her work schedule. She says others in her community may feel the same way.

“People who usually do early voting, if there’s not a place, it’s going to deter them. They’re just not going to do it,” Martinez said. “And on Election Day, if there’s a long line and people can’t wait forever … they’re going to leave and not vote.”

Residents of other counties are facing similar constraints. In West Texas, the new mandate has prevented at least one county from opening additional early voting locations.

Krystal Valentin, the election official in Terry County, a small rural county southwest of Lubbock, told Votebeat that prior to the passage of the new law, she was planning on opening an additional early voting location for residents in the town of Meadow. Many residents in the town, she said, are elderly people who are homebound or unable to drive long distances.

But she’s had to scrap that plan. It’s simply not something the county can afford to do. In order to fulfill the extended hours requirements, the county has already spent an additional $20,000 in order to pay additional workers to fill the shifts at the existing sites. Adding more is out of the question.

“If we could offer an additional location for those voters in Meadow for a day or two, for a couple of hours, we would do it,” Valentin said. “But now because this law says we have to have so many days and so many hours, we can’t afford to do that.”

Has your county closed early voting locations near you due to the new mandate? We want to know how it’s impacting your ability to vote. Email Votebeat reporter Natalia Contreras at ncontreras@votebeat.org

Natalia Contreras covers election administration and voting access for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. She is based in Corpus Christi.