Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

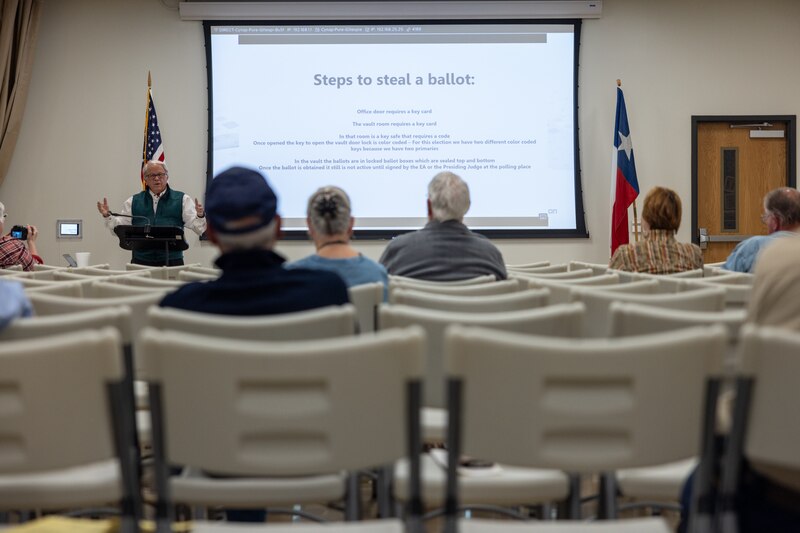

FREDERICKSBURG, Texas — Jim Riley and his team spent weeks preparing for a forum he hoped would remind the public that elections in Gillespie County are “safe, accurate and dependable.”

The new county elections administrator expected more than 50 people. He asked a more experienced election official from a neighboring county to be there, in case he needed help clarifying election laws he’s less familiar with. He planned for a mock election, setting up voting equipment that the audience could use.

But fewer than two dozen people came. And some — county Republicans and local tea party members — walked out before his presentation ended. They’re the same people who Riley believes no longer want him in the job and who have disrupted the way elections are run in the county.

“Yeah, I’m disappointed. But the word will get out. They’ll go out and say that ‘he’s still there. He’s still standing’,” Riley said.

Riley, 76, intends to stay standing, even if it means standing up to the pressure of local right-wing activists who want him to radically change the way Gillespie elections are run. It’s more pushback than he expected when he took the job in August.

“I was just surprised. But I am dealing with it,” Riley said. “I’m not quitting.”

That’s no small commitment, considering Gillespie’s recent history. A little more than a year ago — following years of harassment by local right-wing activists fueled by unsupported claims of election malfeasance and conspiracy theories — the entire elections department in this Hill Country county quit.

Six months into his new role, Riley has signaled that he will not easily bend to the activists’ demands to fix county election problems that don’t exist. Since before he took the job, they have been mounting a pressure campaign to convince local officials to get rid of its electronic election equipment and switch to checking in voters on paper and counting votes by hand.

“If they thought that I was one who would follow along on this, then they were badly misinformed,” Riley said. “I stand by what I said: a hand count will not make elections in Gillespie better.”

A Republican and a semi-retired Presbyterian minister, Riley said when he sees a need, he turns to it and serves.

“In my own personal walk with Jesus, I want to be doing things that would be considered worthwhile. And right now that seems to be this job,” he said.

“Thrown into a hornet’s nest”

Although Riley says he’s got what it takes to endure the big election year ahead of him, some residents worry the county may be at risk of losing yet another election director.

After the entire elections staff quit in the summer of 2022, county officials spent months looking for a new elections director. Riley had been a precinct judge — tasked with supervising polling locations — for the local Republican Party for years, which meant he was familiar with how elections in the county were run. While the job was vacant, he helped manage early voting during the November 2022 midterm election and helped the county clerk in the months that followed. County officials encouraged him to apply for the job; he did so in June.

Meanwhile, some Republicans and activists had been organizing an effort aimed at convincing county executives to ditch electronic voting equipment and instead use volunteers to hand-count ballots.

“We can do this in Gillespie and in the surrounding Hill Country because we’re small enough and we have enough people who want to know the truth,” Angela Smith, a poll watcher and a founder of the Fredericksburg Tea Party, said in July at an event featuring out-of-state election conspiracy theorists promoting hand counting – a method experts say is inaccurate and far more costly.

More than 20,000 registered voters live in Gillespie and about 80% are Republican.

Although county executives dismissed the push to hand count, by the time Riley was appointed to his new position, Republicans had decided they’d hand count in the March primary election – a move state officials had warned would require double the amount of workers and volunteers, of resources and a risk of legal challenges from candidates, but a decision the party was legally allowed to make.

Mo Saiidi, then the chairman of the county’s Republican Party, resigned last fall following his opposition to the party’s decision to hand-count ballots in the primary election.

“Anybody who would have come into that job would have been thrown into a hornet’s nest, to be honest with you,” Saiidi said.

Saiidi was a member of the election commission that appointed Riley. He said the county was left scrambling when former elections administrator Anissa Herrera — who’d run elections there since 2019 — and her staff quit. He’s concerned that it could happen again.

“It’s the same now with Jim there,” Saiidi said. “The same barrages of baseless complaints. This is not healthy, we’ve gotta do something. We need to let them do their jobs.”

“The will of the people”

Texas law allows the political parties to choose the ballot counting method for the primary elections. For the March 5 primary, Republicans in Gillespie have decided they’ll hand count all ballots cast during early voting and on election day.

The party is also taking an additional step to make its election more analog. On election day, the party will ditch electronic poll books, used to check voters in at the polls. Instead, they’ll use printed voter rolls prepared by Riley’s staff.

But during early voting, under Texas law, it’s Riley who gets to decide how to check in voters at the polls during that two-week period. And he has insisted on using the county’s electronic poll book – a system he says is reliable and more efficient in what is typically a high-turnout election.

That’s upset the local activists, who falsely believe election officials can use the electronic poll books to manipulate election results.

For weeks, Republicans and Tea Party members who opposed using the electronic poll books have sent out a ‘call to action’ for residents, asking them to write letters to county Judge Daniel Jones and other county commissioners in hopes they will tell Riley to change his mind.

Over a week ago, Republican precinct chairs Tom Marschall and David Treibs created a 20-minute video about Riley’s decision to “do something other than what the people want,” posting it on social media. In the video, they also suggested that residents ask the county to get rid of the elections administrator position entirely and give those duties to an elected official, such as the county clerk or the tax assessor-collector. Marschall told Votebeat that if Riley were to “abide by the will of the people” he wouldn’t have raised these issues.

“We just want to do it the old fashioned way and do it on paper, and nobody’s going to be able to add 1,000 names to that list when I’m sitting there, guarding it,” Treibs — who could not be reached for comment — said in the video. “Nobody’s gonna mess with that stuff when I’m there. I can guarantee you that.”

In the video, he went on to say that because Riley isn’t elected, “Jim Riley doesn’t answer to anyone and I don’t think that’s a good thing. But we want to try to pressure him and… be nice of course.”

Election administrators are nonpartisan positions appointed by an election commission made up of the county clerk, the tax assessor-collector, the chairs of the local political parties and the county judge.

“Right now, I’m experiencing a mess”

So far, Riley hasn’t budged on the demands from the activists. Instead, he’s been focused on rebuilding trust and learning as much about elections as possible. In January, he attended a conference and training for Texas election administrators, networking with other election directors across the state and with staff at the Texas Secretary of State’s Office.

He says he often calls election directors from neighboring counties for advice and doesn’t shy away from admitting that he still has a lot to learn. He takes tips and examples on what he can do to rebuild trust in local elections. The lightly attended public forum was one such attempt.

With the pressure of learning the ins and outs of elections, in a state where laws are often changing, and in a county where election officials have in the past found the job to be too much, some election administrators say support from county commissioners — who control the county’s budget and resources allocated for the elections department — goes a long way.

In Llano County, about 30 miles north of Gillespie, Andrea Wilson has been the elections administrator for over a year. She quickly learned that the job required her to become an election law expert, a record-keeping expert, a logistical manager, a trainer for election workers, a budget strategist and an office administrator to keep track of supplies, among other duties.

And the hours of work are extensive. Wilson’s kept track: The two weeks of early voting now covers 115 hours that election administration staff must be present in the office and an additional 17-plus hours on election day, she said.

“With all of that resting on your shoulders, could you then imagine having to fight with your county commissioners for the staff necessary to support that mission or a budget to pay for all the necessary supplies?” Wilson said. “Or even worse is adding to your already overflowing plate the spread of misinformation.”

Without support, Wilson said she wouldn’t have lasted a year on the job in Llano. She said it should be “the standard” for all counties to provide that kind of support to their elections departments.

When Herrera, the previous elections administrator in Gillespie quit, in her resignation letter she told county officials that “the threats against election officials and my election staff, dangerous misinformation, lack of full-time personnel for the elections office, unpaid compensation,” had in part made the job “unsustainable.”

Her staff was made up of one more full-time employee and a part-time employee. She’d asked county officials for two more full-time employees but the county only approved one and it’s unclear whether it was filled or whether the county plans to allocate funding to pay for additional workers in the future. Gillespie County Judge Daniel Jones did not respond to Votebeat’s multiple requests for comment about how the county plans to support its elections department and to help retain election staff in Gillespie.

The number of people working in the Gillespie elections department remains the same: two full-time employees, including Riley, and one part-time employee.

Although at times he admits the pressures of the job can be overwhelming and frustrating, Riley told Votebeat he is confident he has the support of Jones and other county commissioners. And he relies on his faith often to keep at it, any time he’s discouraged, he said. But he’s committed to running elections in the county as long as he can.

“In the midst of everything that is just kicking you in the butt. If you spend a little time in the word, spend time in prayer and you seek it through Jesus. You’ll be amazed at what he allows you to experience,” Riley said. “So, right now, I’m experiencing a mess, but I haven’t felt alone in it at all.”

Natalia Contreras covers election administration and voting access for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org.