Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Texas’ free newsletter here.

A long-running conservative push to get rid of countywide polling places is winning growing interest from state lawmakers, as well as a spot on the state Republican party’s list of legislative priorities for next year.

But election officials are warning that if legislators scrap the state’s countywide voting program, they will struggle to pull off the changes that would be required — beginning with increasing their numbers of polling places. That means paying for hard-to-find additional locations, recruiting and paying workers to staff them, and obtaining more voting equipment.

Election officials also worry that confused voters could be disenfranchised by the shift.

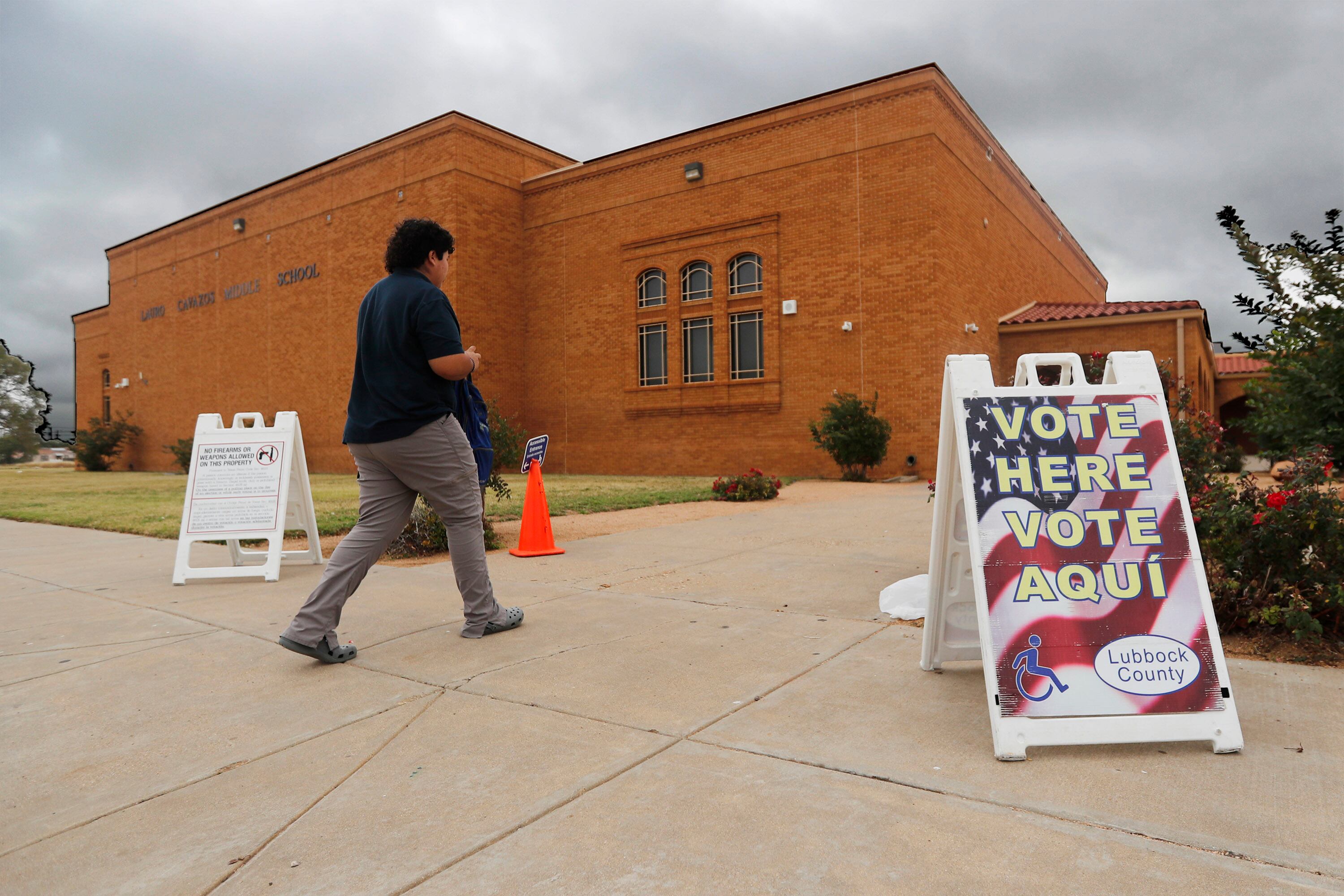

Currently, 96 counties allow voters to cast ballots anywhere in their county on election day, according to the Texas Secretary of State’s Office. The list includes counties in every part of the state, collectively encompassing roughly 14.9 million, or 83%, of the state’s registered voters.

Banning the program would force those voters to again cast their ballots only at their assigned precinct, after years of allowing them to go to any voting site in the county.

Voters who mistakenly go to the wrong site would be offered a provisional ballot, said Roxzine Stinson, the Lubbock County elections administrator, and if they aren’t able to instead go to their assigned precinct, “then that’s their only option. And voting provisionally, that’s no guarantee that that vote is going to count, because they’d be voting outside of their assigned polling location.”

Critics of countywide voting — who testified before a Senate State Affairs Committee hearing last month — allege without evidence that it makes elections less secure because it allows people “to double or triple vote.” Countywide voting relies on using electronic voting equipment, and critics say that election officials manipulate such equipment to change votes and sway election outcomes, but they haven’t shown evidence to back up those claims, and experts say they are false.

Local election officials who have overseen countywide voting for years say they have yet to see any such fraud occur. State election officials, too, have for years deemed countywide voting successful and say it is well-liked by voters who use it.

Election administrators say they are already struggling to comply with legislation passed last year requiring them to increase the number of polling locations they operate and to increase the number of hours and days of early voting. Some have had trouble finding public buildings that comply with access requirements for voting sites. In other areas, where funding can’t stretch to pay for the additional required hours, election officials have had to shut down early voting sites, resulting in less access for voters.

In Lubbock County, Stinson estimates eliminating countywide voting will require spending at least $300,000 more on elections, and “that’s just a start. Because it’ll take more workers, more training and more equipment.”

Eliminating countywide voting would require more sites, workers

Texas is among 18 states offering countywide voting or vote centers, including Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, and Tennessee.

Created in 2003 by an election official in Larimer County, Colorado, the vote center model was designed to meet accessibility requirements stipulated in the Help America Vote Act of 2002. The federal law set aside funds to address issues with outdated voting technology and voting access problems after the 2000 presidential election. The requirements were costly, and some counties would have had to provide additional voting equipment at hundreds of locations. The vote center model allowed counties to offer fewer locations, but gave voters access to cast their ballots at all of them. State officials must approve counties’ participation in the program.

Texas began offering the option in 2006, after a Republican state representative introduced a bill setting up a pilot program. The bill won bipartisan support; participating counties were required to have electronic poll books and other voter registration management tools necessary to ensure voters only cast a single ballot.

Lubbock County, a Republican stronghold, was the first to sign up. County commissioners and community leaders were involved in selecting the vote center locations and ensuring that they were easily accessible to all voters, Stinson said, and residents have become accustomed to voting wherever is most convenient for them.

Stinson said she and her staff already have trouble recruiting enough election workers for the county’s 40-plus vote centers. She’s not certain whether she’d be able to recruit the minimum of three election workers per location for the additional 40 locations she’d need to open if the county is required to return to precinct voting.

“If we’re struggling now, what makes you think we’re going to be able to just open up that many more locations and that we’re going to get that many more workers?” Stinson said.

Election officials also note that the countywide system provides more options for voters if something goes wrong on the day of an election.

For example, during this year’s primary runoff election in May, a storm forced at least a dozen polling locations in Harris County to shut down after losing power. And in North Texas, at least 76 polling places in four counties closed after the weather left hundreds of thousands of residents without power.

Counties in those affected areas use vote centers. Although some polling sites closed, voters in those areas were still able to cast a ballot at open locations across their counties.

Shannon Lackey, the Randall County elections administrator, said that if those counties were precinct-based, “they would potentially have to turn away voters, there would be no way for them to cast a ballot.”

The same alternative is useful, she pointed out, if a water main breaks at a particular location, if equipment goes down, or if paper jams.

For Texans with disabilities, voting at a precinct polling location, which would typically be located within a neighborhood, isn’t always the most accessible option, said Chase Bearden, deputy executive director of the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities.

“Sometimes streets and sidewalks are torn up and aren’t paved. If you don’t have a vehicle, public transportation is necessary and some neighborhood locations may not be near a bus stop,” Bearden said. “A lot of people with disabilities, once they find a location that is accessible and meets their needs, they continue going back to it. That wasn’t always the case with precinct-based locations.”

Critics make unsupported allegations about vulnerabilities

The program’s most vocal critics have for years falsely claimed the use of electronic voting equipment in counties that participate in the program has led to malfeasance by election officials. Some Republican lawmakers have paid attention.

Last year, Senate Bill 990, authored by North Texas Republican state Sen. Bob Hall, aimed to eliminate the countywide voting program and require residents to vote at their assigned precinct. The bill, which passed the Senate but did not advance in the House, would have still permitted use of vote centers during early voting.

At the time Hall alleged countywide voting creates “unexplainable inconsistencies,” though he didn’t supply details or evidence. He said his measure would prevent inaccurate vote totals and that it would also prevent people from voting more than once. During Senate floor debates, Democrats who opposed the bill pressed him for evidence that countywide polling had allowed voters to cast ballots at more than one location. He didn’t provide any.

At the Senate State Affairs Committee hearing last month, chair Bryan Hughes, a Republican who has championed some of the state’s most restrictive voting laws, had invited testimony from Beth Biesel, a Dallas County Republican poll watcher and proponent of hand-counting ballots. Experts have said time and time again that hand counting is not accurate, and is far more costly than using voting machines to tabulate results.

At the hearing, Biesel falsely claimed voting machines were connected to the internet. She also falsely claimed that the program had contributed to a recent problem where people could use a series of public records requests to pierce ballot secrecy and figure out how certain people voted. In fact, that problem stems from Texas’ push to make almost all election records public, allowing researchers, in some limited instances, to cross-reference different public records and find a specific voter’s ballot image. (The state recently moved to eliminate that possibility, following reporting by Votebeat and The Texas Tribune.) Biesel proposed that lawmakers eliminate countywide voting, get rid of electronic voting equipment, have everyone vote at their assigned precinct, and hand-count ballots.

The hearing witness list signals the preferred approach of committee leadership, said Brandon Rottinghaus, a professor of political science at the University of Houston.

“Specifically, you’ll see allies are going to get softball questions,” Rottinghaus said. “Putative enemies often become strawman arguments in favor of whatever lawmakers’ preferred point is.”

Some lawmakers who heard Beisel’s concerns then turned to one official with the Secretary of State’s Office for clarity. “If I’m voting for Mickey Mouse for President, can that be manipulated?” state Sen. Charles Perry, a Republican of West Texas, asked.

Elections division director Christina Adkins promised that no voting machines in the state are connected to the internet. “We do not allow wireless connectivity on our voting devices, we test that in the certification process,” said Adkins, who was also invited by Hughes to testify.

She added that, although concerns over ballot secrecy are valid, those problems are not exclusive to countywide voting. “It extends to early voting. It extends to voting by mail,” Adkins said.

Adkins added that countywide voting could be improved by finding more efficient ways to reconcile election results in order to make post-election auditing easier for election officials, and lawmakers at the hearing agreed. However, it’s too soon to tell the kind of legislation they’ll propose. Lawmakers are expected to begin filing legislation after the November presidential election.

Natalia Contreras covers election administration and voting access for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org