Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Wisconsin’s free newsletter here.

Voters using Wisconsin’s newly legalized drop boxes may return only their own ballots, except in special cases, according to new guidance from the Wisconsin Elections Commission. That means even a voter dropping off a spouse’s ballot along with their own could be considered as having cast a ballot improperly.

The rule could be difficult for municipal clerks to enforce. But it leaves an opening for potential challenges from conservative election activists, who are already preparing to act on suspicions that Democratic voters will abuse the boxes to commit fraud. Allegations of drop box misuse could also spur legal challenges to election results, experts say.

In the run-up to this year’s elections, local officials are dealing with heavy scrutiny from election observers seeking to challenge absentee ballots, and Republicans have sought to increase the number of people monitoring drop boxes. Republican U.S. Senate candidate Eric Hovde last week called for 24-hour drop box monitoring in Madison, The Washington Post reported.

Those calls came quickly after a Wisconsin Supreme Court majority on July 5 overturned a 2022 decision that banned drop boxes. Since the decision, clerks in cities like Madison, Milwaukee and other municipalities around the state have stated their intent to use drop boxes in the August primary.

Drop boxes became one of the most politicized election issues in Wisconsin after the 2020 presidential contest, leading to extensive misinformation, false allegations of widespread fraud, and “2,000 Mules,” a purported documentary about drop box misuse that has been roundly debunked. Their return in Wisconsin promises to revive the suspicions that fed those claims.

“People who don’t believe that the system has integrity are looking for places to prove that, and the drop box just becomes an easy place to go, because it’s in public, and there are lots of voters interacting with those boxes as they deposit ballots,” said UW-Madison political science professor Barry Burden, the founding director of the university’s Elections Research Center. “And so it’s a place where their suspicions can be tested.”

Already, on social media channels prominently featuring election conspiracy theorists, people are making plans to monitor drop boxes.

One person in a Telegram group called for people to “Sit by those boxes like flies on shit.”

Another suggested what could be more menacing behavior, calling for drop box observers to follow voters home, “Make a note of their address then post it on Telegram.”

Even a perceived misuse of a drop box could be used to fuel concerns about election integrity, UW-Madison Law School associate professor Robert Yablon said.

“It may mean that you have more observers that are going to camp out at drop boxes looking for something that they think is wrong, whether or not it is, and having a viral moment,” he said. “There often may well be innocent explanations, but nevertheless, the appearance will be something questionable enough for them to run with.”

The last time drop boxes were in use, there wasn’t a rule or guidance explicitly addressing whether voters had to return only their own ballots to drop boxes. When the Wisconsin Supreme Court banned them in 2022 following a challenge from conservatives, it said voters with absentee ballots had to mail them or deliver them in person to the clerk, but didn’t rule on whether a voter could mail other people’s ballots.

When the state Supreme Court, now with a liberal majority, overturned the drop box ban on July 5, it didn’t address whether people could return ballots besides their own to a drop box. But the commission stepped in with its guidance, saying voters can return only their own ballots unless they’re helping somebody who’s disabled or hospitalized.

Additionally, the guidance clarifies the court decision doesn’t require drop boxes to be staffed or require clerks to “ask any questions” of a voter returning a ballot to a drop box.

People can watch drop boxes, as long as they don’t interfere with voting, the guidance says, and clerks should contact law enforcement if people impede the use of a drop box.

‘Vigilantes’ could get involved in monitoring drop boxes

Besides Wisconsin, 27 states explicitly allow drop boxes, while another six states have jurisdictions that use them.

States differ in their rules on who can return voters’ absentee ballots to a drop box or a clerk. In Georgia, which has drop boxes, voters’ absentee ballots can be returned by their family members, household members, or caregivers. In Alabama, though, voters can return only their own ballots.

In Wisconsin, Burden said, the new WEC guidance draws “a brighter line” than the courts did on the issue of who can return a ballot. “So it might give some justification for these kinds of vigilantes who want to watch the drop boxes and look for wrongdoing.”

Burden cautioned, though, that there could be ambiguous situations where these people might incorrectly “jump to conclusions.”

For example, a voter could be putting three ballots into a drop box, two of them completed by their disabled parents, which would be allowed, he said. But if an election observer captured that on video, such a moment could be misinterpreted, or deliberately misused, to spread suspicions of improper voting.

“It gets very easy for a misunderstanding to spin out of control,” Burden said, “and so it would be much better for election officials or courts — people who actually know what they’re doing — to be on top of this, rather than allow rogue individuals to inject themselves into the process.”

Burden warned that such vigilante behavior could escalate to a form of voter intimidation, as in Arizona in 2022, where a group of people wearing masks and carrying guns stood close to drop boxes until a judge ordered them to stand farther away.

Challenges to drop boxes could take many forms

In Shorewood Hills, a 2,100-person village surrounded by Madison, village Clerk Julie Fitzgerald unlocked the village drop box the day the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled 4-3 that they were legal.

Fitzgerald said having drop boxes available again for ballots is especially convenient because the village box is also used by residents to drop off their utility payments. When drop boxes were banned for voting purposes, Fitzgerald had to close them off during elections, requiring residents to return utility payments elsewhere.

Neither the court’s ruling nor the election commission’s guidance requires drop boxes to be staffed. Before the commission issued its guidance, Fitzgerald said she hoped it wouldn’t put the onus on clerks to monitor drop boxes.

But clerks can still come under scrutiny if a voter returns multiple ballots. And they would face pressure to do something about it to preserve the integrity of the vote count.

“As a statutory matter, the rules concerning return of absentee ballots are mandatory. Improperly cast absentee votes are not to be counted,” said Rick Esenberg, president of the conservative law firm Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, which filed the lawsuit that led to the 2022 drop box ban.

There are a few different ways to handle a situation like that, Esenberg said.

One option is a drawdown: That’s when election officials withdraw randomly selected ballots because of a numerical discrepancy and exclude them from the count. State law outlines a drawdown as a possible remedy when, during canvassing, the number of tabulated ballots is greater than the number of recorded voters. The idea is that if they can’t determine exactly which ballots should be invalidated, they might at least be able to determine the quantity of those ballots, and randomly select that quantity to exclude from the count.

State law and the election commission’s manual don’t stipulate doing a drawdown for improperly returned absentee ballots, but plaintiffs could request such a remedy in a lawsuit.

Other remedies can be considered, Esenberg added, pointing to a North Carolina case where the state ordered a new election after the Republican candidate’s campaign was accused of ballot tampering.

Post-election challenges have limitations, however, Esenberg said.

After the 2020 election, the Wisconsin Supreme Court rejected a challenge by then-President Donald Trump that called for drawing down 220,000 votes from Dane and Milwaukee counties. The ruling said it was “unreasonable” for Trump to challenge the ballots after the election on the basis of laws and procedures that were in place well before the election.

Referring in part to that case, Yablon said, “Courts in Wisconsin and elsewhere do tend to hesitate before throwing out the votes of eligible voters.”

If the returned ballots are otherwise proper, he said, “the courts are going to be very reluctant to disenfranchise someone based on a deficiency in just how it was returned.”

Challenges to current drop box rules could also come from the other direction, in favor of expanding return options, Yablon said.

Groups that want to loosen the current guidance could ask the commission or a court permission for them to collect and return multiple ballots, arguing that the Supreme Court’s latest ruling represents a broader preference for expanding return options, he said.

Safeguards against fraud are in place for ballots left in drop boxes

It’s possible under the current rules that an otherwise legitimate ballot can be returned improperly, leaving clerks or challengers to find a way to resolve that issue.

But election officials have safeguards in place to protect against the possibility of widespread fraud through drop boxes, like somebody filling out and returning multiple ballots to a drop box under fake names or in the name of somebody who has already voted.

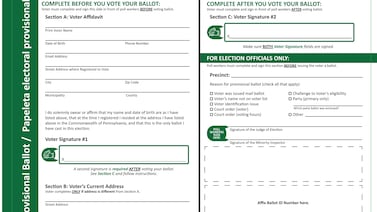

Wisconsin clerks process absentee ballots from drop boxes just as they do any other absentee vote, including those sent through the mail or dropped off in person. With narrow exceptions for military voters, election officials send absentee ballots only to Wisconsinites who have requested one and are confirmed to have registered to vote with a valid ID.

Before opening the ballot envelopes deposited in a drop box, election officials verify they have witness and voter signatures and a witness address. Then they open the envelope, verify that the person casting the ballot was qualified to vote and that they hadn’t already voted in the election, and record them on the poll books as having returned their absentee ballot. Only then would they tabulate the vote.

In its guidance, the commission also issued best security practices for drop boxes, including making sure drop boxes are in a well-lit area, that they have locks or seals to secure ballots, and that they can’t be moved or tampered with.

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.