Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Wisconsin’s free newsletter here.

Denise Jess walked into a Madison polling place on Saturday to vote early in person, and encountered a familiar barrier: an absentee ballot envelope with a blank space for writing in her name, birthdate, and address.

Jess, who is blind, chuckled along with her wife, who accompanied her to the polls. Who was going to do all that writing?

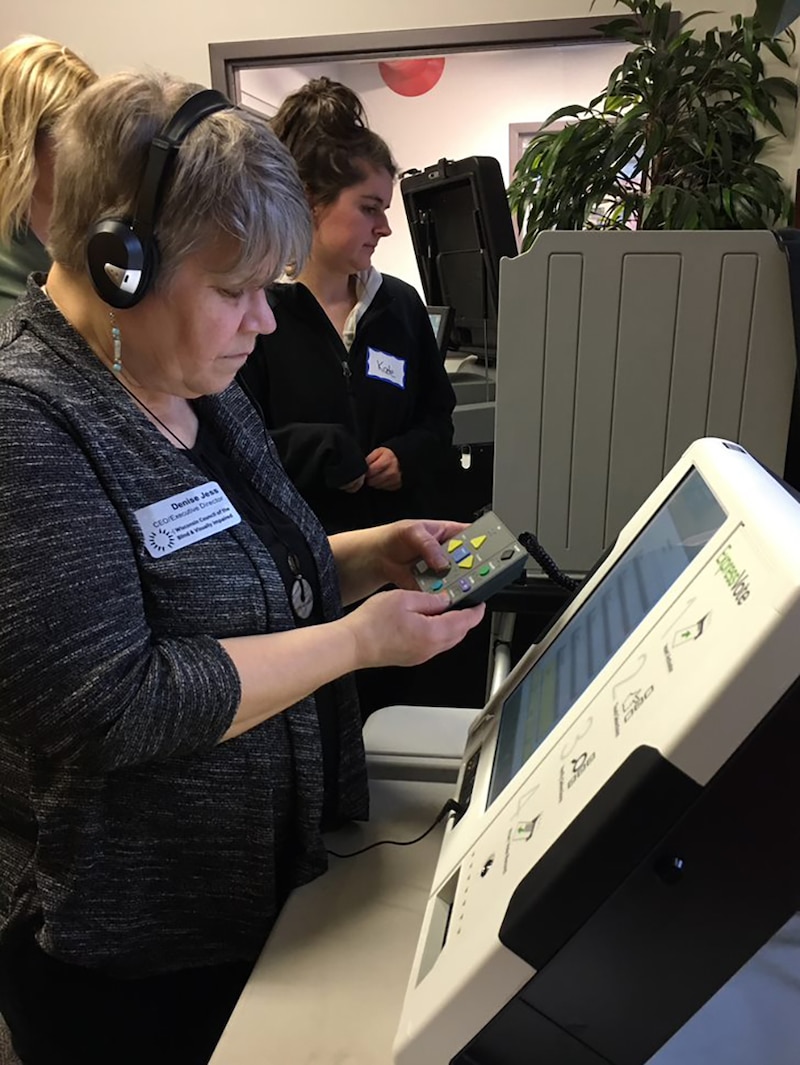

A poll worker quickly offered help, reminding Jess that she had the right to assistance. Jess, who is executive director of the Wisconsin Council of the Blind & Visually Impaired, knew she had those rights. But the moment still bothered her.

“It’s just a bummer,” she said, comparing voting with other tasks she performs independently, like identifying birds by ear, paying bills online, posting on social media, and grocery shopping. Voting is a constitutional right in Wisconsin and yet, she said, it remains far less accessible.

Other industries that have prioritized accessibility because it benefits their bottom line, she said, but voting systems were not originally designed with accessibility in mind.

“We’re making strides,” she said, “but it’s still always, always about retrofitting and trying to catch up.”

Jess’s experience illustrates a persistent tension in election policy: how to ensure both ballot security and accessibility for all voters. Electronic absentee voting is particularly nettlesome. Disability rights advocates have pushed for this option as a way for people with vision or other disabilities to vote independently, and in private, from home. But cybersecurity experts warn that current technology cannot guarantee that ballots returned electronically will be safe from hacking or manipulation.

Over a dozen other states provide fully electronic absentee voting for people with disabilities. In those states, voters with disabilities can receive a ballot electronically, mark it using a screen reader, and return it electronically — similar to signing and returning a document electronically. Wisconsin isn’t one of them. Here, voters with disabilities must cast their votes on a paper ballot, or on an accessible voting machine at a polling place that prints out a paper ballot.

That means that voters who are blind, visually impaired or unable to write must often rely on others to complete their ballots — undermining ballot secrecy, which is also constitutionally protected. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when many disabled voters were reluctant to visit the polls in person, Wisconsin’s rules presented an even bigger barrier.

Last year, four voters with disabilities, along with Disability Rights Wisconsin and the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin, filed a lawsuit seeking access to electronic absentee voting. A lower court initially granted some voters that option, but an appeals court paused and eventually reversed that order. The case is now before the Dane County Circuit Court.

Beyond the roughly dozen states that offer fully electronic voting, a few others, including Vermont, Michigan, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, allow voters with disabilities to fill out ballots electronically, but they have to print out the ballots and return them by mail, drop box, or in person. Verified Voting, a nonpartisan election technology group, promotes this option as a step forward for states wary of fully electronic voting.

That wouldn’t solve the issue for everyone, though. Jess pointed out that many blind voters don’t own printers, meaning they’d still face accessibility hurdles.

Security concerns haven’t been resolved

At a time of heightened concern over election security and integrity, some technology experts say fully electronic voting is still not ready to be used widely.

Between August 2021 and September 2022, the University of California, Berkeley, hosted a working group of election, technology, and cybersecurity experts to discuss the feasibility of creating standards to enable safe and secure electronic marking and return technologies. The group found that widespread adoption of electronic return would require technologies that don’t currently exist or haven’t been tested.

A 2024 report by several federal agencies, including the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Election Assistance Commission, found that sending digital copies of ballots to voters is safe, and that filling them out electronically is somewhat safe, but that returning them electronically adds significant security risks.

“Sheer force of will doesn’t suffice to solve this problem,” said Mark Lindeman, the policy and strategy director at Verified Voting. “There needs to be extensive technical innovations that we can’t just dial up.”

Lindeman said threats from electronic ballot return include the possibility that somebody hacks into the system and changes votes. One potential safeguard — having voters verify that their selections were received and counted correctly — remains unproven at scale, the UC-Berkeley working group said.

“That’s the fundamental technical tragedy at this stage of the game,” Lindeman said. “Paper ballots are obviously inconvenient for many voters. They pose real obstacles to voting, but we haven’t found a technical alternative to paper ballots that solves all the problems.”

Denise Jess chooses ‘path of least pain’

In Wisconsin, Jess chooses between three imperfect voting options.

She can vote on Election Day in her polling place, whose layout she has memorized, though it can get too busy for her comfort. She can vote using an accessible machine but still has to hand-sign the poll book, something she typically does with the assistance of a poll worker and a signature guide, a small plastic card with rectangular cutout that frames the area where she has to sign.

Alternatively, she can vote absentee in person during the early voting period, but then she has to receive help with paperwork and navigating an unfamiliar polling place.

Or she can fill out an application online and vote by mail, which she avoids because she can’t fill out a paper ballot without assistance.

“It’s kind of like, what’s the path of least pain?” she said.

For this Wisconsin Supreme Court election, given the potential for bad weather, she opted for early in-person voting at the Hawthorne Public Library, which isn’t her regular polling place.

“There’s enough consistency here at Hawthorne, but still there are surprises,” she said, sitting at a table at the library on Madison’s east side. “Even the simple navigation of going to the table to get the envelope, getting in line. They’re queuing people to wait behind the blue tape, which, of course, I can’t see.”

She could opt for more hands-on help from poll workers to speed up the process, but she said she sees her voting trips as a chance to learn more about the potential barriers for people with disabilities.

Some voters who are newer to vision loss or have more severe barriers can quickly become demoralized by the extra energy they need to put into casting a ballot, especially if poll workers aren’t trained or ready to help, she said.

“We’ve had voters say, ‘I’m not going back. I’m just not doing that again, doing that to myself,’ she said. “So then we lose a voter.”

If electronic voting were available, Jess said, she would do it a lot more often than voting in person because she wouldn’t have to depend on transportation or the weather.

“It would just be absolutely liberating,” she said. “I might still vote in-person at my polling place periodically, because I like my poll workers, and I always like to visit with them and give them kudos. But it would surely ease some stress.”

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.