Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S.

This news analysis was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

For the last several weeks, election watchdogs and many other people have been abuzz over the rather strange actions of the Georgia State Elections Board.

The most recent one: The board decided last week that every precinct must now complete a hand count of ballot totals, to make sure that they match the tallies from the machine counts before the county can certify the election results. While some initially interpreted the rule to mean hand-counting all votes, the rule requires only that the number of ballots be tallied. That will take less time than a full hand count of votes, but it doesn’t mean it won’t cause problems or delays, especially since local election officials will have to add a step to their processes, with just weeks to go before the election.

State officials didn’t want this.

“Misguided efforts to impose new procedures like hand counting ballots at polling locations make it likely that Georgians will not know the results on Election Night,” Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, warned in August, before the board voted to approve the change. “Georgia law already has secure chain of custody protocols for handling ballots, and efforts to change these laws by unelected bureaucrats on the eve of the election introduces the opportunity for error, lost or stolen ballots, and fraud.”

The state attorney general, Christopher Carr, had advised the board that the hand-counting proposal was likely unlawful, because the legislature had not empowered the board to create such a requirement. Like a majority of the state elections board, including every member who supported this change, Raffensperger and Carr are both Republicans.

All of this is likely to spark more litigation. The Georgia Democratic Party and the Democratic National Committee already sued the state elections board late last month over new rules governing how local officials finalize vote totals, contending they would cause “chaos” in the upcoming election. A hearing is scheduled in Fulton County in early October.

So that you can understand the implications of the new rule requiring the hand-tally of ballots, let’s start by explaining how voting works in Georgia: People voting in person select their candidates on a touchscreen voting machine, which prints out a paper ballot, like a receipt from a cash register. That paper ballot includes a list of the voter’s choices and a QR code that can be read by a separate tabulator machine. The voter takes their ballot printout and places it in the tabulator, which scans the code and tallies the votes.

Under the new rules, there are more steps. At the end of voting on election night, after removing the ballots from the scanner, three poll workers have to count them, by hand. When all three agree on the total number of ballots they have, the rules require them to document that number and sign off on it. Then they have to check that number against the ballot totals recorded on the voting machines. Any inconsistencies must be documented, and the person in charge of the precinct is responsible for determining how the error occurred.

In isolation, the requirements in Georgia seem harmless: Why should it be a big deal to require three people to count some paper, and agree on the number they’ve counted, to make sure that no ballots were counted or excluded improperly?

Actually, there are a lot of reasons.

First, changing the rules this close to Go Time is inherently harmful: Poll workers have been recruited, many have been trained, and the handbooks that dictate how they do their jobs have been printed. Late changes mean that poll workers are deviating from the process they understand, and officials are scrambling to revise these procedures at the last minute. Given the number of ballots that will be cast in Georgia —around 5 million were cast in the 2020 general election — this is unlikely to go perfectly in the hundreds of precincts across the state.

And Raffensperger is right: This is a huge change to Georgia’s “chain of custody” requirements for ballots. It introduces a lot more fingers to the process. It also means more opportunity for error, and more time before results can be reported.

“In smaller precincts, these delays should be minimal — there being not that many ballots cast. For larger precincts, the delays may be more substantial,” writes Anna Bower at Lawfare. “If larger precincts opt to hand count ballots on election night, then reporting of results could be delayed by several hours. A few hours could stretch into a day or two if a precinct puts off hand counting until the next day, as the rule allows.”

It’s during such delays, as we saw in 2020, that purveyors of election misinformation go to work, planting false notions about ballot dumping, poll worker misconduct, or fraud to explain pauses or anomalies in reported results and subsequent swings in vote totals.

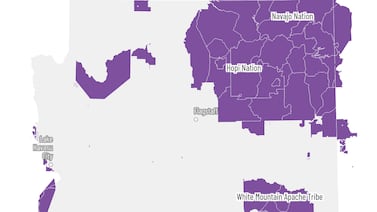

Arizona introduced its own hand-count requirement — though it did so months ago, giving election officials more time to adapt procedures. The Arizona rule requires counties to hand-count the number of ballot envelopes dropped off at polling centers on Election Day before any ballots are tabulated. It applies only to ballots dropped off, not ballots cast at the centers themselves.

Still, it’s likely to cause delays. After the July primary, Maricopa elections spokesperson Jennifer Liewer said the process added about 30 minutes to the reporting time for the county’s results. She said the delay is likely to be longer in the general election, when hundreds of thousands of ballots are likely to be dropped off.

Georgia is one of several states considering last-minute changes in the way elections are administered. In North Carolina, litigation around whether students could use digital IDs to vote went down to the last minute. In Pennsylvania, long-running court disputes have left in limbo the rules over whether mail ballots with dating errors should be counted and how voters can overcome their mistakes. And in Nebraska, Republicans mounted an unsuccessful last-ditch effort to change the way the state’s Electoral College votes are apportioned in an attempt to help Donald Trump — a change that could have tipped the election outcome.

The vast majority of counties will pull off their elections with no issue. But last-minute changes in procedures increase the likelihood of mistakes that — even if they don’t prevent certification — will add confusion and delays in the reporting of results.

And, as we have all seen, confusion and delays in the results have led candidates (and voters) to make harmful false claims that shape people’s perceptions of the election for years. We will certainly see that this year.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.